CHSTM Working Group

From September 2024 to July 2026, the Hidden Hands in Colonial Natural History working group on the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine (CHSTM) is hosting a series of talks and discussions on hidden hands in natural history collections worldwide. Please join us by creating an account on the CHSTM site and joining our working group.

Rare Books Exhibition

December 17th – 22nd, 2024

Bombay Natural History Society and McGill University Libraries

Premchand Roychand Gallery, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai

Overview

In collaboration with McGill University Libraries, the Bombay Natural History Society will display rare books at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai from December 17th to 22nd, 2024. The exhibit will include first edition copies of works by prominent naturalists from the 19th century such as Patrick Russel, John Gould, and Nathaniel Wallich. It will also include natural history illustrations, including illustrations from field guides by John Gould, and James Forbes.

You can read an article about the exhibition in the Deccan Herald, here.

Hidden Hands at Daphne

May 9th, 2024

Organized by Dr. Victoria Dickenson, Dr. Anna Winterbottom, and Mallory Novicoff

Centre d’art daphne, Montreal

Artists’ and Curators’ Roundtable

Photo Essay

Written by Dr. Anna Winterbottom

The workshop and roundtable were organised by the McGill-based “Hidden Hands in Colonial Natural Histories” project, in collaboration with daphne, a small Indigenous-run art gallery and took place in daphne’s space in Mile End. The Hidden Hands project is made up from four case studies and this workshop involved artists and curators working with three of these projects, focused on Canada, Haiti, and India. The aim of the day was to explore how practice-based methods could help us understand and reinterpret the historical materials that formed the starting point for the project. The day began with a dry smudge by Lori Beavis, Director of daphne, using homegrown tobacco and sage. The smudge is a form of cleansing often used to promote harmony. The smudge was done around an altar that was built by Montreal-based Haitian visual artist Clovis-Alexandre Desvarieux, using plants that were growing in the local area.

Read More

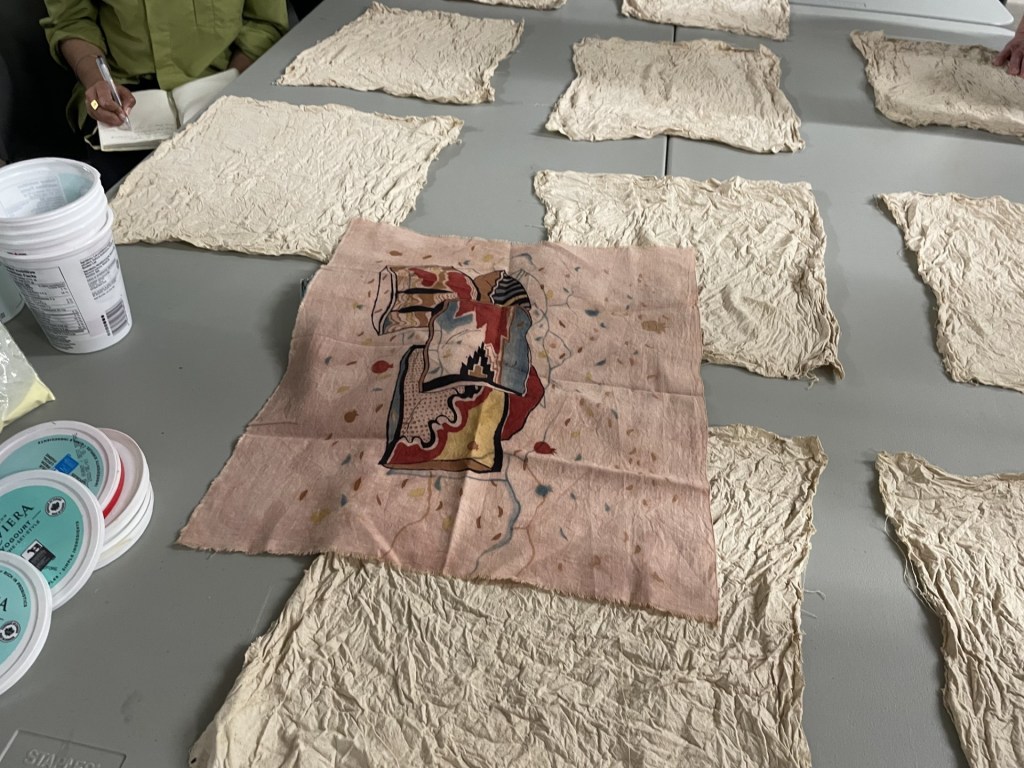

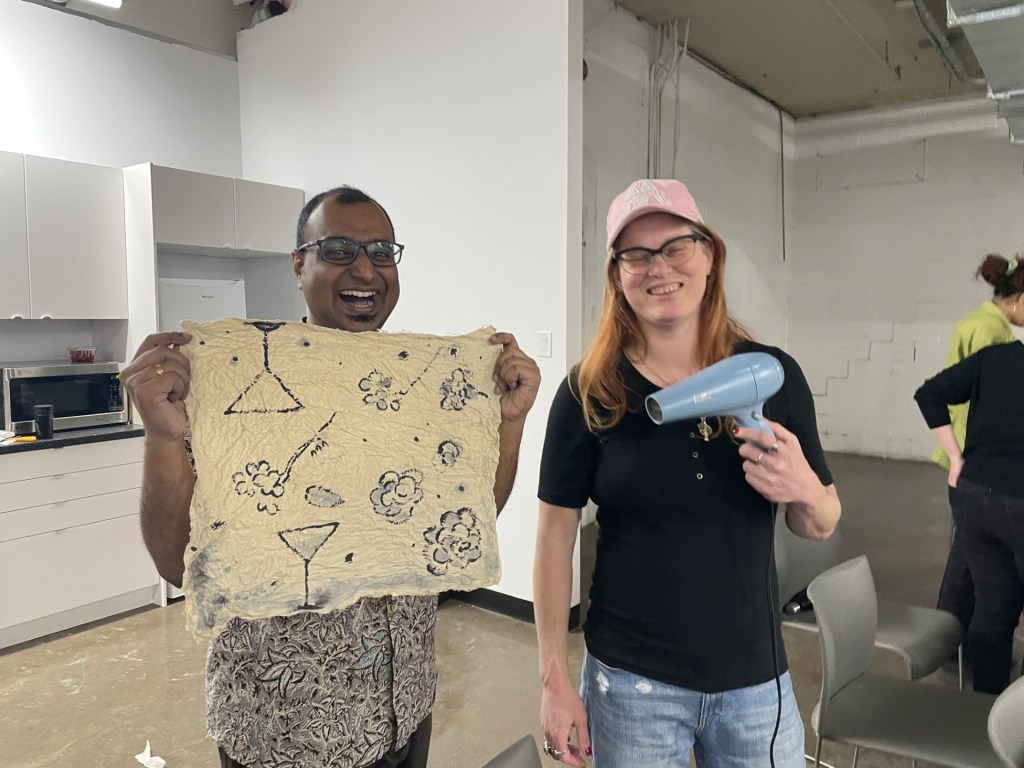

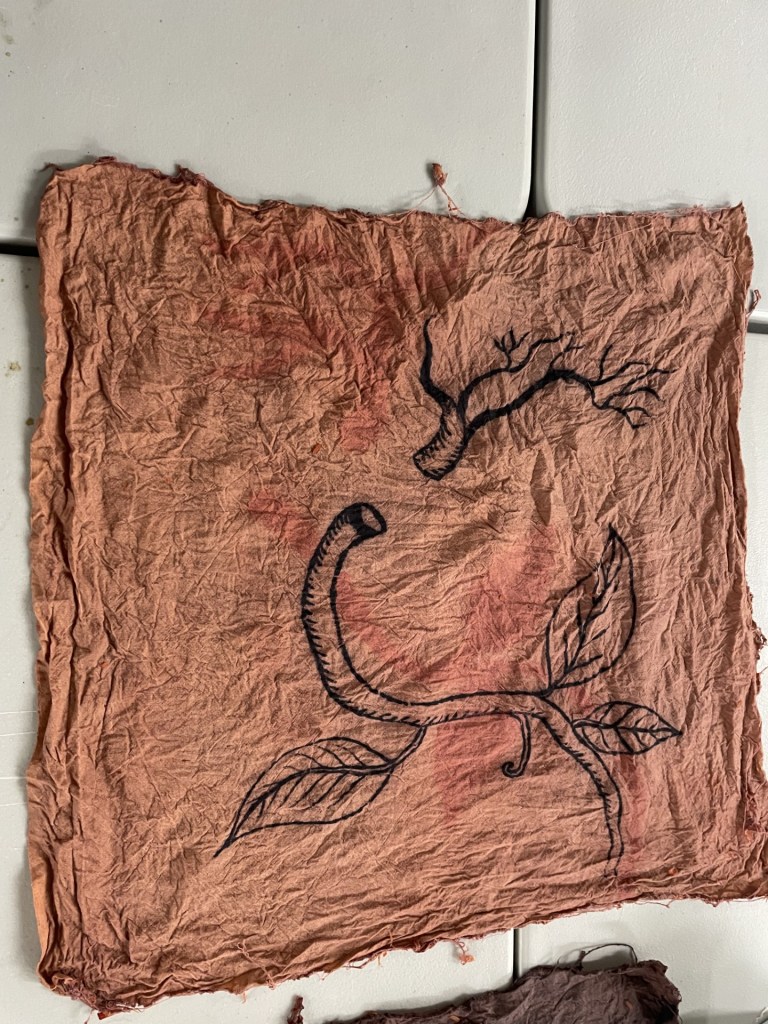

Rajarshi Sengupta, a practitioner and assistant professor at IIT Kanpur, focused on the history of textiles, then led a workshop on natural dyes. The fabric used was unbleached cotton and each person involved had a small square with which to work. The first step was to prepare the fabric using myrobalans (Terminalia chebula), which removes starch and helps the colours to stay once the dyeing is complete. Alum is used as a mordant, which helps to fix the dye on the fabric. Once the cotton had been treated, it was time to paint the design on the fabric using a solution made from iron and water (scrap iron can be recycled for this purpose). Rajarshi’s beautiful botanical drawing, inspired by his archival work on the Forbes archive, demonstrated for us the historical interactions between painting on textiles and painting for botanical work. Once the painting of the textiles was complete, they were soaked in a mixture of sappanwood (Biancaea sappan) and Areca catechu. This produces a range of reddish colours. We left them the textiles to dry (speeding the process up on a cool spring day with a hairdryer!) while moving on to the next part of the day. The textiles that were dyed first were a lighter colour, with those done later taking on a purplish colour as some of the iron solution soaked into the dye bath. Related to this was an interesting discussion that came up about the role of Durga, a mother goddess, as goddess of unintended consequences!

The second part of the day was a roundtable discussion led by Lori Beavis, who introduced each of the panelists, Clovis-Alexandre Desvarieux and Rajarshi Sengupta were joined by Gloria Bell, Assistant Professor in Art History at McGill; Juliet Mackie, multidisciplinary artist and jeweller and PhD Candidate at Concordia; Siobhan Mei, a translator and literary scholar and Lecturer in Information and Computer Science at Amherst. Victoria Dickenson, Professor of Practice at McGill and the PI for the Hidden Hands project, joined the panel to give a brief overview of the Hidden Hands network. Key themes that emerged from the discussion included: who is allowed to touch and interact with museum collections; the question of terminology; the interface between material belongings, colonial archives and digital entities; and the relevance of colonial archives and museum collections for today. Below is a brief summary of the conversation, which has been edited for length.

Several of the participants had visited collections at McGill and the McCord Museum and spoke of it being a moving and emotional experience. Juliet described the emotions around seeing the beadwork pieces in the museum context and how the interactions with them were limited by not being allowed to touch them or get too close to them because they may have been treated with chemicals that would be toxic to ingest. On a repeat visit, she described being able to bead alongside the historical materials and how spending time with the historical materials led her to pursue making flat-stitch pieces, inspired by the octopus bags that formed part of this collection.Clovis described visiting the Rare Books Department of the McGill libraries to look at the Rabié drawings as also being a very powerful and intimate experience. Firstly, in terms of discovering a new artist and the intent behind their work, but secondly because the drawings are revealing about the natural and colonial history of Haiti and the dynamics and contemporary legacies of that history. Rajarshi described how working with historical textiles is similarly eye-opening, but again, much is lost, particularly the knowledge of the people who created the textiles. He mentioned a visit by a wood-block maker and a dye specialist from southeastern India to the Royal Ontario Museum. While their instinctive response was to touch the textiles, this was not allowed in the museum context. Lori mentioned some cases in which Indigenous communities have partnered with museums, like the UBC Museum of Anthropology to establish their right to access and touch belongings. Gloria also questioned why conventions around who has the right to touch in the museum setting were not shifting faster, while also noting some current work by the Canadian Museums Association on repatriation and conservation, including using Indigenous conservation methods.

Lori suggested the idea of “beading with the ancestors” for Juliet’s practice and this began a discussion around language and terminology. Lori recalled an earlier project in which moving from talking about “objects” to discussing “ancestors” was helpful in shifting the mindset of the group. In response to a question from the audience about whether the term was anthropomorphic, Juliet responded that anything with a life-force might be considered an ancestor. Clovis added that the idea of ancestors reminds us that we are all made from the same fabric. A comment from Michelle Smith, Assistant Professor in the Department of Integrated Studies in Education at McGill and a member of the Hidden Hands project, highlighted that fact that colonial collectors often assumed that the cultures that they were documenting would be extinct, and how engaging with these collections as descendants of the makers of cultural belongings pushes back against these assumptions. Juliet noted the lack of information about origin communities on museum labels and in catalogues, compared with often lengthy biographical entries on the colonial collectors. Clovis pointed out that the history of natural history is very much the “knowledge of now”, in that many of the plants and animals drawn by de Rabié still exist in Haiti, although the knowledge of them is rarely taught in schools, in part a legacy of colonial curricula and textbooks.

Discussing the interface between the material belongings, colonial archives, and digital entities, Rajarshi noted the way that colonial archives filter nature, so that only those things consider “valuable” (usually in economic terms) remain. Seeing the collections in person reveals things that are not revealed in digitised archives, such as pencil marks, deletions and additions. Siobhan noted that as scholars we now also spend much time engaging with materials online. In the Hidden hands project, most of the collaborators engage with the materials in digitised form.While this is helpful in providing access, much information is lost – as is the connection with the material entity. Siobhan also noted the potential of digital archives for restructuring knowledge, citing the example of the Waterloo museum, which has a large collection of Haitian art and is thinking through ways to reorganise it using Creole categories of knowledge. Victoria noted the importance of embedding the findings of the Hidden Hands project in library and museum databases, to enrich and add layers to the collection.

Several participants spoke about the power of doing, as opposed to observing at a distance. Juliet spoke about how beadwork came naturally to her and provided a sense of connection with female ancestors. Clovis and Siobhan both spoke about how creating something together, like the dyed textiles we made in the morning gave a sense of connection to one another and was a more connected form of learning than learning something from TikTik or YouTube would have been. Rajarshi observed that doing something as opposed to just reading about it helps to understand the amount of work, practice, and skills that something like using plants to make dyes requires. The lived reality of practice removes the distance that comes with regarding belongings as “objects”. Clovis described his altars as a way of being with plants in the immediate surroundings and how “materiality brings us back to common humanity”. Siobhan brought up the notion of the everyday and the invisible labour which is often women’s work. Lori agreed that women’s work is often difficult to attribute to a single person, because women worked together. She raised an interesting example of the porcupine’s quills, which cannot be used in the summer because after the porcupine gives birth, its quills are filled with a milky substance. This shows how much of the specialist knowledge that went into producing material belongings is lost in the archives. Gloria described material belongings are histories in material form, observing how the hummingbirds in beaded leggings serve as a connection to hummingbirds in Anishinaabe legend.

Looking forward, the panelists discussed the potential of art and practise for moving beyond colonial mindsets. Regarding decolonisation efforts within universities, museums, and libraries, Juliet expressed concerns that efforts tended to be short-term and led by Indigenous people, often with little support from institutions. Clovis argued that these institutions will remain colonial, but that it is possible to create decolonial spaces within them. He suggested that reactions to historical materials do not need to be in the form of written descriptions, but could take otherforms like songs, dances, or drumming. Several panelists talked about how art reminds us to be human and to be respectful of the natural world. Clovis spoke about his altars as ways of being with plants in the immediate environment. The discussion ended with a lively question session and lots of food for further thought and discussion.

Hidden Hands in Colonial Natural History Collections: Reports from the Archives

June 19th, 2024

Chaired by Dr. Victoria Dickenson

Canadian Historical Association

Overview

Lectures:

- Anna Winterbottom – Trading, collecting, and depicting Indian Ocean animals: evidence from the James Forbes archive

- Matthew Barreto – Reading the collection: new perspectives on colonial ways of knowing

- Mallory Novicoff – Collecting plants in the Métis homeland: Frances Simpson in Red River

- Olivia Moy – The Devil’s Horseman: Mantis as carrier of knowledge

Painting Animals in 18th-Century Saint-Domingue

April 17th, 2024

Animal History Group – Event Page

Overview

Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) was the richest colony in the French Empire in the 18th century. Columbus visited the island of Hispaniola in 1492 and described great flocks of parrots darkening the skies. By the time the French engineer René Gabriel de Rabié (1717-85) arrived in 1742, the environment had been impacted by the intensive agriculture of sugarcane, coffee, indigo and cocoa plantations worked by enslaved peoples.

In the 1760s, de Rabié began to paint the plants and animals he encountered around his home in Cap Français and on his travels around the coast. By the time he left the island to return to France in 1784, he had amassed hundreds of watercolour drawings, as well as notes on habitats, habits and local names. He was assisted in this enterprise of natural history documentation by his daughter Jacquette Anne Marie Rabié de la Boissière and by the many enslaved people who worked as gardeners, cooks, household servants, fishers, paddlers and divers.

De Rabié was not the only European to document the novel (to him) flora and fauna he encountered in Saint Domingue. In addition to published records, there are numerous manuscript journals and drawings by engineers, members of the French military, doctors and plantation owners. These works reveal not only a European framework for the natural world, but also provide insight into the ways enslaved African and Indigenous peoples viewed this environment.

The four albums of de Rabié’s paintings are now preserved in the Blacker Wood Natural History Collection of McGill University Library in Montreal. Through close reading of original images, manuscript notes and published records, and through discussions with contemporary Haitian experts and residents, our research group is attempting to understand better how animals and people interacted on Saint Domingue in the 18th century, and how we can ensure a more inclusive documentation of historical records.

This research is part of the three-year research project Hidden Hands in Colonial Natural History Collections, funded through the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Sri Lankan Medical Manuscripts

September 22nd, 2023

Overview

The Osler Library contains 20 olas (palm leaf manuscripts) from Sri Lanka on medical subjects written in Sinhala, Sanskrit, and Pali. There is also a collection of around one hundred Sri Lankan olas in the Rare Books and Special Collections department of the McGill Library, many of which deal with medical or zoological topics. These manuscripts date from between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries and were collected in the 1920s and 1930s by Dr. Casey Wood. These manuscripts are not yet available digitally and most are not catalogued. While some are copies of well-known texts, others are rare or otherwise unknown. In this talk, Dr. Perera will discuss the contents of the olas at McGill, noting some interesting features of the manuscripts. He will place these manuscripts in the wider context of efforts in Sri Lanka to digitize and catalogue medical manuscripts, as a key part of the nation’s cultural heritage.

“I Paint Birds and I Don’t Care Where They Come From”

October 17th, 2023

Overview

The eighteenth and early nineteenth century was a period of discovery and accumulation of ornithological knowledge. During the period, preservation techniques of birds were not known nor were there any cameras to capture images of birds that were being discovered. Painting birds was one way to document them, and there were many artists who painted birds with the sole purpose of illustrating the amazing diversity of birds found in India. A close examination of the archival collections of Indian bird paintings from an ornithological perspective, indicates that these bird paintings were mere portraits. In other words, the artists who made them were primarily painters who did not study their subjects in their natural settings or focus on depicting their habitat affiliations or habits in the backgrounds. Invariably, the backgrounds were added as an afterthought to enhance the aesthetic value of the paintings. Most of the subjects painted were held in aviaries or open menageries, which were made possible by hidden hands whose efforts remain unrecognized. This talk will focus on this unexplored aspect of eighteenth and early nineteenth-century Indian bird paintings, with reference to the bird paintings at McGill, including those by Elizabeth Gwillim, James Forbes, Thomas Jerdon, and several unnamed Indian artists.