These textual and visual essays are meant to bring information about collectors, collections, and hidden hands to light

A short film by Michelle Smith, Assistant Professor at McGill University, and a Red River Michif educator and filmmaker born and raised in St. James, Manitoba. The film records a visit to the collections of Métis and Indigenous beadwork at the McCord Stewart Museum in November 2023.

The McCord Stewart Museum is fully committed to decolonizing its practices, including those relating the Collections Management, and to amplifying access to Indigenous cultural belongings under its care. You can explore more on the website:

And view Métis belongings in our online database:

Frances Simpson (1812-53)

…I must here observe, that a Canoe voyage is not one which an English Lady would take for pleasure; and though I have gone through it very well, there are many little inconveniences to be met with, not altogether pleasing…

Diary of Frances Simpson, June 26th, 1830

Biography

Written by Mallory Novicoff

View Essay

Frances Ramsay Simpson was born in 1812 in London as the second child and eldest daughter of merchant Geddes Mackenzie Simpson (unknown-1848) and Frances Hume Hawkins (October 1783-September 1862). Mackenzie Simpson and Hume Hawkins had 15 children, two of whom died young. Geddes Mackenzie Simpson’s loss of an estate in British Guiana (now Guyana), on which there were 209 enslaved people when Simpson attempted to claim a reimbursement in 1836, and having gone bankrupt in 1820 alongside his partner James Webster, stretched the resources of the large family quite thin.1 Frances Simpson was born while they lived at 73 Great Tower Street, London, and around 1816, the growing family moved to New Grove House, Bromley St. Leonard, in a less central part of the city. Though modest, the New Grove House had a garden for the family to enjoy the outdoors and indulge in their passion for gardening.

While growing up, Simpson was directly exposed to gardening and likely botany in some capacity during her time in London. A friend of the Simpsons, Letitia MacTavish Hargrave (c. 1813-1854), the Scottish-born wife of Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) trader James Hargrave, wrote in 1840 when visiting Frances Simpson’s childhood home in London that they had a “beautiful garden” that “mother and daughter enlarged on its loveliness,” referring to Frances’s mother and Isobel Finlayson, Frances’s sister.2 Hume Hawkins spoke of her love for gardening and how if she were to have had more money, she would “beautify her little shrubbery” but appreciated what she did have and her husband’s generosity.3 She then presented Hargrave with their only ‘China rose’ in the garden and a bunch of lilacs, representing all the flowers in bloom.4 This interaction shows that Frances Simpson would have had direct access to a garden in her London home and that her mother was passionate about the beauty and the cultivation of popular garden flora.

In addition, if Simpson had a formal education, her curricula would likely have included some botany and floral aesthetics.5 British society viewed botanical sciences and plant collecting as a suitable and “fashionable science” for women from the Regency era into the mid-Victorian period.6 From 1760-1830, the simplicity of the Linnaean taxonomic system led botany to thrive as a popular science in England, appearing in an expanse of media.7 Botany found its way into school curricula, and many books were written for both formal and informal use, whether that be in families or school.8 By the early nineteenth century, there were also several teaching resources like books and lectures specifically aimed at a female audience.9

Changes: The Arrival of George Simpson

The will of Geddes Mackenzie Simpson, dated 1849, provides further insight into the Simpson family’s condition and finances. Mackenzie Simpson explained that having to “rear and educate” a large family consisting of eight daughters and five sons had put a financial strain on the family and led his estate to be quite limited, consisting chiefly of two life insurance policies with the Equitable and the York.10 Mackenzie Simpson’s bankruptcy in 1820 led him to rely on relatives for financial support, including his nephew George Simpson (c. 1792- 1860), the Governor of the Northern Department of the HBC in Rupert’s Land, who would eventually be married to Frances.11 Mackenzie Simpson named his nephew as an executor and a recipient of the profits from many of his investments due to George Simpson’s past financial support of the Mackenzie Simpson family. This connection could be one of the reasons Frances Simpson married her cousin, to retain positive ties with the family’s benefactor.

George Simpson already had an unofficial “country wife” in Rupert’s Land, Margaret Taylor, who was Métis (her mother was Cree and her father English). Simpson and Taylor’s relationship was an example of “marriage à la façon du pays,” or common-law, non-ceremonial marriage often between French traders, British HBC officers, and Indigenous women. Sylvia Van Kirk suggested that these marriages were “the basis for a fur trade society” where the women would assist with creating trading ties and assure the survival and care of the officers and the fur traders who wintered at posts around Canada.12 However, officers and traders moved frequently from post to post, often abandoning their country wives and children. George Simpson had previously argued that country wives would provide alliances and were the “best security for the goodwill of the Natives.”13 He and Taylor had several sons, but Simpson relinquished much of his responsibilities as a father.14 He left Taylor and their sons with the impression that he would return to them as their husband and father in Rupert’s Land, but on February 24, 1830, George and Frances Simpson were officially married in England.15

Across the Atlantic: Liverpool to Lachine

George Simpson led his new British wife from Liverpool to Rupert’s Land, the large territory in western Canada over which the HBC claimed control until 1870. Frances Simpson kept a journal during this challenging journey by sail, carriage, and freight canoe to the northern edge of the Prairies, where she would live for a short time at the HBC’s Fort Garry trading post in the Red River settlement (the land between the Red River and Assiniboine River), now around modern-day Winnipeg. Simpson wrote that during the voyage across the Atlantic, she was grateful to have had the company of Catherine Turner (1805-1841), the Scottish bride of HBC chief factor John George McTavish (c. 1778-1847). Turner was able to comfort Simpson in what she described as a time of “bitter sorrow” due to her sudden departure from her “dearest Mother and Sisters,” “beloved Father,” and the comforts of her home in London.16 Upon arriving in Montreal, Simpson would have little time to rest before continuing the journey, commencing a lengthy canoe trip from Lachine in Montreal to York Factory (the HBC headquarters in Rupert’s Land) in the early summer months of May and June under the guidance of several HBC members and dependent on the knowledge of the Canadian voyageurs and Indigenous guides. Importantly, Turner and Simpson were the first British women to travel across Canada on this canoe route, rendering Simpson’s diary a crucial written resource to contextualize the social history of the Canadian West.

Similar to other women of her class and nationality, Simpson was particularly focused on class, aesthetics, appearances, and race, a perspective which emerges in her written reflections from her journey in Canada.17 The first entry from her diary tells of the conditions and the supplies that would support the lengthy expedition from Lachine to Red River. On the first day of the journey, May 2nd, 1830, the Simpsons and MacTavishes left Lachine at 4 AM in two Canoes manned by 15 hands each. Simpson described the 30 voyageurs as “strong, active, fine-looking Canadians,” a term then used to refer to French Canadians. The passengers also included two unnamed maidservants, two HBC officers called James Keith and Samuel Gale, who she explains “kindly volunteered to favour us with their company for a day or two,” and an unknown number of Indigenous guides, only one recorded by name as “Bernard.”18

Travelling by River: The Canoe Journey Begins

In her diary, Simpson described their canoe as “a most beautiful craft, airy and elegant beyond description, was 35 feet in length,” continuing to describe the extensive cargo on the canoes. The canoes for the journey held significant weight, including:

2 Waterproof Trunks containing our clothes; 1 Basket for holding Cold Meat, Knives & Forks, Towels &c. 1 Egg Basket, a travelling Case containing 6 Wine Bottles, Cups & Saucers, Tea Pot, Sugar Basin, Spoons, Cruets, Glasses & Tumblers, Fishing Apparatus, Tea, Sugar Salt &c. &c.-also a bag of Biscuits, a bale of Hams, a Keg of Butter…

Simpson then describes the provisions for the crew, allowing a glimpse into how the voyageurs and guides nourished themselves on harsh journeys. The crew subsisted primarily on pork and biscuits, and she explains that due to their diet, “the young recruits are called ‘Pork Eaters’ to distinguish them from the old Winterers, who feed chiefly on ‘Pemican,’ a mixture of Buffalo Meat, Tallow, and a due proportion of hairs.”20 Pemmican, derived from the Cree word pimihkaan/ᐱᒥᐦᑳᓐ meaning “manufactured grease” or “mixture of dry powdered meat with fat,” was said to be “not the most delicate, but a very substantial food” but was filled with calories and Vitamin C, and was very portable, thus becoming attractive for long voyages.21 In addition to the food, the crew also had a keg of liquor called the Dutchman, “from which the people are drammed three or four times a day, according to the state of the Weather.”

Simpson recounts the jovial start to the journey where the voyageurs were singing, and “the Canoe almost flying thro’ the water-the motion is perfectly easy, & in fine weather, it is the most delightful mode of travelling that can be imagined.”22 At 9 AM on the first day, the two canoe crews “put ashore for Breakfast, above the Rapids of St. Ann,” where she wrote that Lady McTavish and herself “were carried in the arms,” and Mr. Simpson and Mr. McTavish “on the backs of our sturdy Canadians,” conjuring “a hearty laugh.”23 The crew then assembled firewood for a kettle and had a breakfast spread of “Cold Meat, Fowls, Ham, Eggs, Bread & Butter.”24 Simpson wrote fondly of the guide Bernard, who “kindled the fire with his Flint and Steel and a small piece of Bark and Touchwood” with which his “Fire Bag,” (sometimes known as an “Octopus Bag” by Europeans, depending on the shape of the bag) as she called it, was furnished.25

Simpson’s diary immerses readers in the material culture and provisions supporting long canoe journeys across Canada in the early nineteenth century. Her entries also demonstrate her reliance on the sense of sight when encountering new scenery, people, and communities. In addition to describing the conditions of the journey, she often made note of the sublime grandeur of the Canadian wilderness.26 For example, her entry from May 26th includes language of the grandeur and stupendous nature of the Canadian wilderness, describing the Paresseux Rapids as “one of the finest Falls in the Country is upwards of 100 feet in height dashing over stupendous rocks; boiling, foaming, and roaring with the noise of Thunder-the Spray flying in all directions appears studded with precious stones and surrounded by thousands of Rainbows.”27 This description bridges beauty and terror as well as Simpson’s passion, elucidated by the forceful power of the rushing water and the staggering beauty of the rocks towering into the sky.

References

1 ‘Geddes Mackenzie Simpson’, Legacies of British Slavery database, http://wwwdepts-live.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146631028 [accessed 6th August 2023].

2 Letitia Mactavish Hargrave, The Letters of Letitia Hargrave, edited by Margaret Arnett MacLeod. The Publications of the Champlain Society, 28, (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1947), 25-26.

3 Mactavish Hargrave, 25-26.

4 Mactavish Hargrave, 25-26.

5 The Regency era lasted from the mid 1790s until 1837 when Queen Victoria took the throne.

6 Ann B. Shteir, Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science : Flora’s Daughters and Botany in England, 1760-1860, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), 1996, 67. Example: Harriet Beaufort’s book Dialogues on Botany (1819).

7 Shteir, 30-1.

8 Shteir, 30.

9 Shteir, 93.

10 Last Will and Testament of Geddes Mackenzie Simpson, 27 Dec 1848.

11 In 1821 George Simpson was appointed Governor of the Northern Department of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Rupert’s Land was what the British called the large tract of land expanding from Hudson’s Bay, north to the Arctic, west to the Rocky Mountains, named and chartered by the British Crown in 1670 after Prince Rupert.

12 Sylvia Van Kirk, “The Role of Native Women in the Creation of Fur Trade Society in Western Canada, 1670–1830,” In Susan Armitage; Elizabeth Jameson (eds.). The Women’s West, (University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 55.

13 Neilsen Glenn, 117.

14 Lorri Neilsen Glenn, Following the River: Traces of Red River Women, (Hamilton, ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2017, 117).

15 Women in the Shadows, National Film Board of Canada, 2017, https://www-nfb-ca.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/film/women_in_the_shadows/, 29:00. Conversation with Sylvia Van Kirk.

16 Hudson’s Bay Company Archive, D.6/4, folio 2.; Sylvia Van Kirk, “SIMPSON, FRANCES RAMSAY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/simpson_frances_ramsay_8E.html.

17 Sylvia Van Kirk, Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-trade Society, 1670-1870, (University of Oklahoma Press, 1980), 174, 179.

18 Frances Simpson, Diary of Frances Simpson, May-August 1830, 2 May, 1830, UNB Women Writers Project, last modified March 1999, https://web.lib.unb.ca/Texts/WmWriters/texts/simpson1.html.

19 Credit: Library and Archives Canada / Acc. No. 1989-401-1 / e011153912.

20 Simpson, 2 May 1830.

21 Simpson, 2 May 1830.; East Cree Dictionary online, https://dictionary.eastcree.org/Words.

22 Simpson, 2 May 1830.

23 Simpson, 2 May 1830.

24 Simpson, 2 May 1830.

25 “The ubiquitous “fire bag” developed into several different forms during the fur-trade era. The “octopus” pouch with 8 pendant tabs, was popular with Métis in the Red River area in the early 1800s. The style spread north and west as far as the Pacific Coast, often acquiring, through beaded decoration, a distinctive regional character.” From: Harrison, Julia Diane, and Glenbow Museum, The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples, (McClelland & Stewart, 1987), https://books.google.ca/books?id=P1l1AAAAMAAJ, 108.

26 Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, 1757.: English concept of the sublime: “The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is astonishment…all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror….”

27 Simpson, May 26th 1830 entry.

Encounters: Judgement Based on Appearance

Written by Mallory Novicoff

View Essay

In the first entry of her diary, Frances Simpson recounts the first “friendly greeting” by Indigenous peoples to the travel party, including descriptions of several people representing different communities. On the afternoon of May 2nd, the party landed at the “beautiful Indian village of the ‘Lake of the Two Mountains,’” a culturally rich post near Oka and Kanesatake where the HBC established their presence after a contentious history.

The party was “saluted with a discharge of Artillery” upon arriving on the shore by the Chiefs of the “Iroquay, Algonquin, and Nepisang tribes.”29 The many Indigenous peoples greeting the party were, as Simpson explained:

decked out in all their finery of Ribbons, Beads, & Silver works, placed themselves in rows, on either side of the path leading to the house, and smiled, and appeared much pleased, when spoken to. The daughter of one of the principal Chiefs…came forward, and saying a few words in her native language, presented me with a Bouquet of Cherry Blossom very prettily arranged, as a mark of friendly greeting.30

Here, Simpson speaks relatively positively about the people greeting her. Simpson often included observations of the comportment of the people she encountered, followed by a physical description of their appearance and dress.

For example, when she encountered individuals around Lake Superior on May 17th, Simpson wrote that some of them appeared “Copper coloured, others of a dirty yellow, and some few of the Women & Children are nearly as fair as Europeans…”.31 On May 25th, Simpson favourably described the very “gaily dressed” Ojibwe Chief in Thunder Bay, who Anglophones colloquially knew as “the Spaniard” since he was said to have Spanish ancestry on his father’s side and was friendly with European traders. 32

Simpson wrote semi-complimentary about Indigenous men such as the party’s guide Bernard and the Ojibwe Chief called “the Spaniard.”33 These moments of praise were especially apparent when men dressed like Europeans with “fair complexions,” reminiscent of rising racialization.34 However, interactions at Red River between Indigenous women, Simpson, and her British friends like Letitia Hargrave were tense. Hargrave noted an instance where Simpson was dismissive of HBC officer James MacTavish’s former country wife, Nancy Turner, calling her a “complete savage with a coarse blue sort of Woolen gown, without shape & a blanket fastened round her neck…”.’35 This language by British women was perhaps a manifestation of insecurity towards women who used to hold significant societal influence and relations with their current husbands in the past.

Upon the arrival of British women into the interior of Canada, the customs of the fur trade were disrupted, where the once common marriage and ties between Indigenous women, British and French traders, and male members of the HBC elite became scarce. Following in Governor George Simpson’s footsteps, other HBC officers and British men in the region began choosing to have British wives, excluding their Métis families from the newly forming “high society.”36 George Simpson also stated that he wanted the British women to have “as little discourse with the Native women as possible,” requesting that teachers for HBC officer’s children to be “respectable English women” rather than local women.37 He further advised McTavish to keep himself and his British wife distant from Indigenous women just as Simpson had isolated his wife, exclaiming: “The greater distance at which they are kept, the better.”38 Frances Simpson’s diary illuminates the underlying yet harsh dynamics of social change and how the arrival of British women in the Canadian West underscored increasing class and racial distinctions. 39

Arrival at Norway House and Red River

In the final legs of the long journey and the last entries of her diary, Simpson focuses less on the appearance of others and more on how she was being treated and her experiences in an unfamiliar place. On June 14th, Simpson wrote that she arrived in a “pleasant situation” at Norway House (a meeting place of the Council of Rupert’s Land and a distribution centre for trade in Red River) on an elevated bank that was “dry and affording a fine shelter for the Craft and excellent Encampments for the people.”40 The Simpsons stayed at Norway House until June 22nd, when they would continue their journey to York Factory and back downriver to Fort Garry and the Red River settlement between the Assiniboine and Red Rivers at the end of August.

Credit: Library and Archives of Canada, Acc. No. 1988-250-22

On June 26th, Simpson reflected on her long canoe journey and arrival at York Factory. In this entry, she remarks on her bravery and the length and challenges of the journey:

Fond as I am of travelling, I felt pleased at the idea of remaining quiet for two months: having traversed in various ways (since the 8th of March) a distance of 8000 Miles, which for a Novice, is no small undertaking. I must here observe, that a Canoe voyage is not one which an English Lady would take for pleasure; and though I have gone through it very well, there are many little inconveniences to be met with, not altogether pleasing… 42

Simpson explained how many difficulties could be overcome by some measure, with “persons accustomed to travelling thro’ the Country in this manner” having more knowledge of how to overcome hardship. She claims that because George Simpson travelled often and had significant voyage experience, she was at the “greatest advantage” since he provided her with many things to aid in the comfort of the journey, including “Indian Rubber Shoes, Umbrellas, a thin Oil Cloth as a covering from the rain &c. &c.” She was also met with “the greatest kindness from all the Gentlemen” at Norway House and York Factory. Though she critiqued their manners, Simpson still felt that the men she encountered were “warmhearted, kindly dispositioned people; who offer to a stranger, the most cordial, and unaffected welcome, and endeavour to make every thing pleasing & agreeable.”43

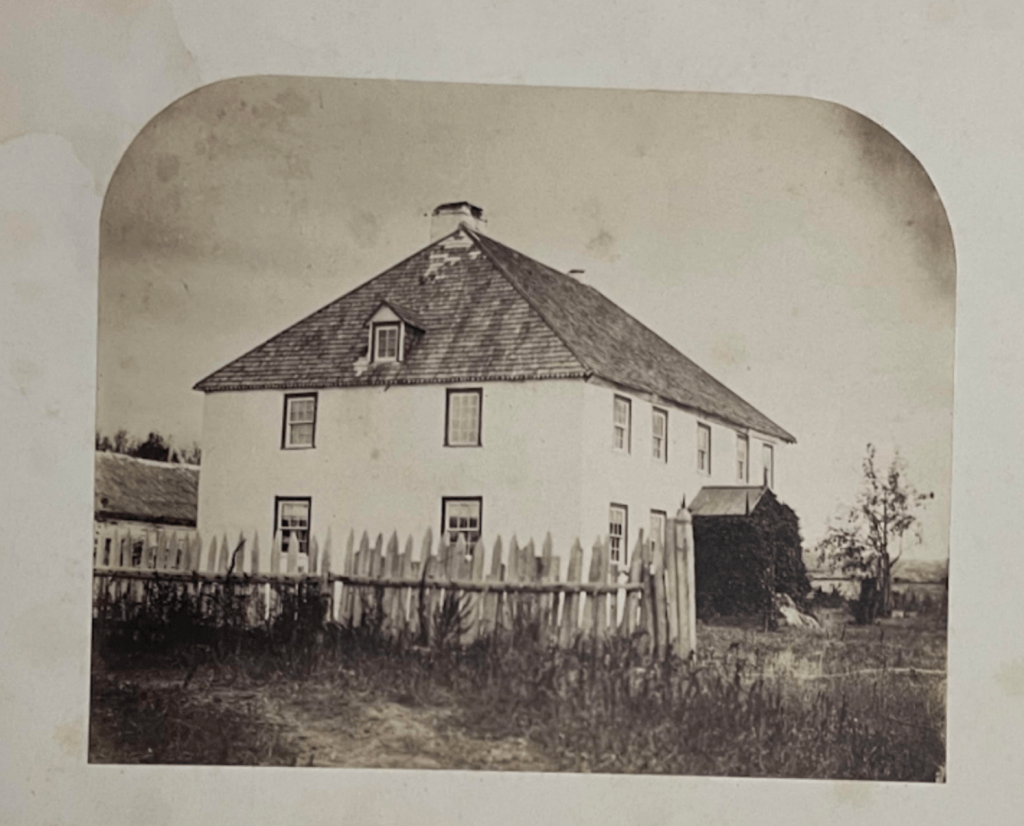

As the journey began to wind down around Lake Winnipeg, approaching the Red River settlement, Simpson began enjoying more of the comforts she was accustomed to in London. At the Red River settlement, she would be welcomed with the construction of a beautiful home, which was said to have been a feat of architecture for the time.44 However, despite having the comforts of the new house and financial support from her husband’s position in the HBC, she was still struck with loneliness, seclusion, and homesickness.

References

28 Unknown, A View of the Lake of Two Mountains with the Village on its North Shore, 1830. Library and Archives Canada: http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=2918492&lang=eng . Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1994-208-1.

29 Simpson, 2 May 1830.

30 Simpson, 2 May 1830.

31 Simpson, 17 May 1830.; Van Kirk, Many Tender Ties, 179.

32 Simpson, 25 May 1830.

33 Simpson, 25 May 1830.

34 Simpson, 17 May 1830.; Simpson, 25 May 1830.; Van Kirk, Many Tender Ties, 179.

35 Letitia Mactavish Hargrave, and Margaret Arnett Macleod, The Letters of Letitia Hargrave : [Ed.with Introd., and Notes by M.a. Macleod]. Facsim.ed. (New York: Greenwood Press, 1969), 34-6.

36 Van Kirk, Many Tender Ties, 177.; Galbraith, The Little Emporer, 112.

37 Neilson Glenn, 121.

38 Galbraith, The Little Emporer, 112.

39 Van Kirk, Many Tender Ties, 15.

40 Simpson, 14 June 1830.; http://parkscanadahistory.com/series/chs/4/chs4-1h.htm

41 https://thediscoverblog.com/2016/05/02/journey-to-red-river-1821-peter-rindisbacher/. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1988-250-22

42 Simpson, 26 June 1831

43 Simpson, 26 June 1831.

44 Women in the Shadows, National Film Board of Canada, 2017 https://www-nfb-ca.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/film/women_in_the_shadows/, 28:00. Conversation with Sylvia Van Kirk.

Red River Colony (1811-1870)

This colonization project began in 1811 on 300,000 square kilometres of land in British North America, granted to Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, by the Hudson’s Bay Company in the Selkirk Concession.

McCord Visit Review: Portraits and Visuals of 19th Century Red River

Written by Mallory Novicoff

View Essay

In February of 2023, I visited the McCord Museum archives and collections to explore some of the first photographs of Western Canada from the Red River settlement (in current-day Manitoba). The McCord Museum collections contain archives, belongings, items, and photographs from episodes of Canadian social history. The goal of the visit was to understand better the landscape of Red River, the lifestyle of the Métis and Anishinaabeg who lived there, and the navigation methods used by Canadian, European, and Indigenous voyageurs passing through the region in the mid to late nineteenth century. Thus, I chose photographs from the McCord online catalogue depicting canoes, the river itself, different architectural methods for housing, Hudson’s Bay Company offices and hubs like Norway House, prominent churches, and portraits of Ojibwe, Cree, and Métis individuals from the region.

These photographs came from a collection from the Canadian government-sanctioned Assiniboine and Saskatchewan expedition led by Henry Youle Hind (b. 1 June 1823 Nottingham, UK; d. 8 August 1908 Windsor, ON) in 1858. Humphrey Lloyd Hime (b. 17 Sept 1833; d. 31 Oct 1903) was a photographer and surveyor on this expedition. Due to the quality and date of his photos, he became a Canadian photography pioneer.1 The primary objective of the 1858 expedition was to “thoroughly examine the prairies between Lake Superior and the Red River to find the best route for official communication through British territory and find tracks of cultivable land beyond,” with Hime’s photographs reflecting this vision.2

The expedition crew left Toronto on April 29, 1858, trekking west to Detroit, canoeing through the Great Lakes over Grand Portage, similar to the Simpson’s voyage two decades earlier, and arriving at the Red River settlement on the first of June. Here, Hime took the first photographs of Western Canada.3 The number of photos Hime took is unknown, and only a few survived until the 20th century, but those that remain provide invaluable glimpses into what life was like at Red River in the mid-nineteenth century.

The expedition report describes the Iroquois guide Chariot Skan-a-sah as an “intrepid and skillful pilot in the dangerous navigation of the Winnipeg River.”4 Upon arriving at Red River, the Iroquois voyageurs from the East were exchanged for local Cree-Métis individuals with more knowledge of the Prairie terrain. Additionally, at Red River, George Simpson, still governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the 1850s, assisted Hind in procuring canoes and supplies from the company’s forts on the voyage route, aiding the expedition’s progress.

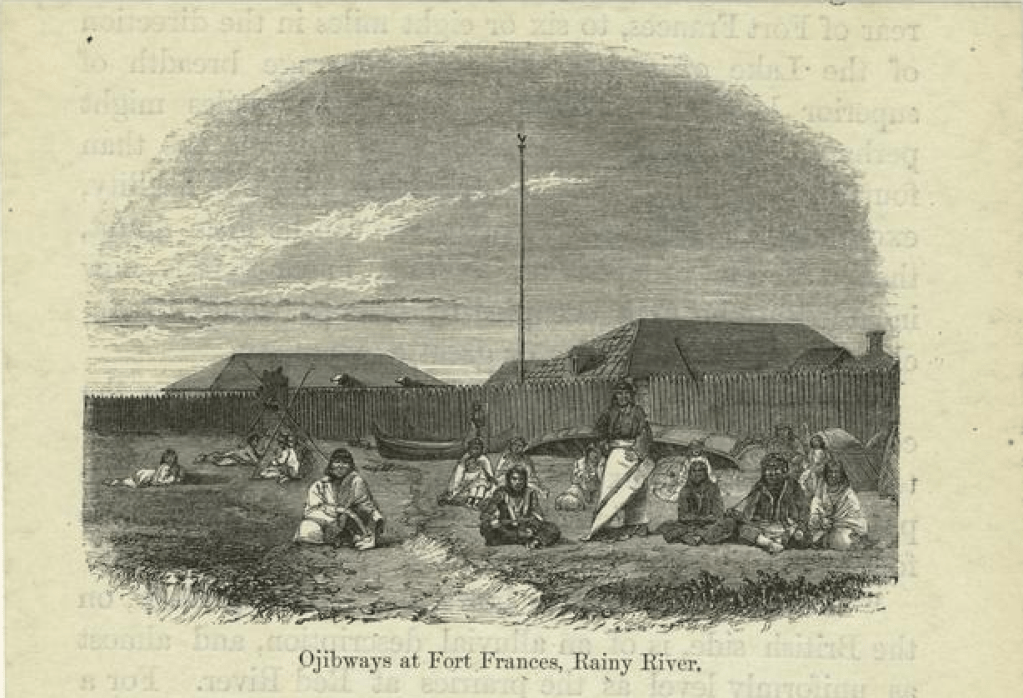

In May 1858, the Hind expedition passed through Fort Frances in western Ontario, named after George Simpson’s wife, Frances Simpson. At Fort Frances, Hime photographed Ojibwe birch-bark wigwams with sturgeon drying on poles.5 Unfortunately for me, this photo is kept at the Toronto Public Library Canadian History and Manuscript Section and is the only known original photo print of Hime’s photos of Ojibwe peoples and of Fort Frances, which are mounted and bound in a scrapbook album.6

After passing through Ontario, Hind’s crew arrived at Red River five days before George Simpson. They camped near the mouth of the river on June 1 and settled in the afternoon of the following day.

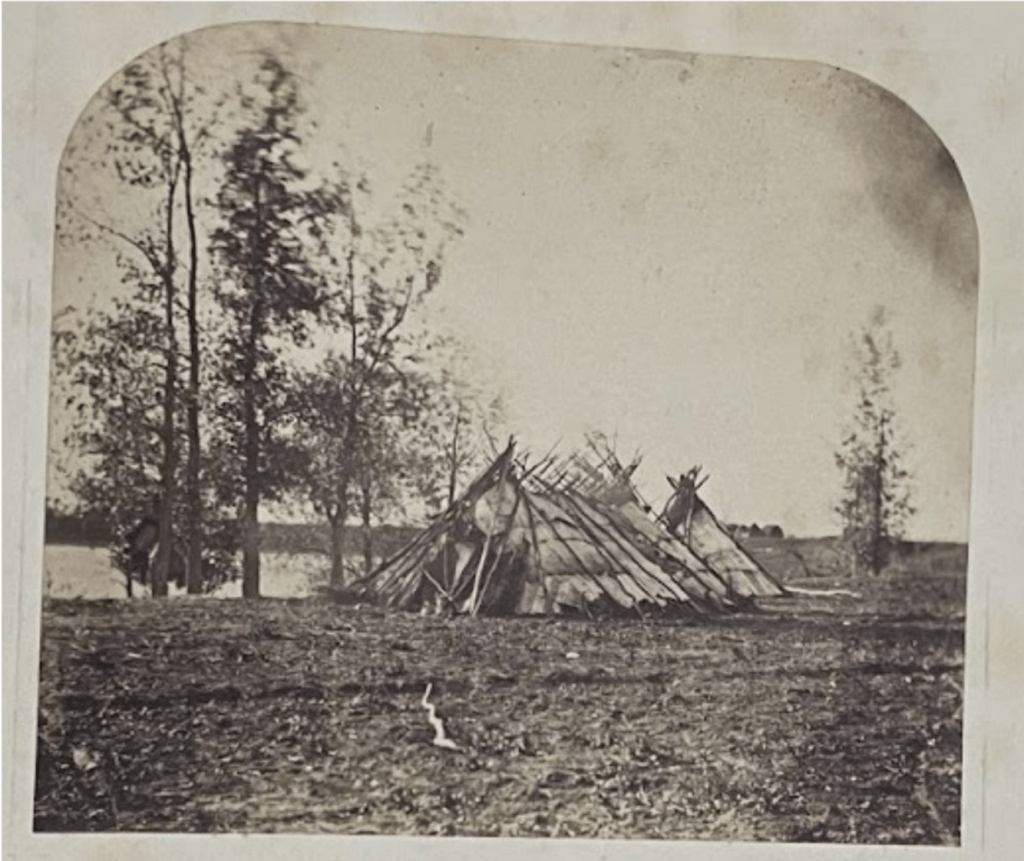

From September through November 1858, Hime stationed himself in Red River, taking about thirty-five known photos around the settlement (the bulk of his surviving collection). These photographs are a tribute to his photographic and artistic skill and an important visual record of the settlement as it existed in 1858.8 During my visit to the collections, I saw photographs of the broad expanse of the prairies and wide shots of the various structures like homes and churches along the Red River, including St Boniface Cathedral and St Andrews at the Grand Rapids.

Credit: McCord Stewart Museum

Credit: McCord Stewart Museum

Credit: McCord Stewart Museum

Hime’s photos from the 1858 Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition exist as original prints, copy prints, and contemporary reproductions in the Illustrated London News and in Hind’s Narrative of Canadian Red River Exploring Expedition of 1857 and of the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition of 1858.9 The prints at the McCord Collections are copies of the originals since none of the original glass plate negatives survived.

Though it is unknown exactly how many photos Hime took on the three-month journey, he packed 200 glass plates to bring to Red River.10 Processing wet plate collodion photography was difficult in the Prairie terrain due to unreliable local water sources. The quality of the photographs we see today is remarkable, considering the natural obstacles Hime faced on the journey.

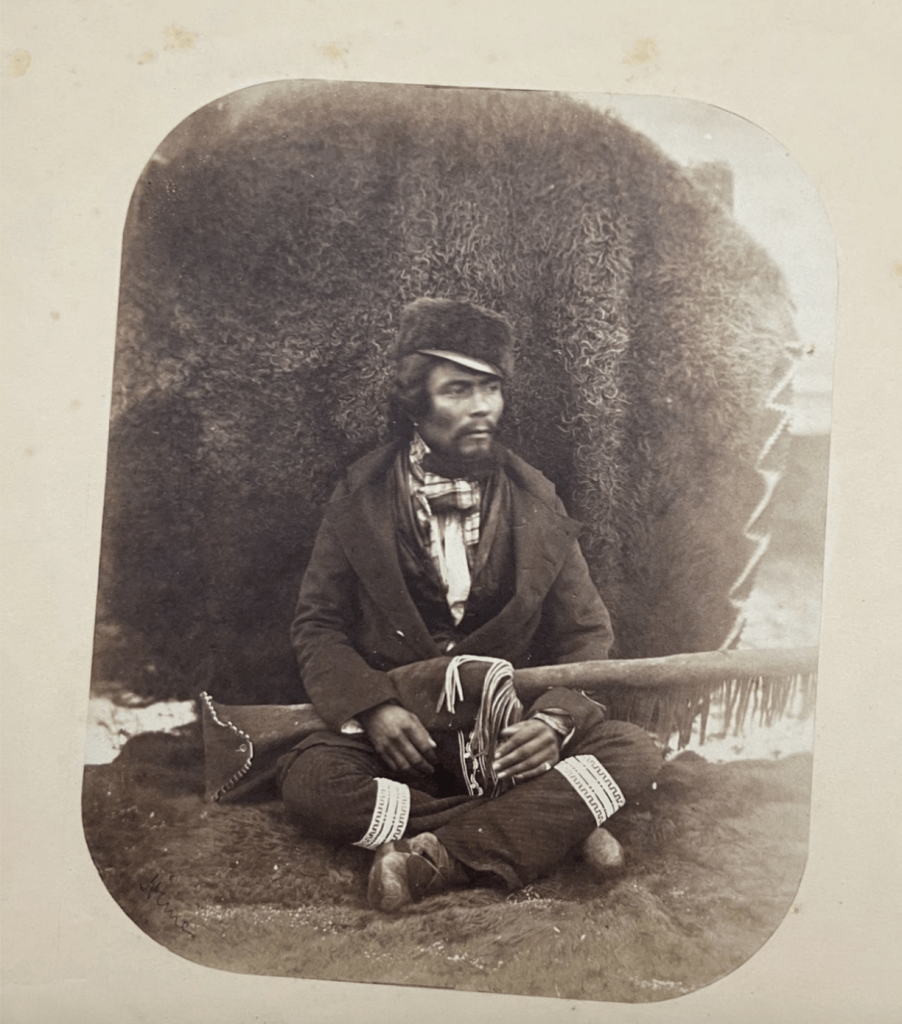

Most of the existing photos are from his time at the Red River settlement and around the river valley from September to November. Hime remained at the Red River settlement in September while Hind and other expedition members travelled back to Lake Winnipeg. During this time, Hime took photos of churches, scenes, buildings, and Indigenous peoples for an “interesting collection,” as Hind reported later on, changing his view on the quality of Hime’s work over time from praiseworthy to critical.11 A list of the photographs at the McCord Museum states that six are of “the River itself and the level country through which it flows,” and fifteen are of the architecture of the churches, houses, stores, HBC buildings, and Forts. There are also four views of tents, one close-up of a Blackfoot Robe, and five portraits of Red River inhabitants: John McKay, Wigwam, Letitia Bird, Jane L’Adamar (“Susan”), and an Ojibwe woman with a papoose (baby carrier).

After the expedition, Hime’s photographs were displayed at the Fine Arts Section of the Provincial Exhibition in Kingston, Ontario, from September 27 until September 30, 1859. Additionally, all of the voyage reports, tables, lithographs, maps, and a list of Hime’s photos were published in September 1859 as a Government Blue Book, attracting attention from the Canadian press.12 A portfolio of these prints was published in 1860 by the Canadian government alongside a list of the photographs that Hime took on the expedition.13

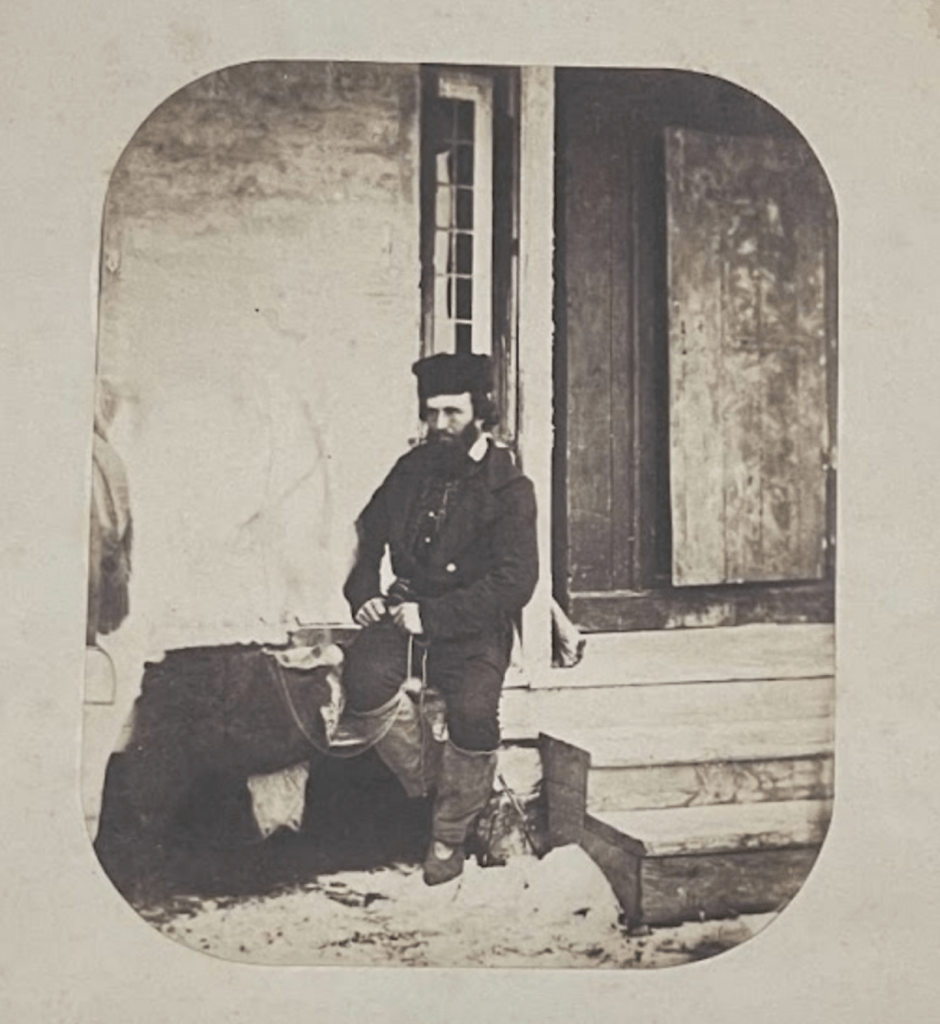

Hime’s five portraits lend themselves incredibly well to inquiring about fashion trends and individuals of the time. He included the names of the people he photographed and their community, some Métis, another Cree, and another Ojibwe; the portraits are not stiffly stylized but in loose, natural outdoor settings, which was likely an attempt to demonstrate the natural setting of the Red River settlement. Though Hime’s original captions provide a brief identification of the people, it would have been helpful had Hime or another member of the crew provided “additional historical information to explain the significance of the individuals in the photographs concerning the setting and society of Red River.”14

Credit: McCord Stewart Museum

Credit: McCord Stewart Museum

Susan (or Jane) and Letitia are wearing very similar dresses, likely the common calico dresses that Red River Métis women wore in the 1850s. In the mid-1800s, though the decorated moccasin remained the popular footwear, as seen on Letitia and Jane’s feet, the rest of Métis fashion became more “Europeanized.” As more Europeans (particularly British women and male officers) moved west into the Red River region throughout the 1850s and 1860s, photographs like those of Letitia and Jane show more “up-to-date” European clothing, such as the printed calico dresses with wide sleeves.17 Though many women covered their hair with shawls, Letitia and Jane did not wear one in the portrait. Whether this is a stylistic choice or the women did not wear a shawl in their daily lives, we do not know.18

Image Credit: McCord Stewart Museum

Credit: McCord Stewart Museum

Though there are some portraits of Indigenous peoples, an issue of The Illustrated London News focusing on the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan expedition revealed that the expedition members claimed that many Indigenous peoples did not want their photos taken since they feared that the photographs would be used maliciously, perhaps to have them killed or removed from their lands.20 As such, the surviving portraits are incredibly rare and unique due to their age, the names accompanying them, and the very few Red River people who consented to pose for a portrait.

Hime’s photographs of the Red River settlement are well-preserved and valuable documents for understanding the 19th-century Canadian Prairies, the journeys of voyageurs, and the roles of Anishinaabeg and Métis guides. They also provide glimpses of the diverse and knowledgeable residents of the settlement. Whether or not the expedition leader, Hind, was content with Hime’s photography and overall performance is a matter of debate.21 However, these photographs are the earliest glimpses of life at Red River, a crucial hub for local Métis, Ojibwe, and Cree communities, as well as Hudson’s Bay Company officers.

References

1 Huyda, Richard J.. “Humphrey Lloyd Hime.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published February 05, 2008; Last Edited March 04, 2015.

2 S.J. Dawson, George Gladman, Henry Youle Hind, Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition, Canadian Red River Exploring Expedition, Report on the exploration of the country between Lake Superior and the Red River settlement, (Toronto?: publisher not identified, 1858), Canadiana, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.44219.

3 Brock V. Silversides, Looking West: Photographing the Canadian Prairies, 1858–1957, (Fifth House Publishers, 1999), 4.

4 The Illustrated London News, 1858

5 Huyda, 28, 29.

6 Huyda, 28, 29. Due to a cyber crisis, the TPL is slowly restoring their normal online services. This photo is not digitally available at the moment but a woodcut of this photo is in Hind’s review of the expedition.

7 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Ojibways at Fort Frances, Rainy River” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-1a84-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

8 Sylvia Van Kirk, “Camera in the Interior, 1858: The Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition by Richard J. Huyda (Review,.” The Canadian Historical Review 58, no. 3 (1977): 318–19, 318.

9 Huyda, 32, 33.

10 Huyda, 19.

11 Huyda, 22, 23.

12 Huyda, 23, 26, 27.

13 Huyda, 23, 26, 27.

14 Van Kirk, 319.

15 McKay, Letitia Bird (B. 1810) – Uploaded by Lawrence J. Barkwell.; Huyda, 37.; Sylvia Van Kirk. Many Tender Ties. Women in Fur Trade Society, 1670-1870.

16 Huyda, 38,; McCord Catalog.

17 Pamela Blackstock, “Nineteenth Century Fur Trade Costume”, Ethnologies 10, no 1-2 (1988) : 183–208, https://doi.org/10.7202/1081457ar, 202.

18 Blackstock, 202.

19 Patrick Young, “Traditional Métis Clothing,” Métis Museum, May 30, 2003, https://www.metismuseum.ca/resource.php/00745.; The rifle case resembles a similar one from around the same period at the Manitoba Museum included in this article: Amelia Fay, “Gun Case,” Gun Case – Canada’s History, May 7, 2018, https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/fur-trade/gun-case.

Image References

*All images were taken by the author at the McCord Stewart Museum collections visit in Feb. 2023

Humphrey L. Hime, St. Andrew’s Church Rapids Church, 1858, m24588.10, McCord Stewart Museum.

Humphrey L. Hime, Tents on the Prairies West of the Settlement, 1858, m24588.18, McCord Stewart Museum.

Humphrey L. Hime, Ojibway tents on the banks of the Red River near the Middle Settlement, 1858 m24588.17, McCord Stewart Museum.

Humphrey L. Hime, Quarters of the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition, Middle Settlement, 1858, m24588.15, McCord Stewart Museum.

Humphrey L. Hime, Residence of Chief Factor (Mr. Bird) Middle Settlement, 1858, m24588.12, McCord Stewart Museum.

Humphrey L. Hime, Residence of Chief Factor (Mr. Bird) Middle Settlement, 1858, m24588.12, McCord Stewart Museum.

Humphrey L. Hime, Letitia Bird, a Cree-Métis…, 1858, m24588.28, McCord Stewart Museum.

Humphrey L. Hime, Susan, a Swampy Cree Métis…, 1858, m24588.28, McCord Stewart Museum.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Ojibways at Fort Frances, Rainy River” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-1a84-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Bibliography

Blackstock, Pamela “Nineteenth Century Fur Trade Costume”. Ethnologies 10, no 1-2 (1988) : 183–208. https://doi.org/10.7202/1081457ar.

Dawson, S.J., George Gladman, Henry Youle Hind, Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition, and Canadian Red River Exploring Expedition. Report on the exploration of the country between Lake Superior and the Red River settlement. Toronto?: publisher not identified, 1858. Canadiana, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.44219.

Fay, Amelia. “Gun Case.” Gun Case – Canada’s History, May 7, 2018. https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/fur-trade/gun-case.

Hime, H. L, and Richard J Huyda. Camera in the Interior, 1858 : H.l. Hime, Photographer : The Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition. Toronto: Coach House Press, 1975.

Huyda, Richard J.. “Humphrey Lloyd Hime.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published February 05, 2008; Last Edited March 04, 2015.

Silversides, Brock V.. Looking West: Photographing the Canadian Prairies, 1858–1957. Fifth House Publishers, 1999.

“The Assiniboine And Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition.” The Illustrated London News Vol. XXXIII, No. 941 (Oct. 1858): 366-367.

Van Kirk, Sylvia. “Camera in the Interior, 1858: The Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition by Richard J. Huyda (Review).” The Canadian Historical Review 58, no. 3 (1977): 318–19.

Van Kirk, Sylvia. Many Tender Ties : Women in Fur-Trade Society, 1670-1870. Winnipeg, Man.: Watson & Dwyer, 1999.

Young, Patrick. “Traditional Métis Clothing.” Métis Museum, May 30, 2003. https://www.metismuseum.ca/resource.php/00745.