These essays are meant to bring information about collectors, collections, and hidden hands to light.

James Forbes (1749–1819)

British artist and writer

Digital Exhibition

Documenting the rare book exhibition held at the Premchand Roychand Gallery, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai, December 2024

Hidden Hands in Colonial Natural Histories is a collaborative research project based at McGill University. Our partner in India is the Bombay Natural History Society. The project seeks to uncover unacknowledged contributions to natural history collections made during the colonial period. One of four case studies focuses on the archive of James Forbes (1749–1819), author of Oriental Memoirs (1813).

Read More

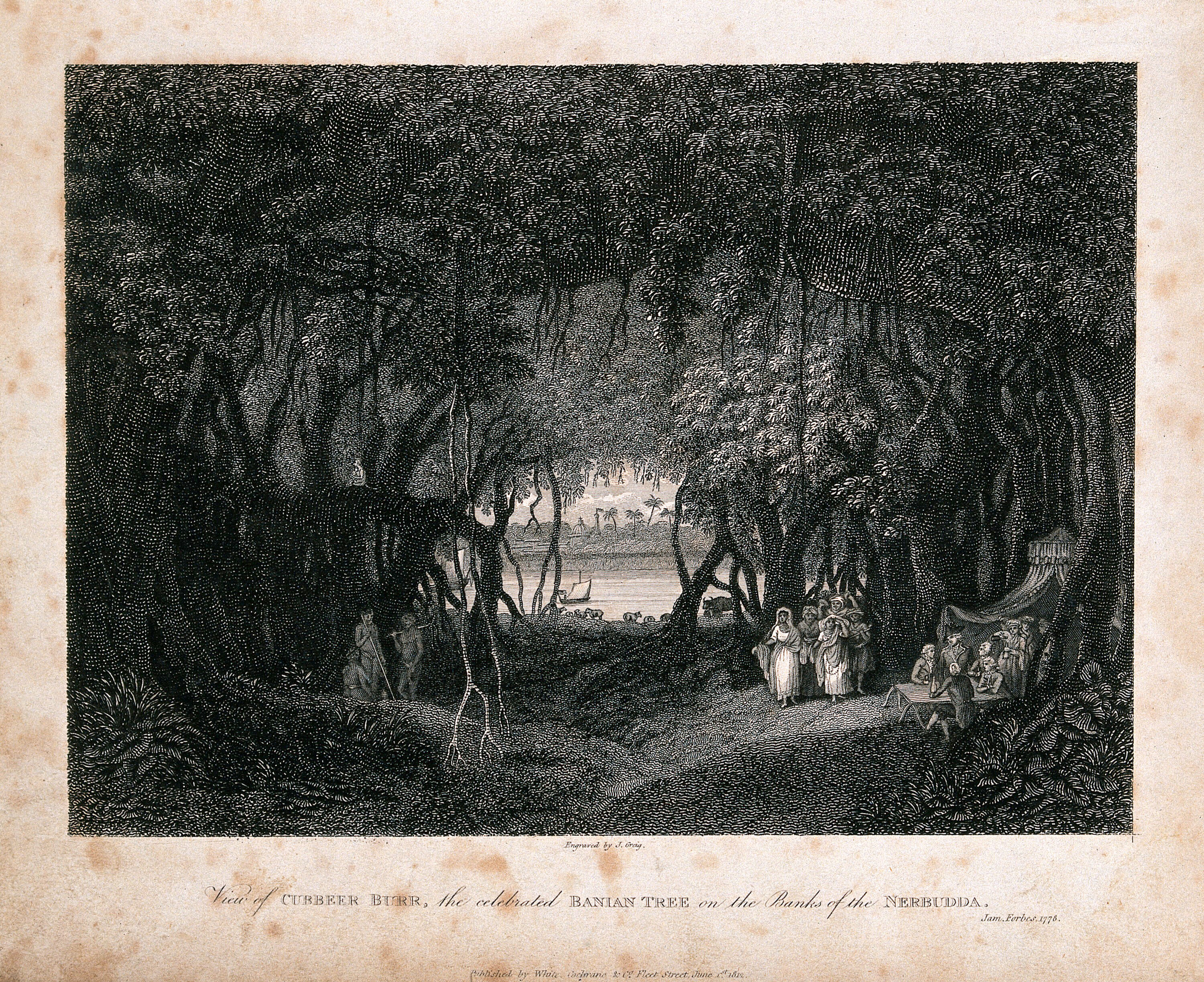

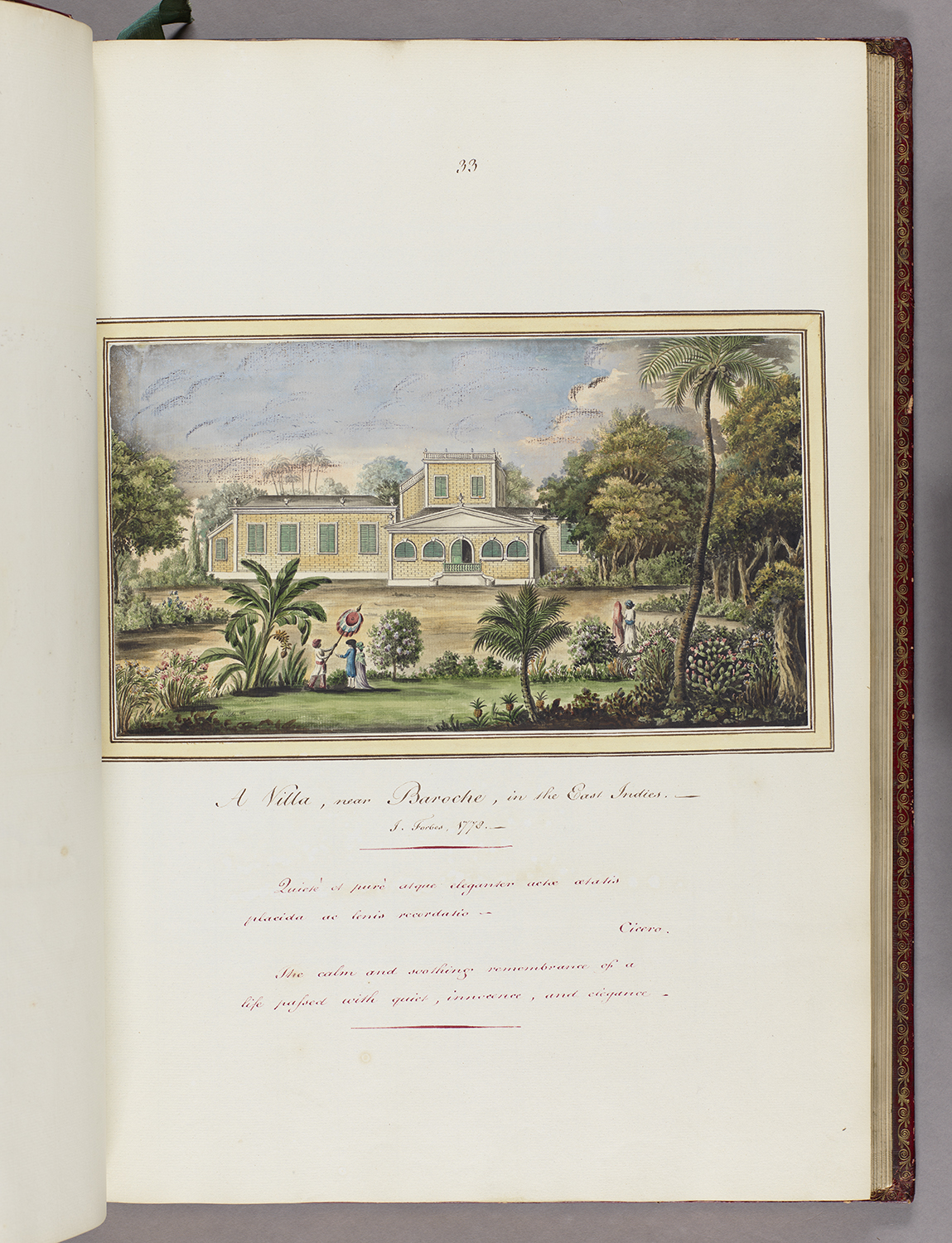

Forbes arrived in India in 1765 aged sixteen as a writer for the East India Company factory in Bombay (Mumbai). He later worked as a chaplain in the army and a revenue collector, remaining in India until 1785.

Forbes amassed a vast archive of letters, drawings and paintings, including works by India and Chinese artists, much of which is now at the Yale Centre for British Art (YCBA) in the United States. Other works are kept in public libraries and private collections in France, India, and in the United Kingdom. Some of Forbes’ later works are held in the Blacker Wood Natural History Collection at McGill University in Canada.

Forbes’ records provide an invaluable record of western India at a time of transition between the Maratha and British empires. Hidden Hands is a collaborative project and the images shown here were chosen by scholars who are working together to research the Forbes archive.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council for funding, to the Bombay Natural History Society and the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya for making this exhibition a reality, and to the Yale Centre for British Art and the Blacker Wood Collection at McGill for providing high-resolution images.

To learn more about an image, click to enlarge it, and click the ⓘ for more information

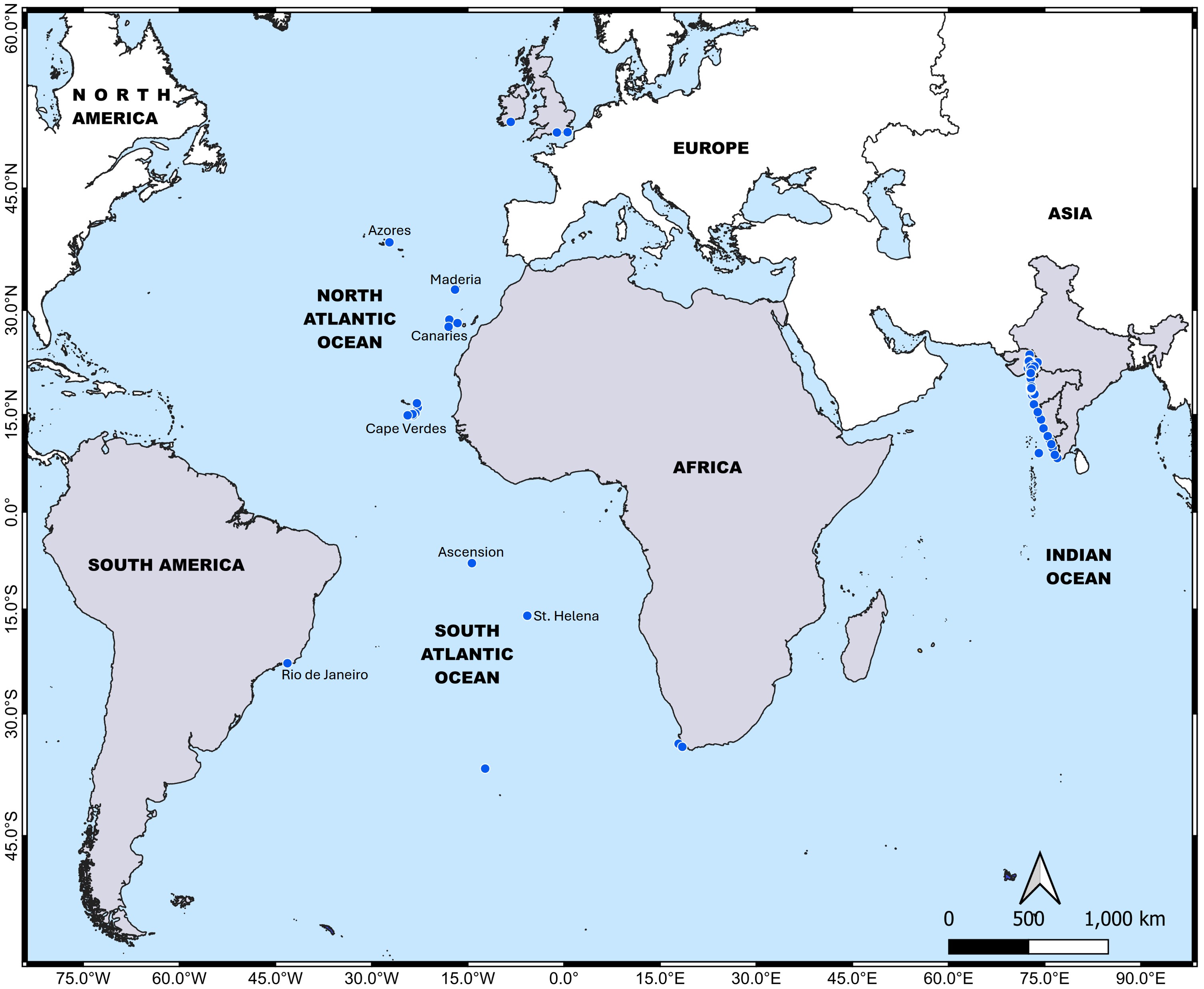

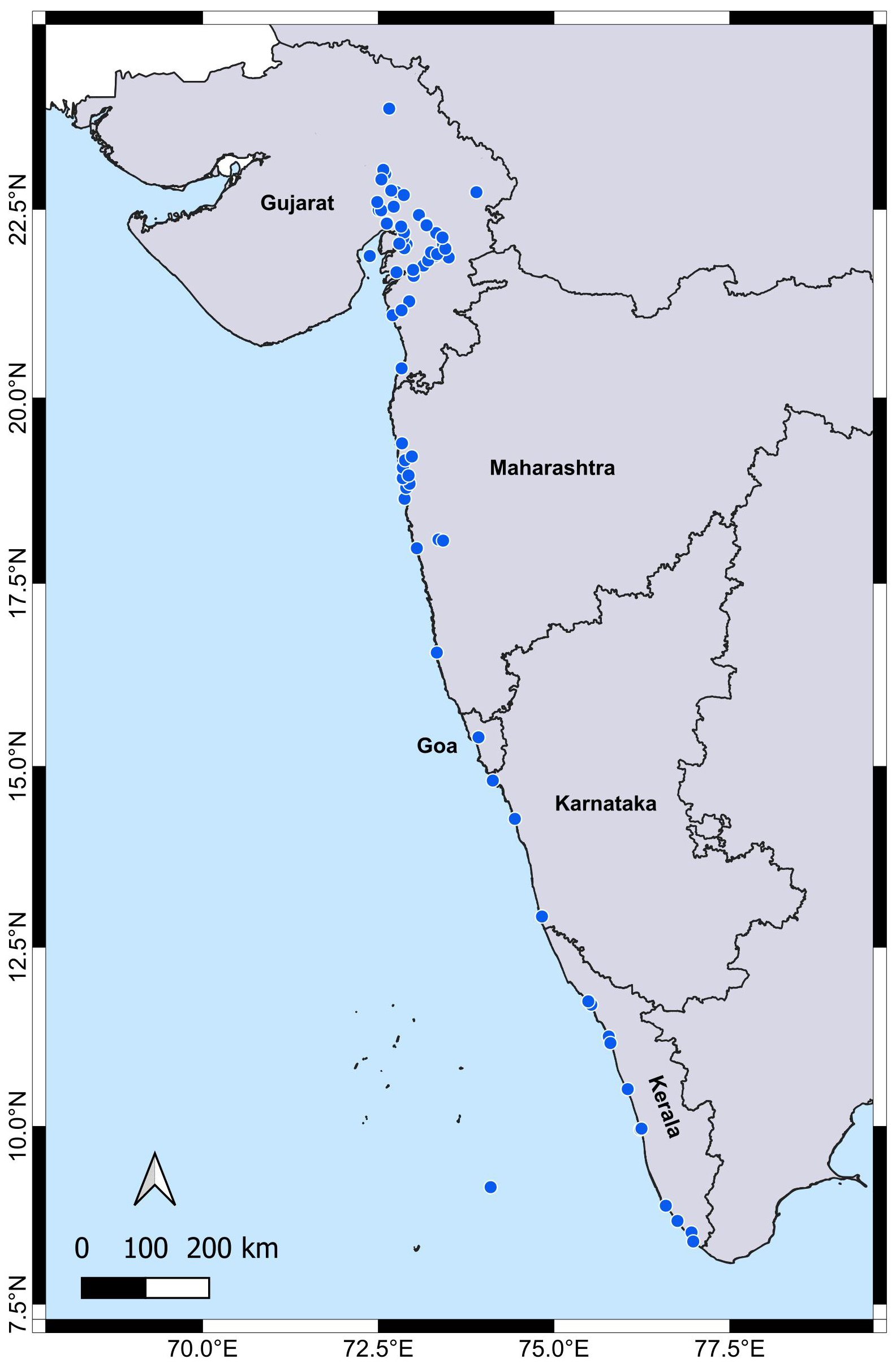

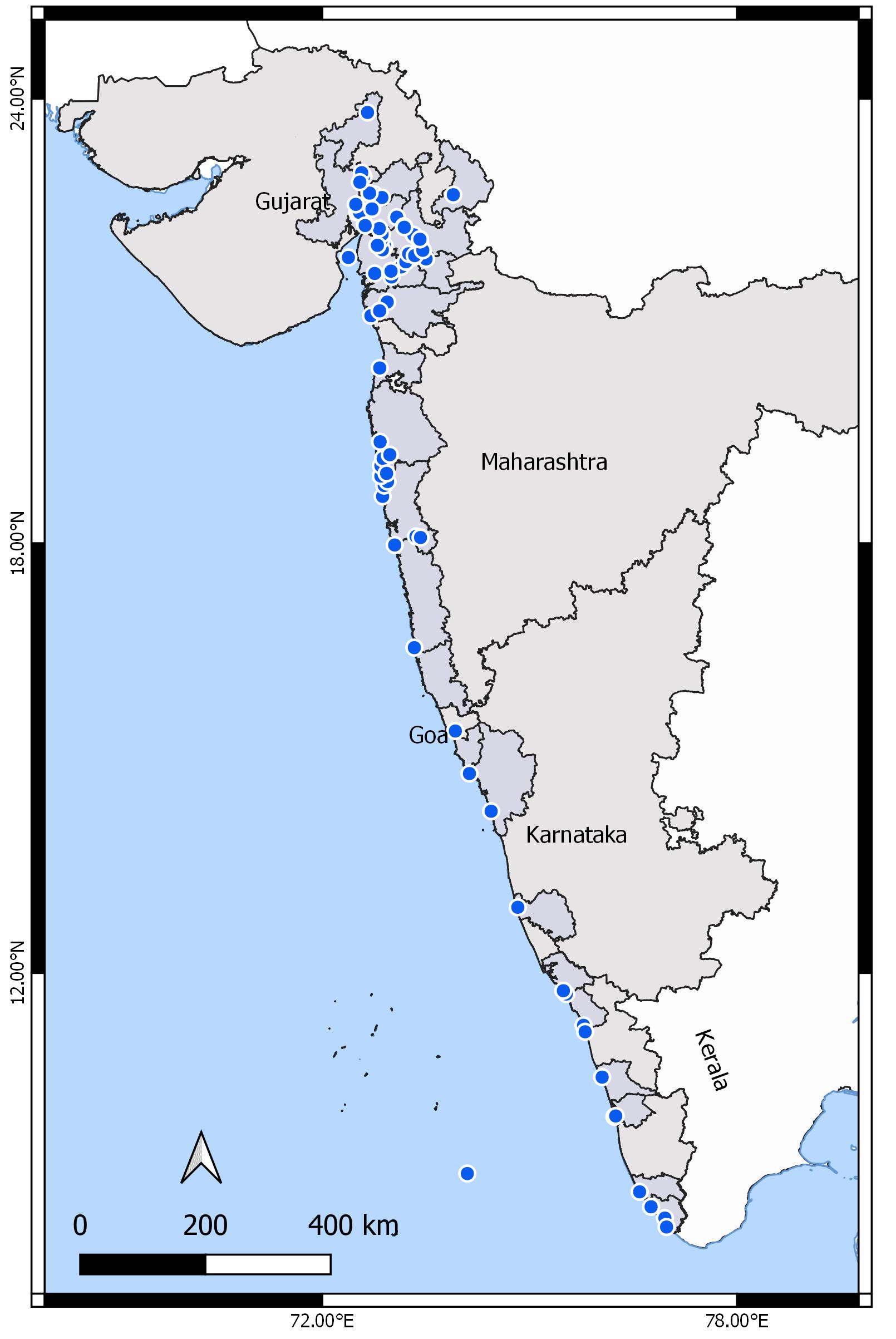

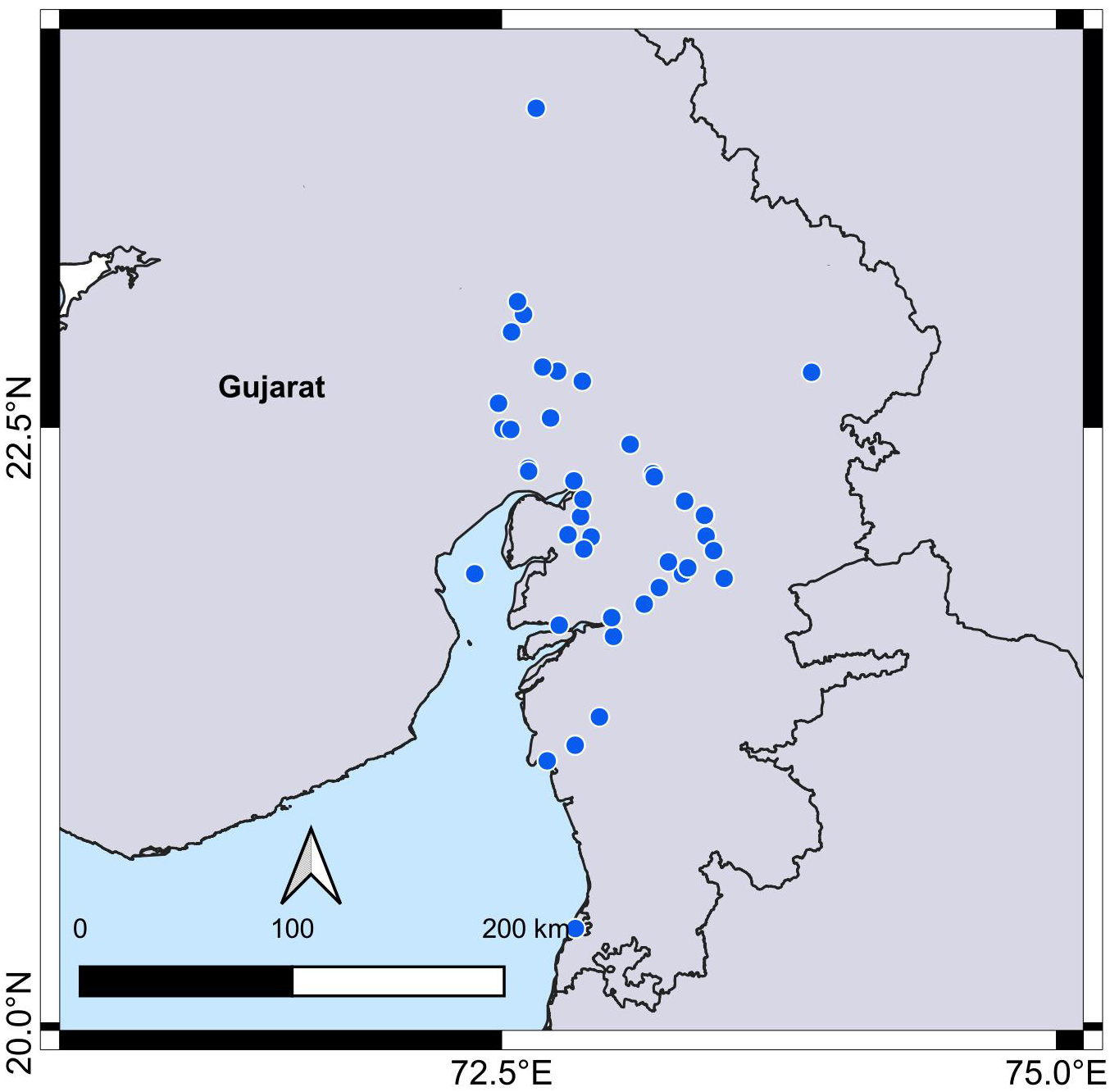

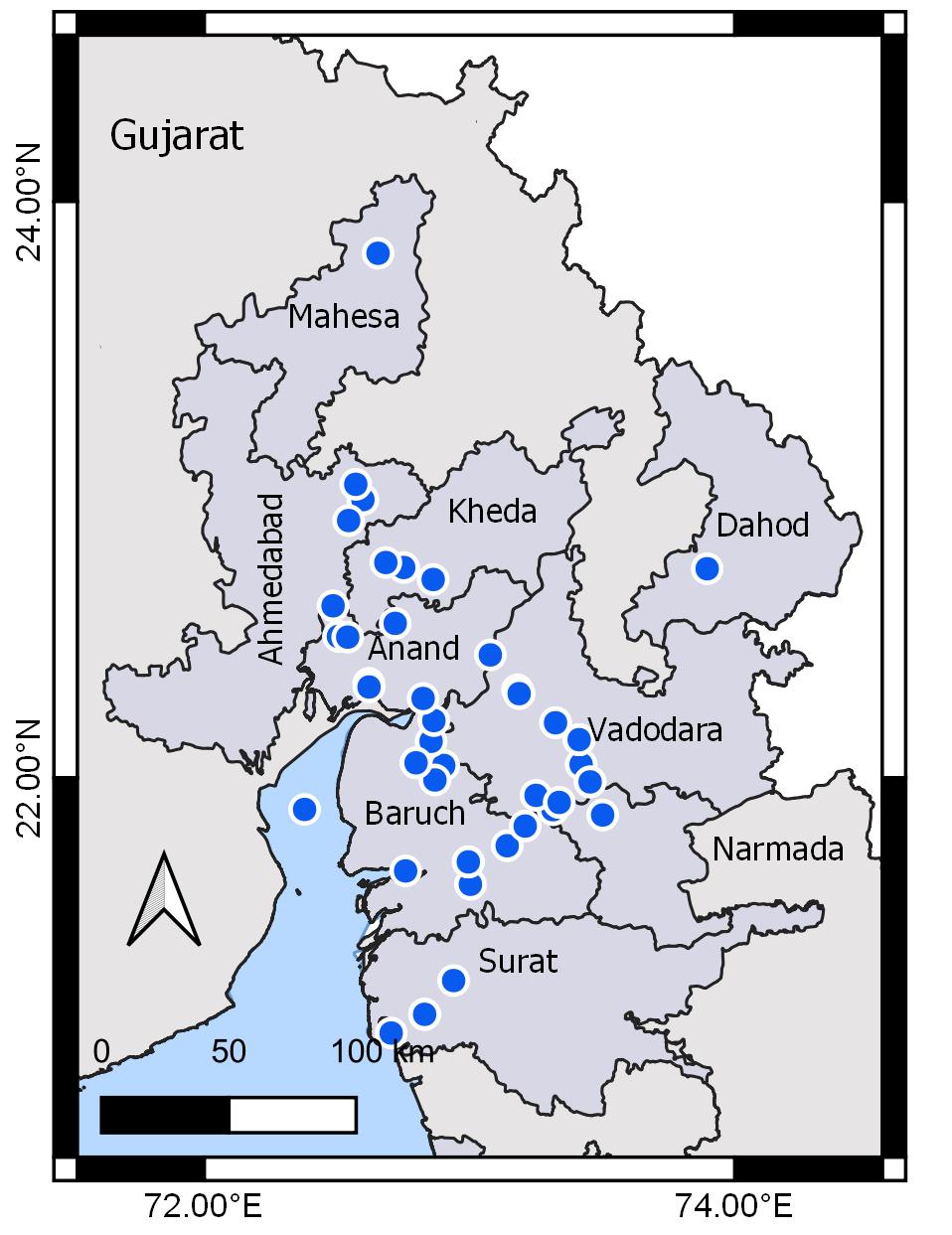

James Forbes: Travel Maps

Credit to S. Subramanya and K.S. Sheshadri

Forbes’ Collage Practice: Techniques and Materials

Written by Madison Clyburn

View Essay

The term ‘collage’ did not describe paper-based mixed media art until the twentieth century when papier collé (glued paper, the only addition to the paper surface) and collage (Fr. coller: to glue or stick, includes anything added to a surface) came into regular use. Before then, terms like ‘mosaic work,’ ‘scrap work,’ ‘adornment,’ ‘découpage,’ and tsugigami 継ぎ紙 (sequenced,1 coupled, or joined) might apply. Other terms like ‘medleys’ and ‘joineriana’ can also refer to mixed-media collage works. Medley making was a form of collage popular in Stuart period England (1603-1714) and considered a genteel practice where English gentlemen cut and pasted printed portraits into historical texts to create bespoke “extra-illustrated” (grangerizing) volumes using varied media like portraits, pamphlets, ballads, playing cards, decorative letters, and old manuscripts. Joineriana refers to processes of compiling fragments into a new and different object like mosaics, shellwork, patchwork, books, and herbaria made from numerous small things in the long eighteenth century.2

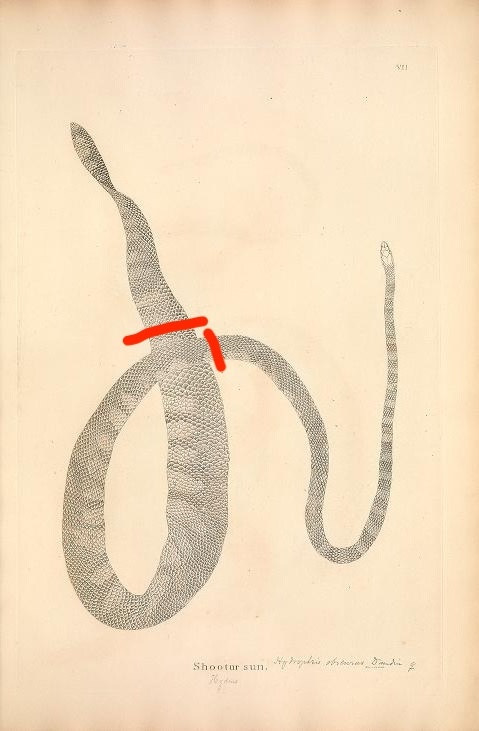

Considering the range of collage techniques, how did a collage artist like Forbes work? What is his process? Forbes’ A Variety in the Shooter Sun offers an ideal opportunity to walk through his particular cut-and-paste process. Many collage artists, like Forbes, used graphite to outline their designs or trace stencil contours before cutting and pasting paper. Some collage artists, like Mary Delany, were said to often cut by sight alone after developing refined technical skills from cutting out landscape and figural silhouettes from an early age—a fashionable creative pursuit in the eighteenth century. But back to Forbes: after Forbes lightly pencilled in his design and two lines at the bottom of the page for the title, he acquired the materials for his subject. In this case, a hand-coloured plate depicting the “Shootur sun” from Russell’s An Account of Indian Serpents and foliage from an unidentified published volume containing botanical prints.

Next, he would need to carefully cut along the contours to remove the desired images from the print, followed by applying adhesive to the back of the cut paper or directly to the paper ground. Forbes likely began with the snake, cutting the body out with two initial cuts using scissors, after which a knife would come in handy to remove the interior space. Once cut out, Forbes could rotate the snake counterclockwise for a landscape orientation. Working piece by piece, he would continue doing the same for the foliage, arranging groups of flowers, leaves, and branches over the snake’s body and gluing them with what is now a honey brown-hued adhesive, which peeks out from various edges of the flowers and leaves. A wash of Indian ink applied within an open space between the upper-left cluster of jasmine blossoms suggests the continuation of the snake’s body, and a patch underneath the snake indicates a soft bed of soil. We are unsure what he would do next as the collage remains unfinished. Perhaps he might add the snake’s head by cutting and pasting the remainder of Russell’s print or fill in the sketched contoured space with gouache and watercolour for the remaining small bits of foliage.

This essay explores some of the different materials involved in collaging, including ones Forbes utilized in his collages, such as paper, pigment, adhesive, and collaging instruments.

Paper

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Dutch papermakers were internationally renowned for their papers’ durability and even surface texture. Technological changes and expanding paper mills meant that French and English papermakers were up and coming.

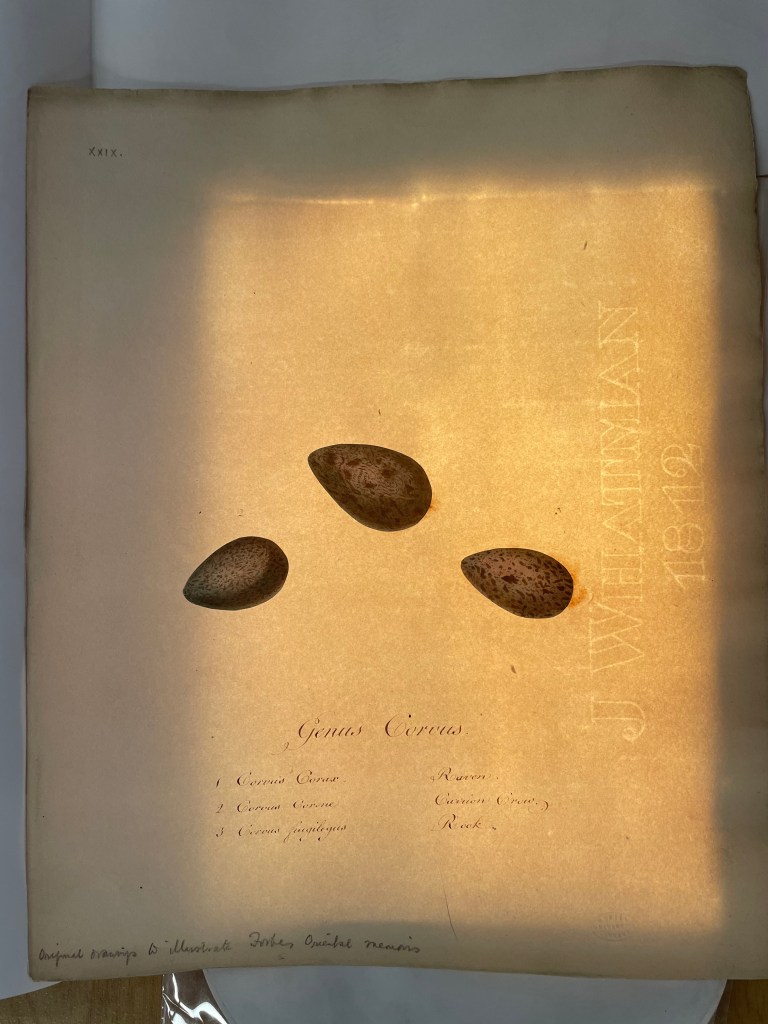

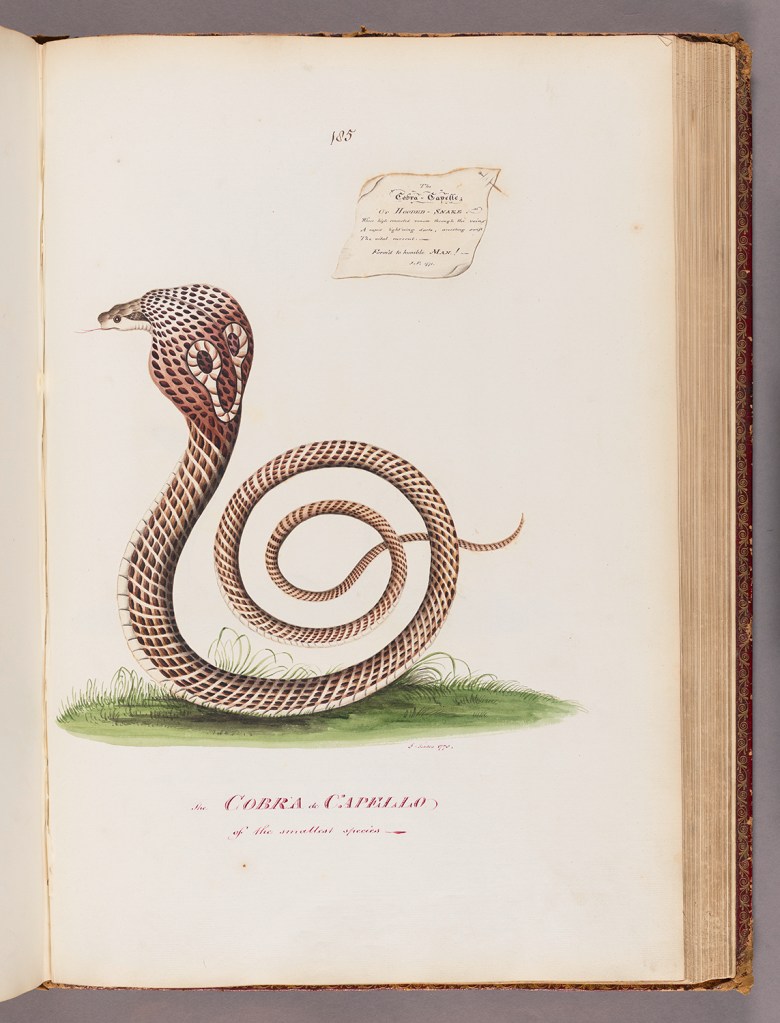

Some of Forbes’ papers include fragments of the Strasburg Lily watermark, used in the 1770s and 1780s: Scorpion, Crocodile, Cobra and pink flowers, Two birds on a branch, Brown bird on white flowering branch, and Two black birds perched on a fruit tree branch, Chameleon. The Lily may be associated with Whatman’s 1777 production. Alternatively, it may be an English imitation of a Dutch watermark or the watermark of a Holland paper maker. It is difficult to narrow down the papers’ source without a complete picture of the watermark or countermark.

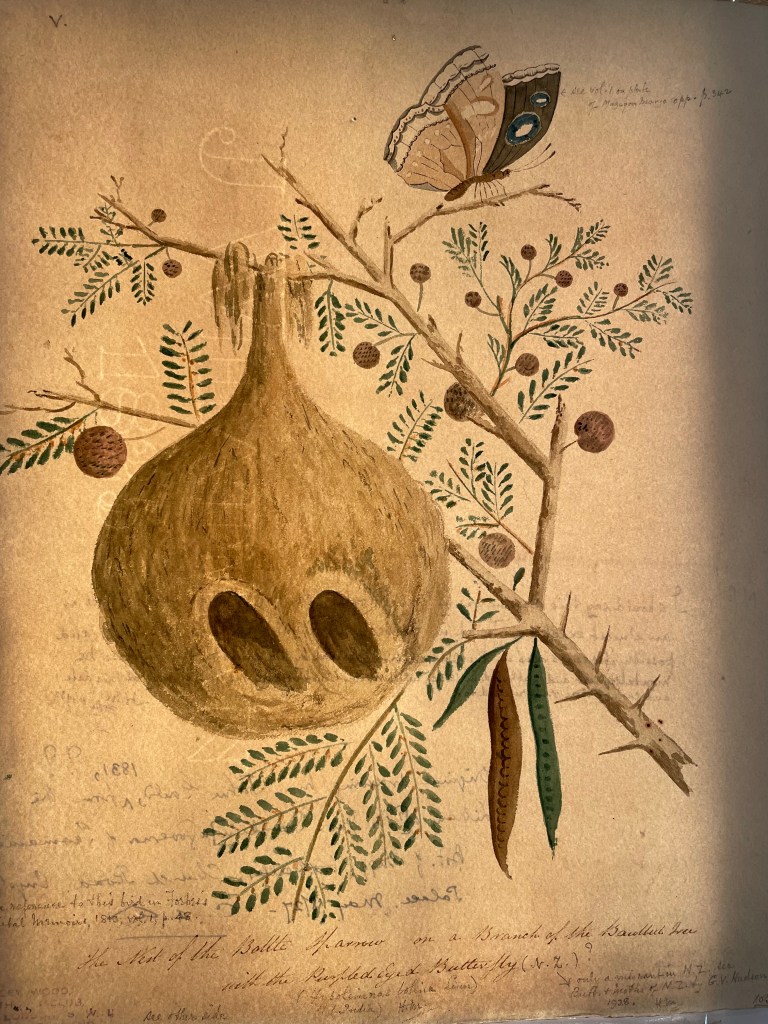

Forbes relied heavily on papers by English papermakers using the Whatman watermark. The watermark on Forbes’ Red-crested cardinal reads “J Whatman 1794.” The Blue-headed bird and moth includes the “J. Whatman 1801” watermark. A Variety in the Shooter Sun, A small specimen of the Cobra Minelle, Genus Scolopax, Genus Meleagris, and Genus Corvus, includes the watermark “J Whatman 1812.” The fragmentary watermarks on Spotted Pardalote and Green and red bird on flowering branch also belong to Whatman from 1812. Coluber Naja includes a watermark that likely reads “J Whatman”; the placement of the cobra and flower blocks most of the mark and any potential date. The watermarks show that Forbes made collages long after returning from India in 1784. Intriguingly, the watermark on The Nest of the Bottle Sparrow identifies its production by Whatman in 1825, six years after Forbes died in 1819! Forbes’ daughter, Elizabeth Rosée Montalembert (née Forbes), likely copied this image in preparation for her edited version of Forbes’ Oriental Memoirs (1834 [1813]).

James Whatman, the Elder (1702-59) began manufacturing paper at “Turkey mill” in 1733. After his death, his widow, Ann Whatman (née Harris), ran the mill until her son, James Whatman the Younger (1741-98), turned 21. Whatman the Younger sold the family paper mill in 1794 to his protegee, William Balston, and the brothers, Thomas Robert and Finch Hollingworth, after he had a stroke.3 By 1804, Balston left the consortium to set up his own paper mill at Eyhorne Street near Hollingbourne. By this time, the Hollingworth brothers had brought another brother into the fold. Both Balston and the Hollingworth brothers shared equal rights to the “J Whatman” watermark. Two other papermakers, Richard Hills and Peter Bower, made forgeries of Whatman’s watermark. Fake Whatman papers were also made in France, Germany, and Austria. So, if Forbes’ papers are indeed authentic examples, then the majority of Forbes’ papers were very likely produced by Balston or the Hollingworth brothers, who maintained Whatman’s watermark, a symbol of excellence.

Whatman papers were imported into India. It is unknown exactly when James Whatman the Younger began supplying the East India Company with paper. Perhaps it was shortly after 1776 when Whatman the Younger re-married Susan Bosanquet (1753-1814), daughter of a Hamburg Merchant and a Director of the East India Company, Jacob Bosanquet (1713-67). Balston and the Hollingworth brothers likely continued to supply the EIC with paper as the new owners. Though Whatman paper was available in India, Forbes very likely purchased Whatman papers closer to home after he returned to England and made the collages in the McGill Archive.

Pigment

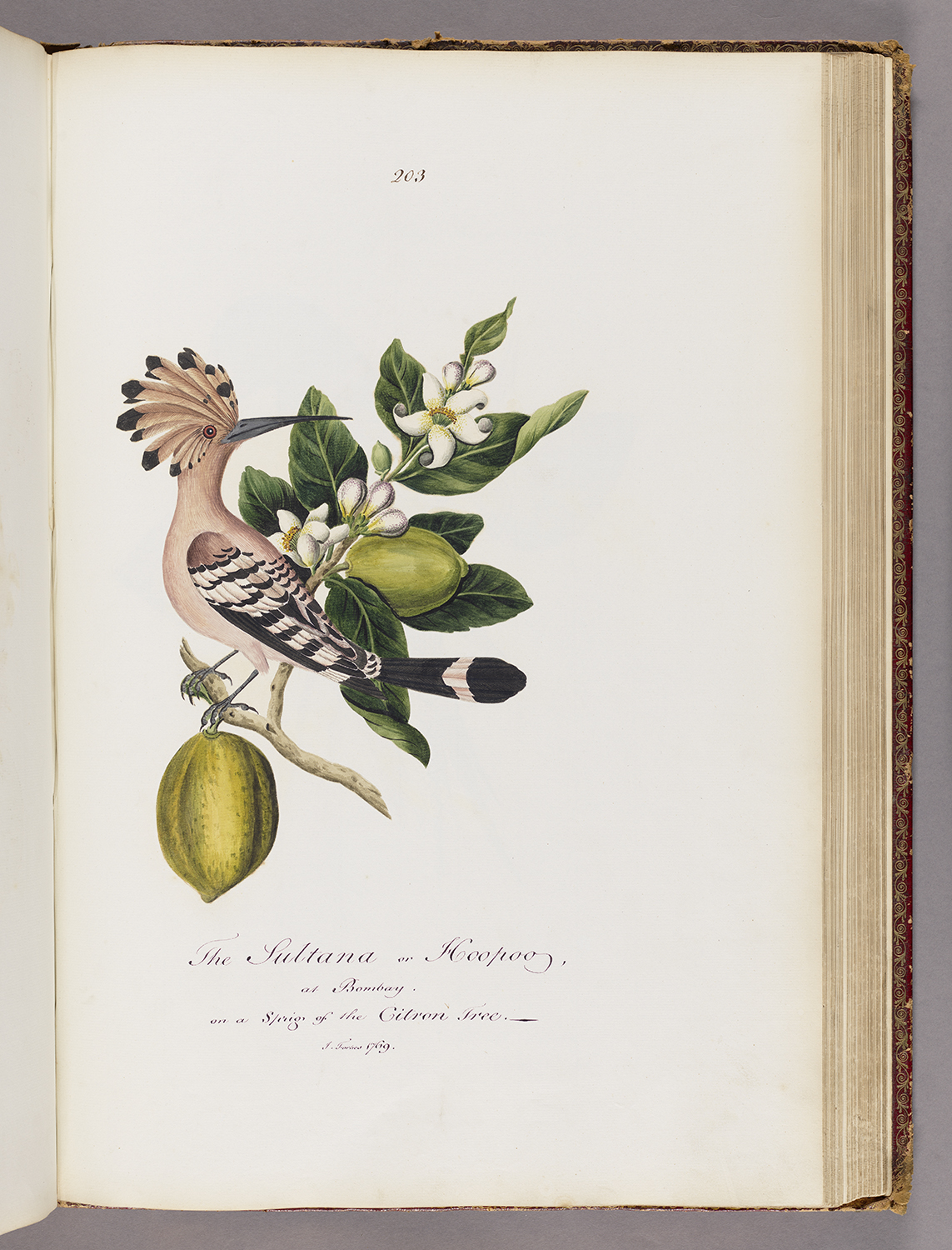

One of Forbes’ imaginatively arranged collage prints depicts a hoopoe poised on a Kamala orange branch next to a butterfly in flight. In this collage, the two paper comlah (Chinese oranges) and leaves, painted with what may be a wash of red-lead, yellow berries, saffron and copper-green, have been pasted onto the surface. The hoopoe, painted in watercolour directly on the paper ground, reflects some of the pigments on hand in the watercolourist’s palette: reds (lake and vermillion) appear in the crest, body contour, wing, and tail feathers with brown shades of umber and lake blended in; lead white and black for the spotted feathers on the wings; and more waterproof Indian ink made from fine black ash like carbon or lamp black mixed with water and a binder on the tips of the crest, throughout the beak and tail feathers.

Another painted image of the hoopoe from Forbes’ manuscript, A voyage from England to Bombay with descriptions in Asia, Africa, and South America, now in the Yale Center for British Art, shows some variation. The brightly articulated Yale hoopoe rests on a sprig of a citron tree, whose pollinated flowers suggest they, too, will produce fruits like those that ripen and hang from the branch conveyed through blends of white, yellow, and green pigments.

Dry-cake watercolours were unavailable until around 1780, when William Reeves invented them and made them available in local shops and for export. They were immediately popular since they saved the artist time previously spent on creating their own colours and because they were easier to keep clean. However, artists made watercolours for personal use before and even after dry watercolour cakes reached the market. To make watercolours, someone needed to grind pigments by hand with a muller (a stone or weight) on a stone or glass slab.4 It was important to reach a “soft” grind; if ground to too fine a point, the individual particles would clump together rather than reduce and dissipate in the water. The sale of crushed paint (peinture broyée) allowed artists to buy individual pigments in specific amounts to create specialized palettes according to need.

Templates offered basic colour suggestions for the amateur or self-taught watercolourist. Manuals, like Art of Drawing and Painting in Water-Colours (London, 1770), suggested that red lead, vermilion, red lake, and carmine were suitable pigments for reds, indigo and ultramarine for blues, sap green and verdigris for greens, and lead white pigment (or flake white) for white paints.5 Yellows were made by crushing gamboge or cutting the roots of barberries and mixing them with a “Lixivium made strong with Water and Pearl-ashes.” Oranges came from layering minium or red lead over a wash of gamboge. Adding water to these pigments produced watercolours. The same pigments mixed with a binder like gum Arabic produced an opaque watercolour called gouache or body colour.

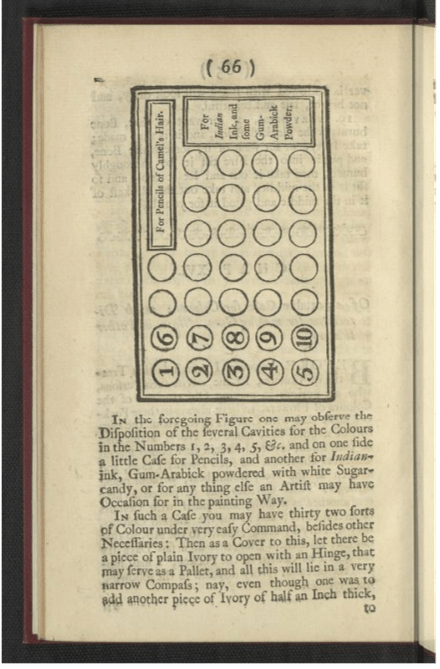

A “portable Case for Colours” about the size of a half-inch-thick ivory snuff box allowed the artist to keep their pigments close to hand. The pocket-size case includes a small reserve for pencils (brushes) made from supple and resilient hairs able to hold their shape against the lightest of pressure. It should also have several concave scoops about a half-inch in diameter and be deep enough without cutting through the ivory base. This case holds up to thirty-two liquid colours, which, after a few days left to air dry, are suitable to carry in one’s pocket in addition to Indian ink, gum Arabic powder and white sugar candy to paste. The artist may attach the watercolour case with a hinge mechanism above an additional case containing drawing instruments.

Adhesive

Many different adhesives were available to artists, like Forbes, practicing collage or cut-and-paste techniques. Animal products, like eggs, cheese, ox gall, bull’s blood, animal hide (rabbit skin was especially popular), and fish bladders were used to make glues. The paper mosaicist Mary Delany promised to send a tried-and-true recipe for “isinglass cement” to her sister Anne D’Ewes (1707-61) as soon as she could consult her book of receipts.6 To make isinglass glue, one should collect the air bladders of some fish, like a sturgeon, then soak the fish’s dried bladder in water to soften it, after which remove the excess water. Next, add fresh water and boil the bladders until they dissolve and the mixture thickens into a loose paste.7 The glue needs to remain warm to achieve a smooth, brushable texture.

A range of vegetable options were also available. Eggwhite was common enough and easily sourced from home. Flour paste was also simple to make since its two ingredients—water and flour—were staples in an eighteenth-century kitchen; simply mix the two ingredients, boil until smooth, then apply it as glue.8 Other, though more costly, kitchen supplies, like sugar, could be used. In France, compact adhesive lozenges called colle à la bouche were made from a compound of equal parts glue and sugar, sometimes with fruit flavouring.9 These lozenges were held in the mouth, allowing the adhesive to stick to the tongue before being applied directly to paper. Since vermin are attracted to the residual animal products used in glues, the value of vegetable glues made from gum Arabic, tragacanth gum, and gums from a plum or cherry tree in gummosis (the release of gum in response to injury), and rock alum, were extolled.10

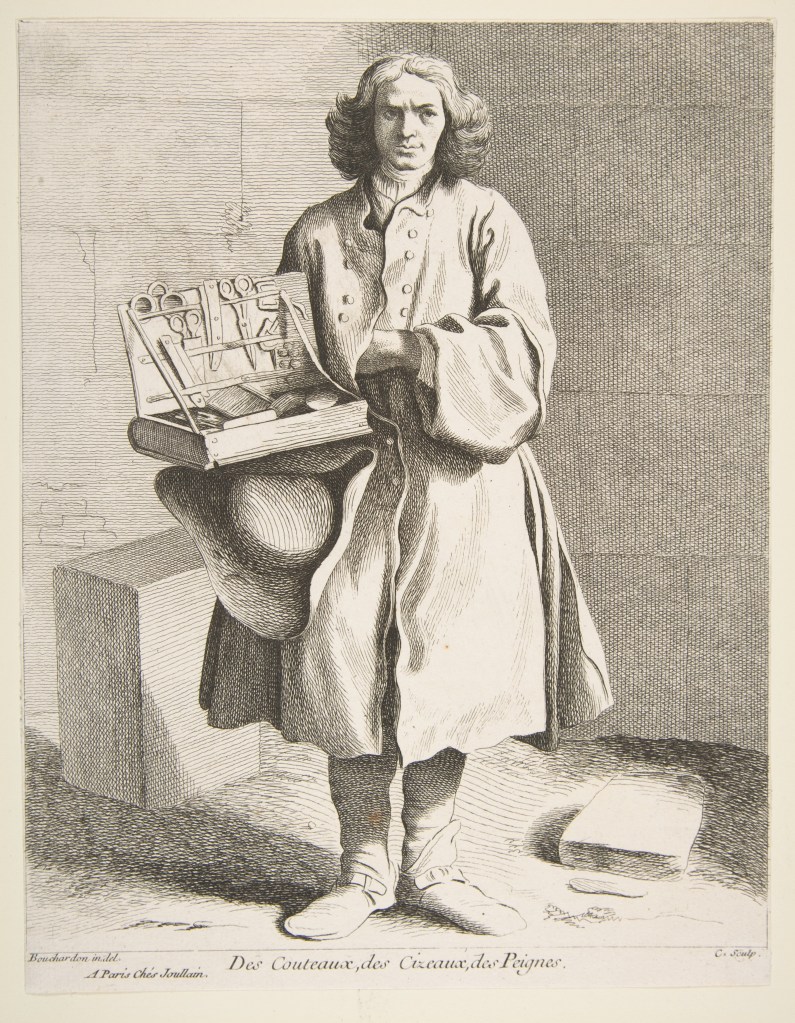

Collaging Instruments

Collaging and drawing instruments were often one and the same, housed in vertical pouches with wood cores and slots for specific tools encased in boiled and embossed leather. Waterproof fish skin, including stingray and sharkskin, was a common material used to encase drawing cases from around the 1700s onward. Silver, tortoiseshell, and shagreen encased wooden cases, but these were more expensive materials. In England, shagreen was a popular finish made from natural shark skin, stingray skin, or leather typically dyed green. Drawing cases from this period were seldom embellished with decorative features on the outside, indicating their practicality in withstanding fluctuating climates as they travelled from city to country across oceans and withstood varying climates.

Artists used compact pocketbooks in addition to vertical or horizontal cases. A pocketbook given by Queen Charlotte to Mrs. Delany in 1781, complete with “a knife, sizars, pencle, rule, compass, [and] bodkin,” was suitable for needlework and making cut-and-paste paper works.11 When Forbes and Mrs. Delany were working, pencils were cedar-encased graphite rods. Sometimes, the reference to a brush or pencil was interchangeable since pencils signified any artist’s brush capable of achieving “delicate effects and a fine line.”12 Scissors cut paper, of course, but a knife, comparable to an exacto knife, could obtain more precise cuts. A bodkin is a sharp, slender tool for making tiny holes in the paper, which is meant to help the artist cut out precise shapes or guide the placement of the many pieces involved in collage works. Once Forbes affixed individual pieces to a paper surface, he might have used a bone folder to smooth any wrinkles. Though not included in Mrs. Delany’s pocketbook, a set of tweezers was also a standard part of the cut-and-paste artist’s ensemble, as it allowed artists to safely pick up tiny, delicate pieces of paper and place them on the paper support without causing damage.

Forbes’ collages are typical of the eighteenth and nineteenth century’s interest in amateur natural history and creative mixed-media practices, especially since Forbes probably intended to share his collages, now in McGill and Yale, with family members rather than for publication. For instance, Forbes dedicates the thirteen-volume Yale manuscript, A voyage from England to Bombay with descriptions in Asia, Africa, and South America, “To [his] Beloved Child, Elizabeth Roseé Forbes, Whose thirst for knowledge, and ardent desire of improvement at an early age, has given an additional pleasure to every hour which was spent on these volumes” on the occasion of her twelfth birthday. The choice of collage as a medium was apt since young Elizabeth Roseé Forbes and other family members could easily sift through the 520 illustrations prepared on light, lap-sized paper decorated with cut-and-paste details, pigment and adhesives.

References

1 Tim Somers, Ephemeral Print Culture in Early Modern England: Sociability, Politics and Collecting (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2021).

2 Freya Gowrley, “‘Joineriana’: The Small Fragments and Parts of Eighteenth-Century Assemblages,” in Small Things in the Eighteenth Century: The Political and Personal Value of the Miniature, eds. Chloe Wigston Smith and Beth Fowkes Tobin, 109-24 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

3 Stephen Hill and James Lloyd, “Springfield Mill,” Kent Archives and Local History, https://www.kentarchives.org.uk/collections/getrecord/GB51_U4062.

4 Marjorie B. Cohn and Rachel Rosenfield, Wash and Gouache: A Study of the Development of the Materials of Watercolor (Cambridge: Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Fogg Art Museum, 1977), 33.

5 N. A., The art of drawing, and painting in water-colours. Wherein the principles of drawing are laid down, after a natural and easy manner; and youth directed in everything that relates to this useful art, according to the practice of the best masters… (London: Printed for J. Peele, 1735), 59-70. https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.rbc/Rosenwald.2464.

6 Mary Delany to Anne Dewes, 26 May 1747, in Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany: with interesting reminiscences of King George the Third and Queen Charlotte, v. 1:2, ed. Right Honourable Lady Llanover, ser. 1, 2:459-461.

7 Kohleen Reeder reconstructed the Booth Grey ‘Geranium Macrorrhisum’ and Delany’s ‘Narcissus Poeticus’ and discusses the process of making isinglass glue in depth. See, Kohleen Reeder, “The ‘Paper Mosaick’ Practice of Mrs. Delany & her Circle,” in Mrs. Delany & Her Circle, ed. Mark Laird and Alicia Weisberg-Roberts (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2009), 233.

8 Reeder, “The ‘Paper Mosaick,’” 232.

9 A. M. Perrot, Manuel du Coloriste (Paris, 1834), 18.

10 Affiches américaines, 7 January, 1767, 131-2.

11 Hayden, Mrs. Delany, quoted in Kohleen Reeder, “The ‘Paper Mosaick’ Practice of Mrs. Delany & her Circle,” in Mrs. Delany & Her Circle, ed. Mark Laird and Alicia Weisberg-Roberts (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2009), 229.

12 Cohn and Rosenfield, Wash and Gouache, 30.

Forbes’ Decorative Ecology at the Intersection of Art and Natural History

Written by Madison Clyburn

View Essay

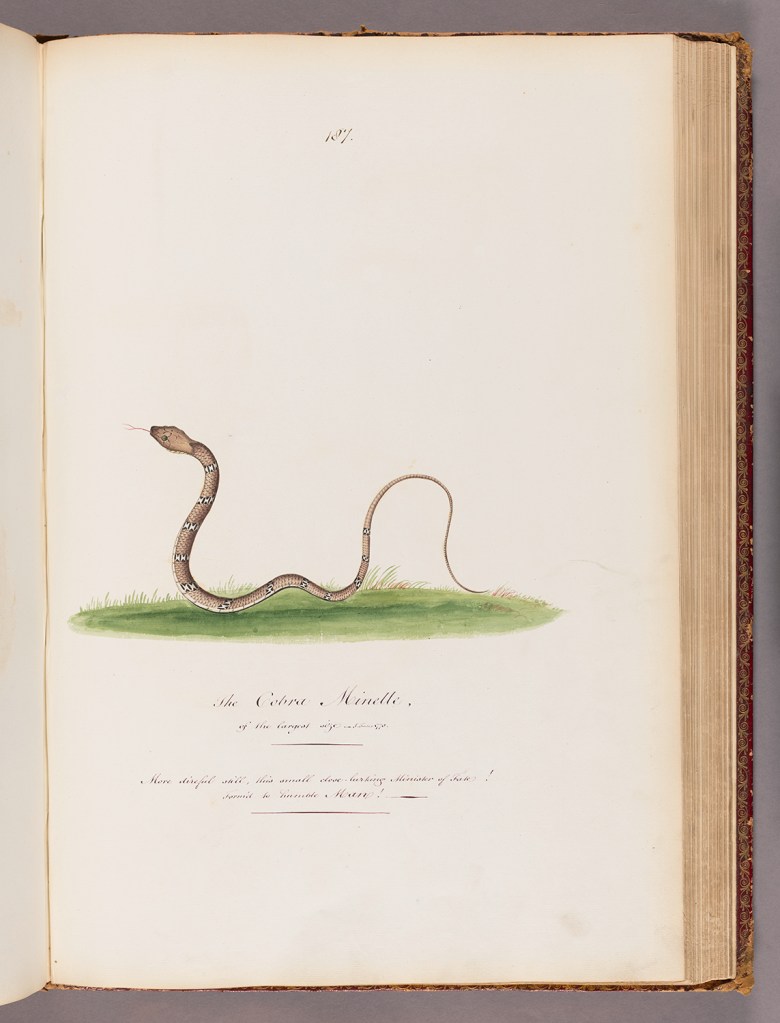

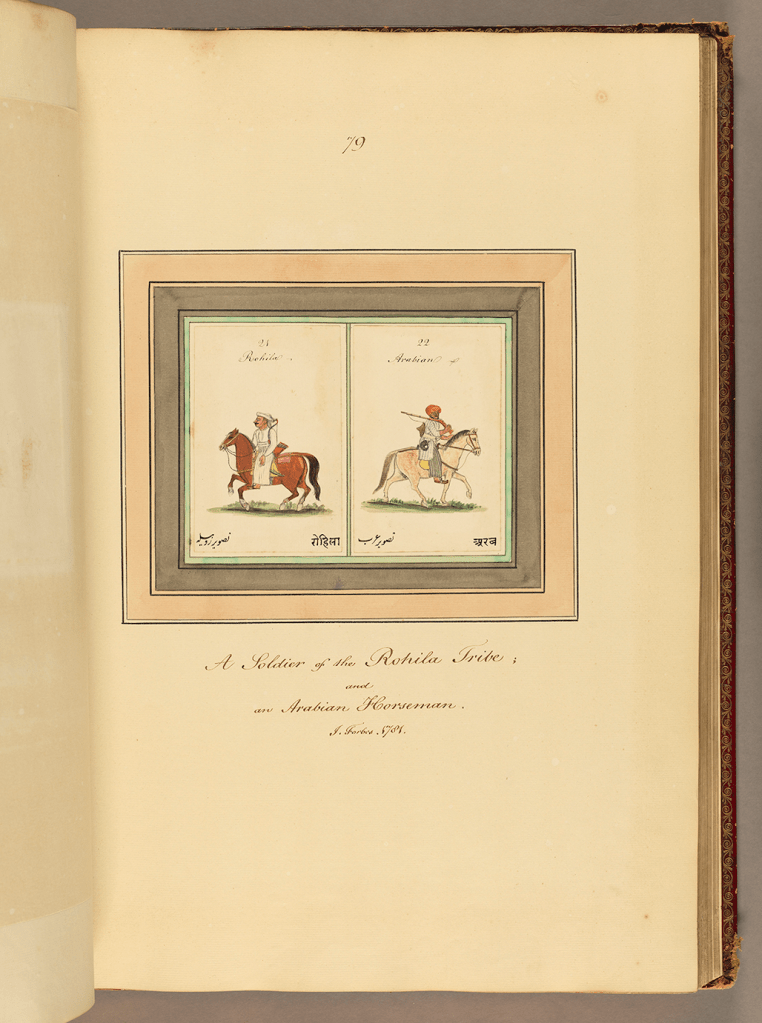

A small specimen of the Cobra Minelle: with the Blossoms and Seed-vessels of the Lagerstroemia Reginae depicts a snake slithering past a six-petalled pink flower (Pride of India). This is an imaginative collage design composed of individually printed natural history illustrations with unfinished details pencilled in. The Cobra Minelle is cut from a plate of Patrick Russell’s (1727-1805) An Account of Indian Serpents, Collected on the Coast of Coromandel (1796-1801). An unacknowledged engraver, presumably William Skelton (1763-1848), made the print due to the inscription, “Skelton omnes fecit,” appearing on the first plate in Volume I of Russell’s text. The foliage originates from a plate titled “Lagerstroemia Reginae” in William Roxburgh’s (1751-1815) Plants of the Coast of Coromandel (1795). Both Russell and Roxburgh’s work was based on original drawings by Indian artists, some of whom were likely Chintz painters, though they never named the artists they commissioned or collaborated with.1

Forbes has cut and pasted Russell’s Cobra Minelle into a new shape by angling the snake’s body to the right, narrowing the space between the midsection of its body and tail and intertwining foliage along the snake’s contour to create a decorative image that initially belies the deadliness of the animal pictured. At times, Forbes also adds literary flourishes to his collages. In Forbes’ 1770 collage of the same snake from his manuscript A Voyage from England to Bombay with Descriptions in Asia, Africa, and South America, Vol. II, now at Yale, Forbes adapts a quote from James Thomson’s (1700-48) poem “Summer” in The Seasons (1730) to describe the Cobra Minelle as “more direful still, this small close-lurking Minister of Fate! Form’d to humble Man!” due to its venomous bite, which occasions a speedy and painful death.2 The 1818 collage in McGill’s collection exemplifies how collage as an artistic medium bridges art and natural history long before its traditional advent in the early twentieth century.

Science and Art: A Long History of Collage

“You ask what is the use of butterflies [and other animals]?” the English naturalist and parson John Ray (1627-1705) asked. Why apparently “to adorn the world and delight the eyes of Man: to brighten the countryside like so many golden jewels. To contemplate their exquisite beauty and variety is to experience the truest pleasure. To gaze inquiringly at such elegance of colour and form designed by the ingenuity of nature and painted by her artist’s pencil is to acknowledge and adore the imprint of the art of God.”3 In the early modern period, artist-scientists and amateur natural historians formed communicative networks that exchanged observations, specimens, and images reflecting the beauty and variety of the natural world around them that Ray speaks of. Some artists collected and raised mammals, birds and insects, others painstakingly observed them from nature, and others still, like Forbes, cut and paste printed natural history illustrations into new artistic compilations.

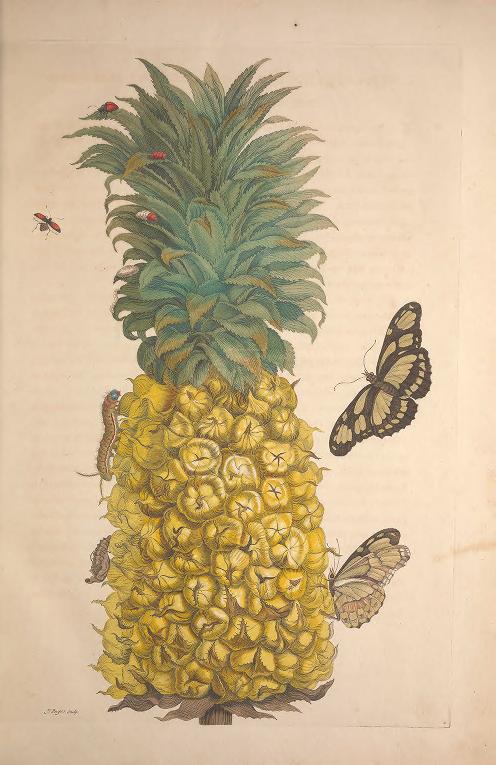

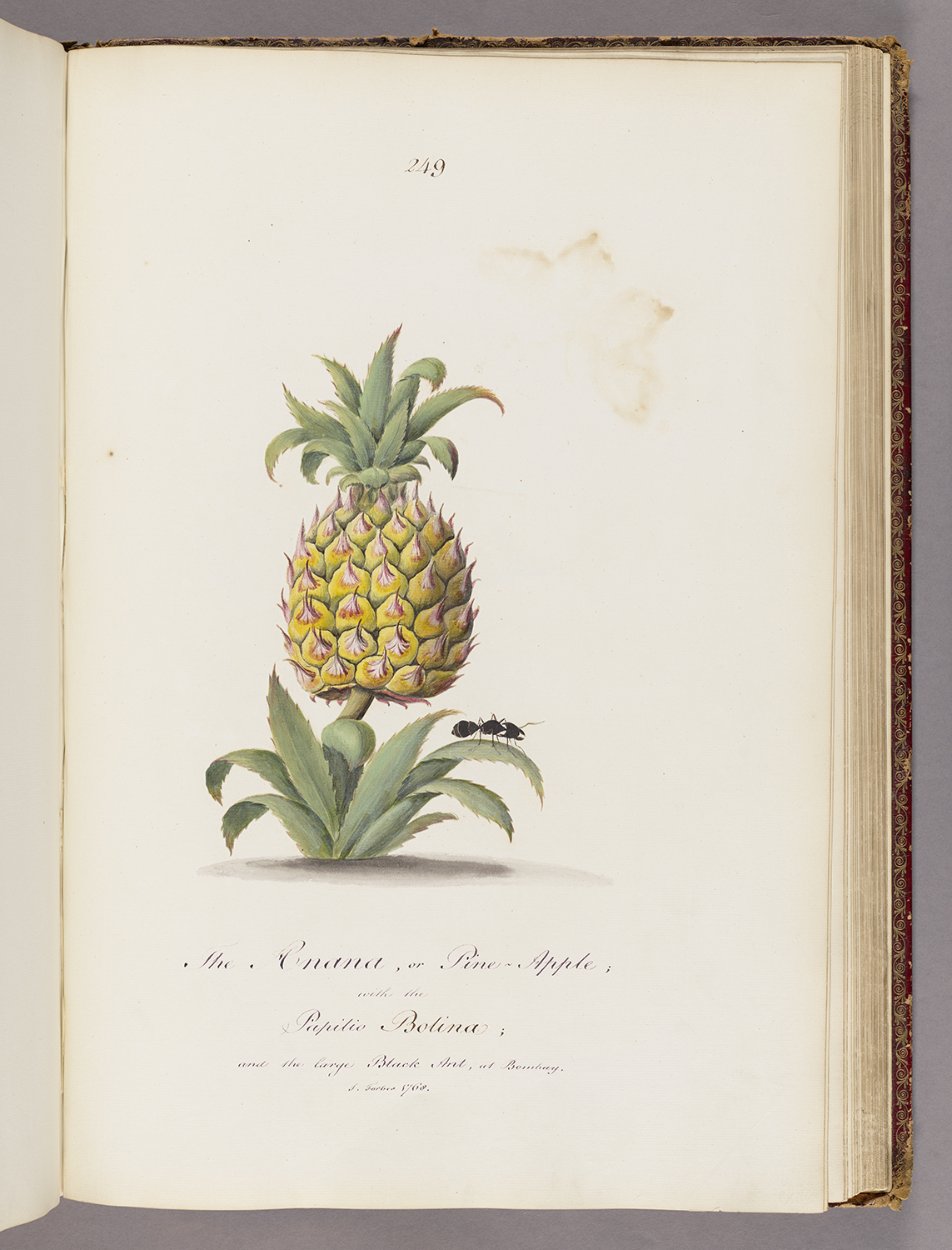

Startingly reminiscent of the naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian’s (1647-1717) pineapple is Forbes’ watercolour of a pineapple adorned with a giant black ant. A cut-out of a butterfly in flight once was affixed to the image. Though only faint traces of the adhesive remain, the butterfly’s fixture on paper would have only strengthened this collage’s nod to Merian’s “Ananas” in her Metamorphosis Insectorum (1705). On and around Merian’s pineapple are caterpillars, butterflies, and cochineal. The two cochineal beetles, shown at rest and in flight, whose red wings are rimmed with black, serve “only to decorate the plate” like Forbes’ missing butterfly and singular ant. Merian’s inclusion of botanical annotations from the naturalists Georg Marcgrave (1610-43/44) and Willem Piso’s (1611-78) Historia naturalis Brasiliae (1648) suggests that just as Forbes took inspiration from Merian, she may have taken inspiration from earlier naturalists.

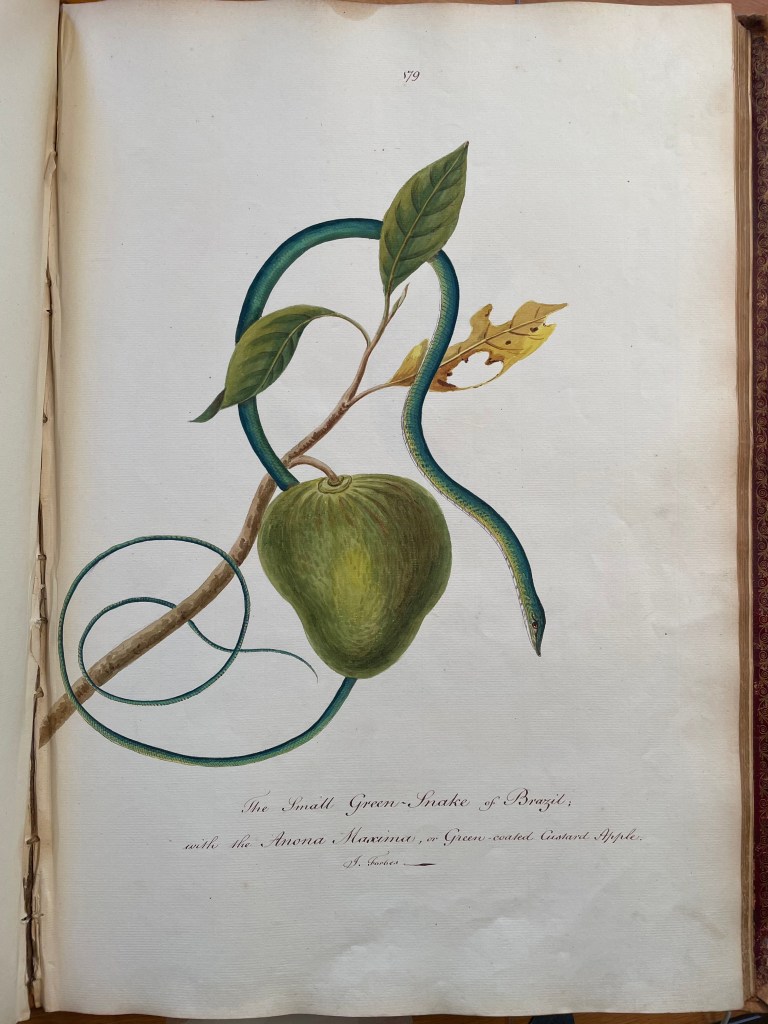

Merian’s illustrations had a lasting impact on eighteenth and nineteenth-century natural history and influenced many later naturalists, including Mark Catesby (1683-1749).4 Catesby combined art and natural history in his visual attempts to document and categorize the natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahamas.5 In turn, Catesby influenced Forbes’s decorative collages. In the example above, Catesby illustrates the harmless blueish-green snake with its distinguished upturned nose as it winds artfully around a sprig of American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana). Forbes’ image of a thin blueish-green snake with an upturned nose from the same genus, if not the same species, appears to miraculously hang from a tree branch, heavy from the custard apple attached. While attentive to the snakes’ pigmentation and scale pattern, the decorative arrangement of both images serves to entice the viewer to follow the snakes as they slither across the page.

The artistic lineage of Maria Sibylla Merian, Mark Catesby, Patrick Russell, and William Roxburgh, and by extension, the unknown Indian artists who drew for Russell and Roxburgh, reproduced or adapted by Forbes, suggests they directly inspired Forbes’ grafted designs. In Forbes’ “grafted” process, he joins materials and inspiration from diverse sources and groups, some of which may have been “violently plundered as well as creatively sutured.”6 The result: an artistic mixture of named and unnamed artists who contributed to creating Forbes’ decorative ecology.

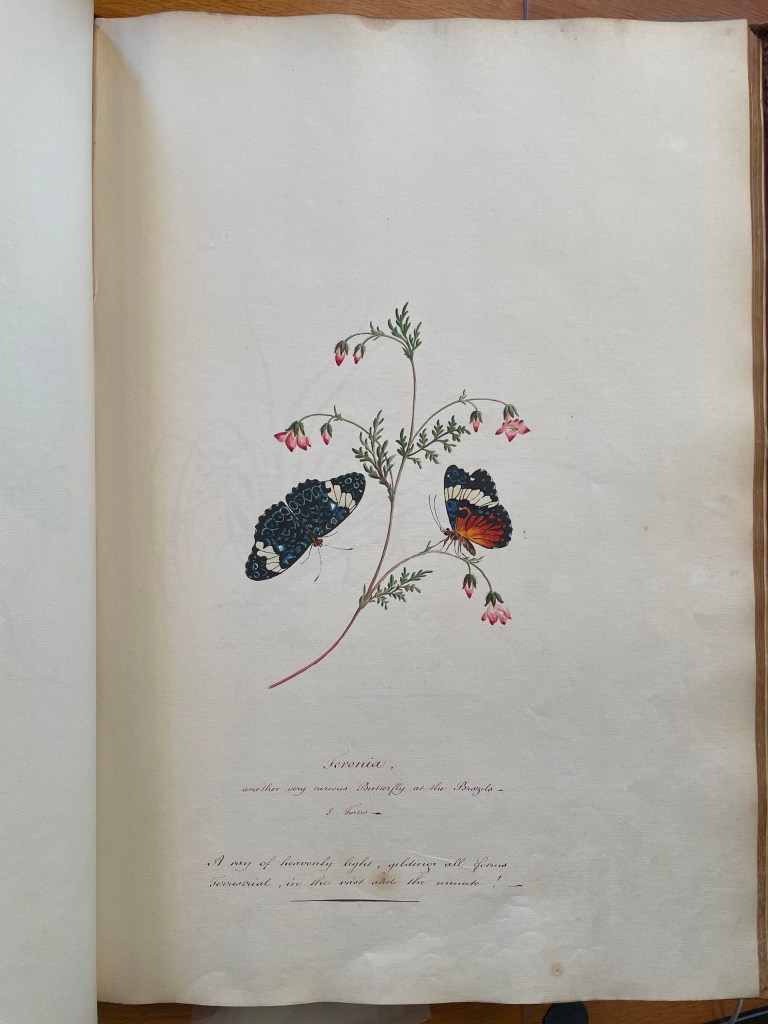

Forbes Decorative Ecology

Forbes’ collages reflect his participation in the fashionable scientific practice of documenting nature, similar to Rene de Rabié [link to butterfly essay]. However, Forbes’ pairing of plants, animals, and verse in his collages evokes a decorative paper ecosystem. The drawing above shows two butterflies near a flowering plant, one with blue, white, and black patterning and one with red, white, and blue patterning. The Latin name Feronia (Hamadryas feronia) is provided. The beginning of a passage from William Cowper’s (1731-1800) “The Task” on the bottom of the page reads, “A ray of heavenly light, gilding all forms terrestrial,” yet another example of Forbes’ literary grafting. The poetic emphasis on ornament—both visual and textual—in many of Forbes’ watercolour paintings and collages lend to what may be called a ‘decorative ecology’ and call for his inclusion in a long line of artists-naturalists who sought to render the natural world on paper ornamentally.

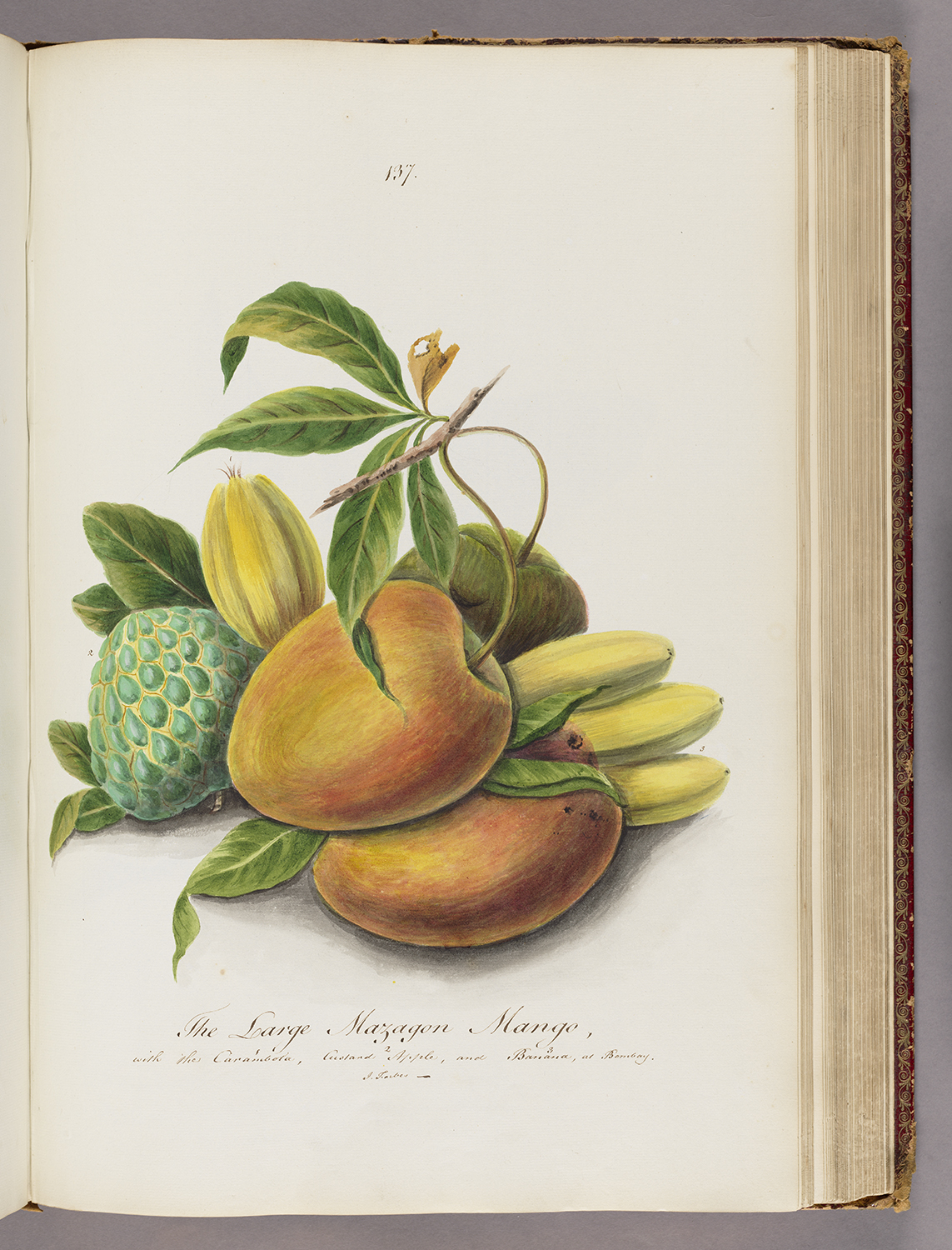

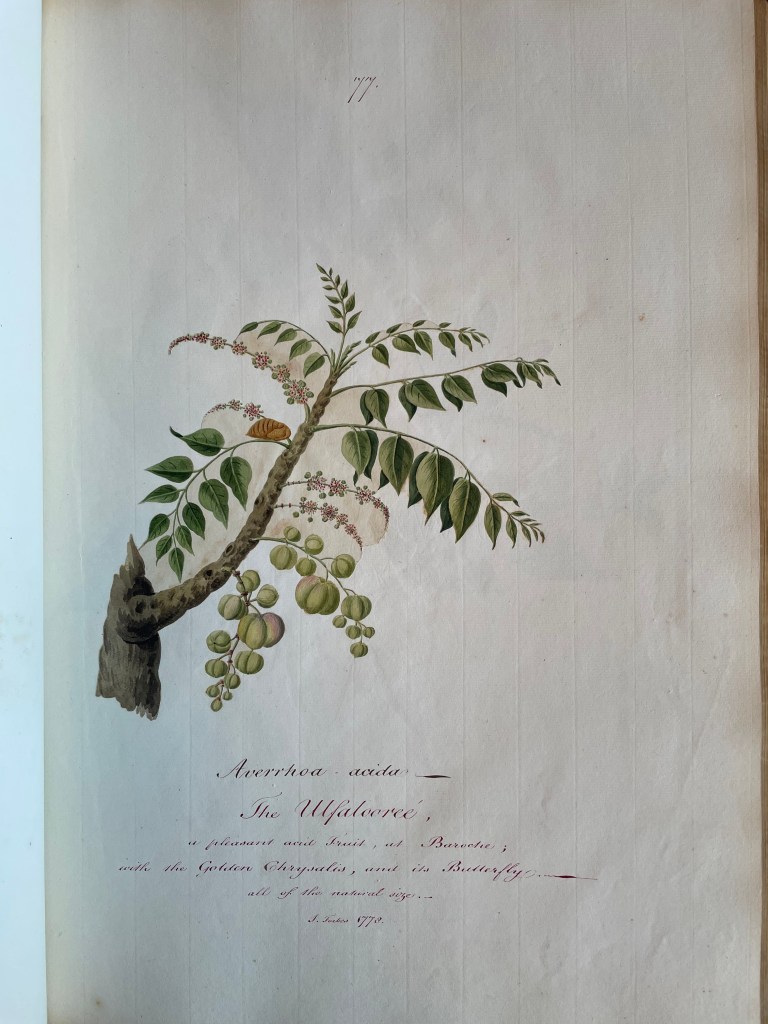

As Forbes describes it via Cowper, the luminous effect of heavenly light conveyed in many of his collages and paintings highlights the pastoral and, at times, dangerous beauty of the natural world seen through his eyes: though Forbes knew the danger involved, he once ornamented his garden at Anjengo (now Anchuthengu) with a pet alligator, at least until it grew too big.7 The Ulfalooree, a pleasant acid Fruit, at Baroche; with the Golden Chrysalis is a collage that shows a gooseberry tree branch (Averrhoa acida; Phyllanthus acidus) with several fronds of leaves and two bunches of fruit. On one of the branches sits a chrysalis painted in gilt gold. This collage is a singular example of Forbes using gold as a medium.

The title suggests it is missing a cut-out butterfly–possibly from Roxburgh, Catesby, or Merian’s publications–which would help to identify the chrysalis precisely. There are a few potential butterflies it may have been: the Common Crow (Euploea core), the Small Tortoiseshell (Aglais urticae) or the Indian Tortoiseshell (Aglais caschmirensis). All three appear in various parts of India and have a silver-gold metallic finish for one week in chrysalid form. Forbes’ collage is likely from the short experimental period when he dedicated himself to practicing the laborious art of Indian miniature painting resplendent in gold. This raises the question: Might Forbes have been inspired by Indian artists who created gilded miniatures?

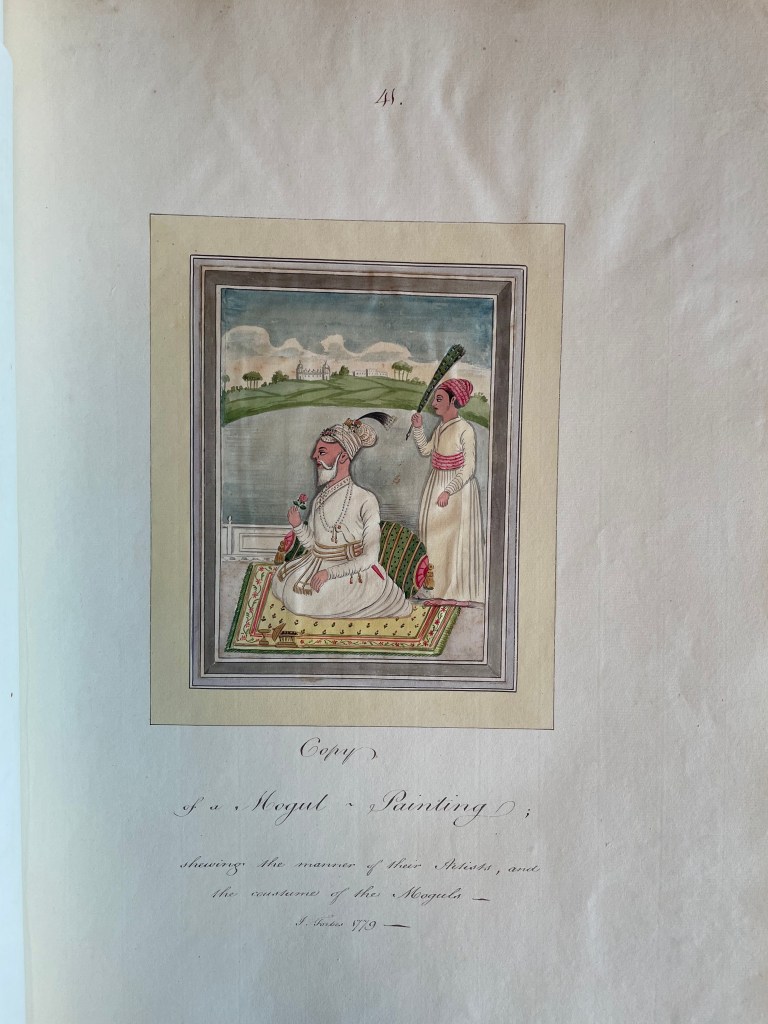

One place to start drawing out the hidden hands that inspired Forbes’ ornamental collages and watercolours is his Copy of a Mogul-Painting (1779), based on an unidentified Indian artist’s miniature. This work is not a collage but a painting, which shows a lavishly dressed man with a Damask rose—the same rose prized for its aromatic oil, rose attar—in his right hand, kneeling on a carpet with a cushion behind him for support. An attendant stands behind him, holding a fan of peacock feathers. Both figures take up the foreground of a terrace; verdant rolling hills interspersed with white buildings surround a silver lake behind them. In addition to signing and dating the work, Forbes included an inscription reading, “Copy of a Mogul-Painting; shewing the manner of their artists, and the coustume of the Moguls.” Forbes collected at least a few examples of Mughal art (discussed in more detail below), including an album of Mughal miniatures created in Delhi around 1750 and 1760 during the reign of Emperor Ahmad Shah (r. 1725-75).

Indian miniature painting flourished from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries, with different regions developing individual styles united by intricate detailing, vibrant hues, and the use of gold leaf. The decline of the Mughal Empire between the early eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries coincided with the East India Company’s growing colonial power and a rising British presence. In this shifting political landscape, earlier illuminated manuscripts and miniature painting albums were sold from princely collections and collected by EIC officials like Forbes. At the same time, contemporary Mughal artists relocated from once-major artistic court centers like Delhi to the provinces of Bengal, Bihar, Calcutta, and Lucknow.

Thus far, the exact Mughal miniature Forbes copied has yet to be identified. Stylistic similarities suggest Forbes may have copied a contemporary Indian artist trained in the Mughal or a regional style, such as Dip Chand or possibly Mihr Chand (no relation), both of whom were active in the mid-eighteenth century. Forbes may have also copied from an unknown painter working after one of these two artists. An example of a miniature by an unknown artist after Dip Chand recalls elements of Forbes’ Copy of a Mogul-Painting in its setting, hues, and perspective, though it is more refined in its attention to detail, blend of pigments and shadowing than Forbes’ copy.8

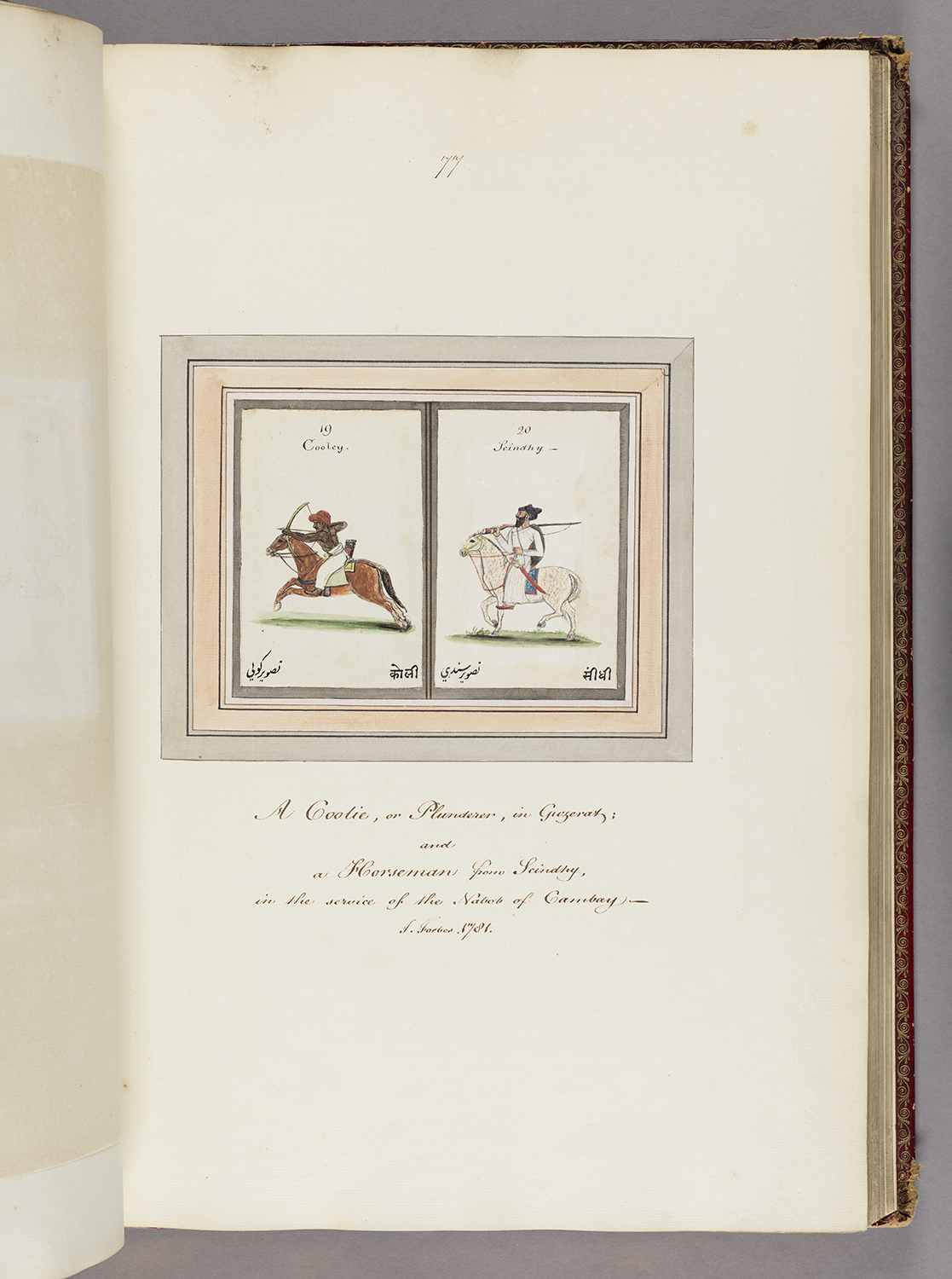

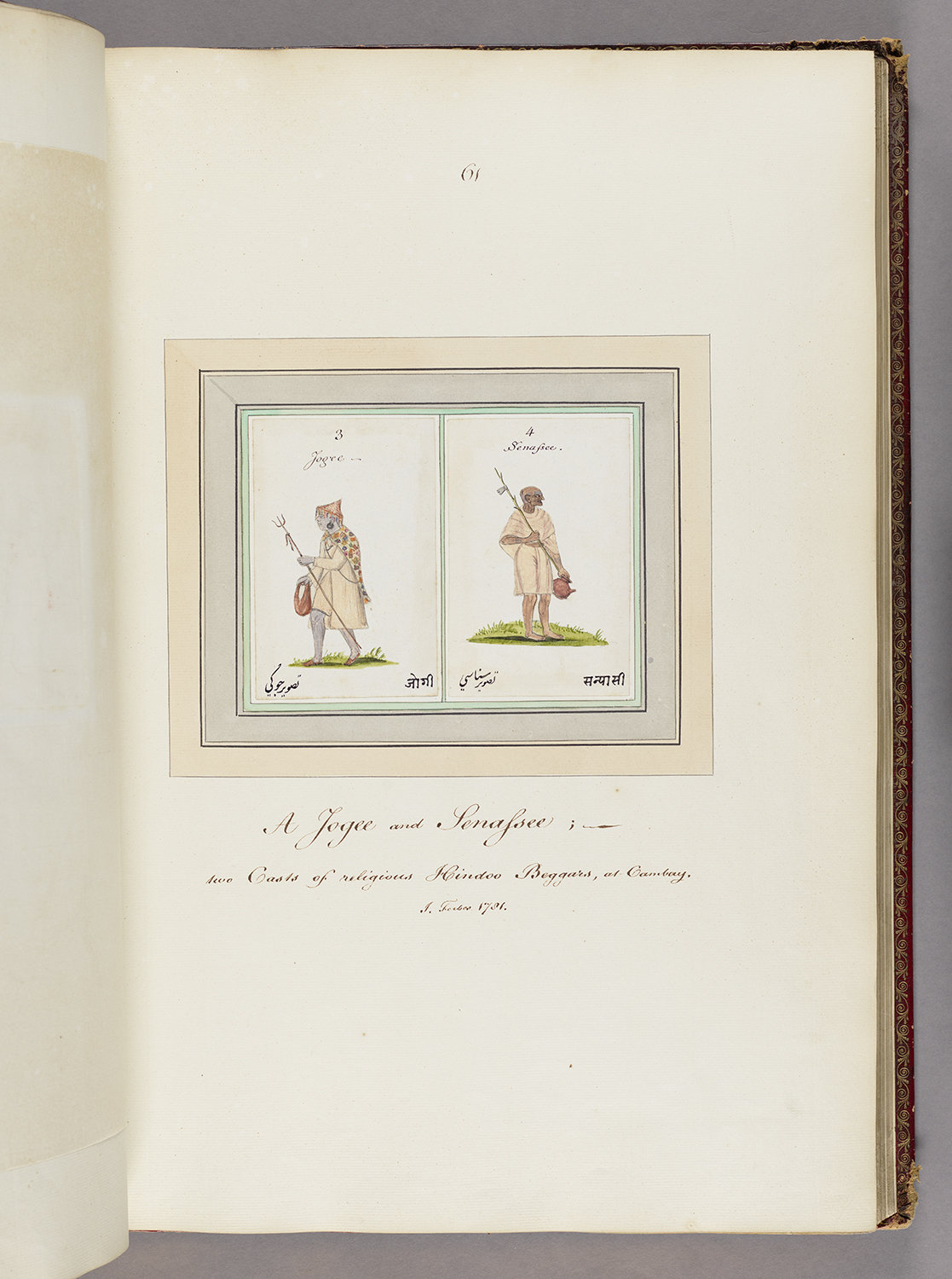

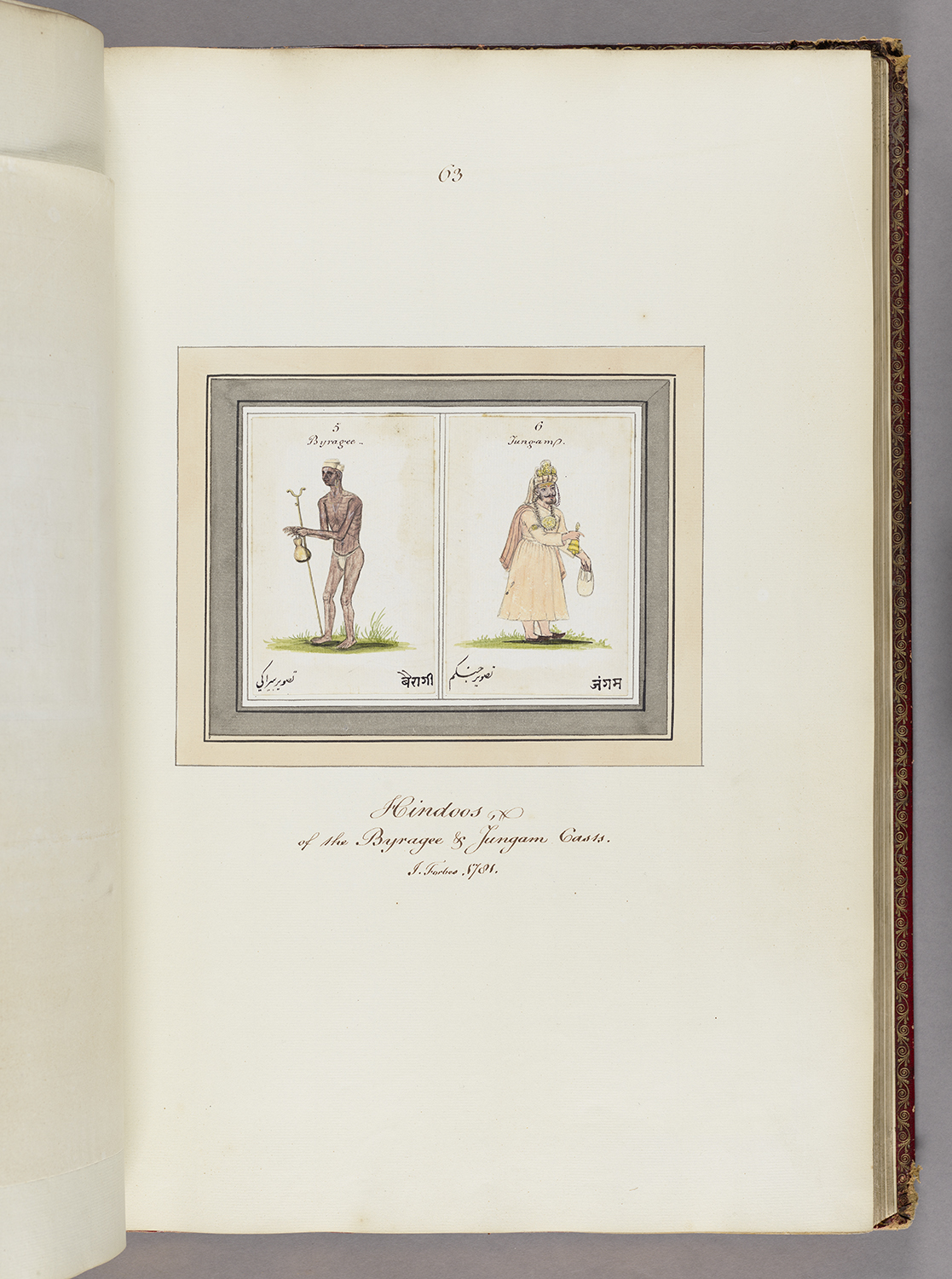

Forbes discusses Indian painting and other art forms in a letter from 1780 November 1, mentioning his attempts to mimic Indian artistic techniques. He concludes that “the style of the Indian artists is hard, incorrect, and devoid of every excellence and grace we admire in the Italian schools,” referring, that is, to the one-dimensional perspective common in early miniatures.9 Six months later, he bought a few original paintings by Indian artists rather than making his own copies—it would appear he gave up on practicing the miniature technique by this point. Forbes describes these paintings as “more curious than beautiful,” again, due to the perspectival difference between Indian and European techniques, the latter of which Forbes is more familiar.10 By May 1781, Forbes began to acquire more Indian paintings and drawings from a certain Brahmin–probably Sadānand Vyās (active late 18th century)–“a man of genius, taste, and extensive reading,” who acted as an art dealer to Forbes.11 Vyās painted the series of eight portraits depicting religious mendicants around Cambay that Forbes commissioned in 1781. His drawings provided Company officials with a “visual dictionary… to identify Indian groups or persons perceived as informants, threats or combatants.”12 Additionally, Vyās worked with Charles Mallet, an EIC resident at Poona (today Pune) and William Holford, an EIC resident at Cambay, drawing detailed maps of Gujarat.13

Whether inspired indirectly or directly by other artist-naturalists, many of Forbes’ illustrations of snakes, pineapples, ants, and butterflies created from watercolour, gold, and cut-and-paste paper highlight his decorative ecology at the intersection of art and natural history.

References

1 Henry J. Noltie, “Moochies, Gudigars, and other Chitrakars: Their Contribution to 19th-Century Botanical Art and Science,” in The Weight of a Petal: Ars Botanica, ed. Sita Reddy (Mumbai: The Marg Foundation, 2018), 42.

2 James Forbes, The Cobra Minelle, of the largest size, 1770, from A voyage from England to Bombay with descriptions in Asia, Africa, and South America, Vol. II, 187, Yale Center for British Art (hereafter YCBA), Folio A 2023 69.

3 Charles E. Raven, John Ray, Naturalist: His Life and Works (Cambridge 1950), 407.

4 For contemporary female naturalists, see Fernanda Mariath and Leopoldo C. Baratto, “Female Naturalists and the Patterns of Suppression of Women Scientists in History: The Example of Maria Sibylla Merian and her Contributions about Useful Plants,” Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 19, no. 17 (2023): 1-29.

5 Henrietta McBurney, “The Influence of Maria Sibylla Merian’s Work on the Art and Science of Mark Catesby,” in Maria Sibylla Merian: Changing the Nature of Art and Science, ed. Bert van de Roemer et al. (Tielt: Lannoo, 2022), 195-205.

6 Holly Shaffer, Grafted Arts: Art Making and Taking in the Struggle for Western India: 1760-1910 (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2022), 3-10.

7 James Forbes letter, Anjengo, 1772 November 15, copied between 1794-1800, Vol. 6, ff. 65-79, YCBA.

8 For other similar works, see Style of Dip Chand, Shah Alam II Seated on a Throne Overlooking a River, c. 1764, gouache and gold on paper, 19.5 x 14.7 cm, Murshidabad, British Library, London, Add.Or.5694.

9 James Forbes letter, Chandode, 1780 November 1, copied between 1794-1800, Vol. 11, ff. 109-118, YCBA.

10 James Forbes letter, Ahmed-abad, 1781 May 7, copied between 1794-1800, Vol. 11, f. 240, YCBA.

11 James Forbes letter, Cambay, 1781 May 12, copied between 1794-1800, Vol. 11, ff. 285-295, YCBA.

12 Shaffer, Grafted Arts, 90-91.

13 Samira Sheikh, “A Gujarati Map and Pilot Book of the Indian Ocean, c.1750,” Imago Mundi 61, no. 1 (2009): 75.

Forbes’ Ornamental Feather Art: Nature Printing as Collage

Written by Madison Clyburn

View Essay

George Braque’s (1882-1963) collage, Still Life with Fruit Dish and Glass (1912), has traditionally been hailed as the advent of the collage technique. Before then, collage as a technique was designated as a popular pastime to practice a leisurely pursuit and process and organize knowledge.1 A series of collaged papers from the Nishi Honganji Anthology of the Thirty-Six Poets (Nishi Honganji-bon Sanjūrokunin kashū 西本願寺本三十六人家集) compiled by the eleventh-century scholar, editor, and critic Fujiwara no Kintō 藤原公任 (966–1041) calls for a much earlier origin of collage art beginning not with Braque and the twentieth-century European Cubism movement but in twelfth-century Japan.2 This alternative history encourages a more inclusive study of collage works, including the varied media and techniques used in eighteenth and nineteenth-century “nature printing,” like animal feathers, wings, and skins.

Featherwork: A Timeless Practice

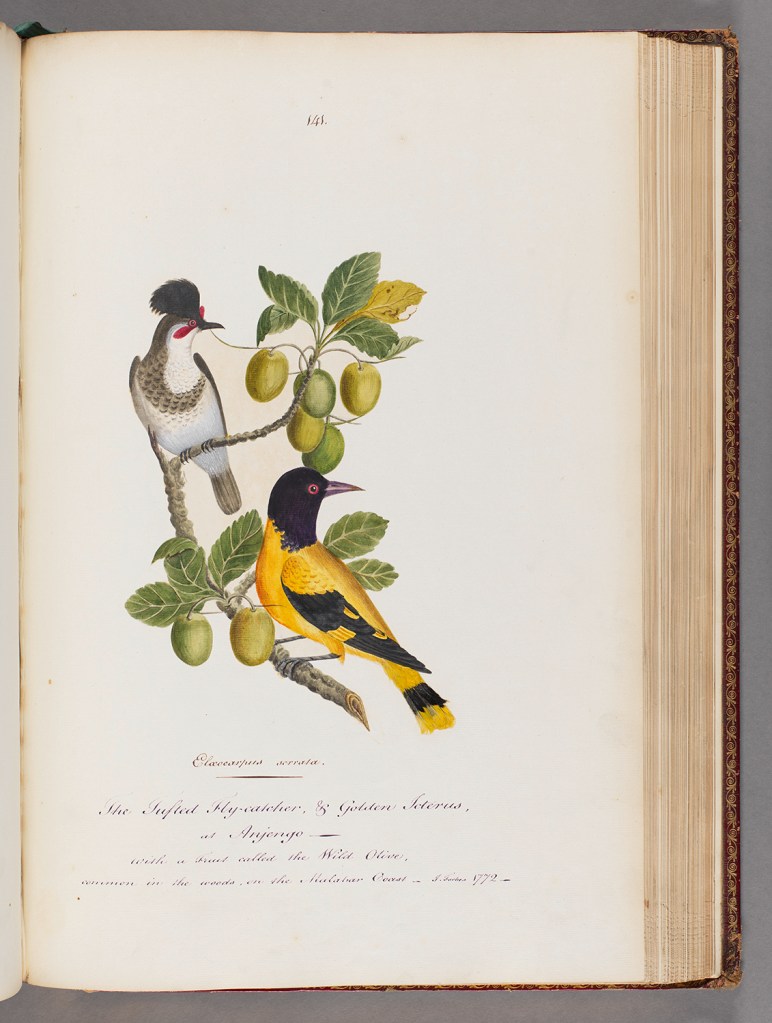

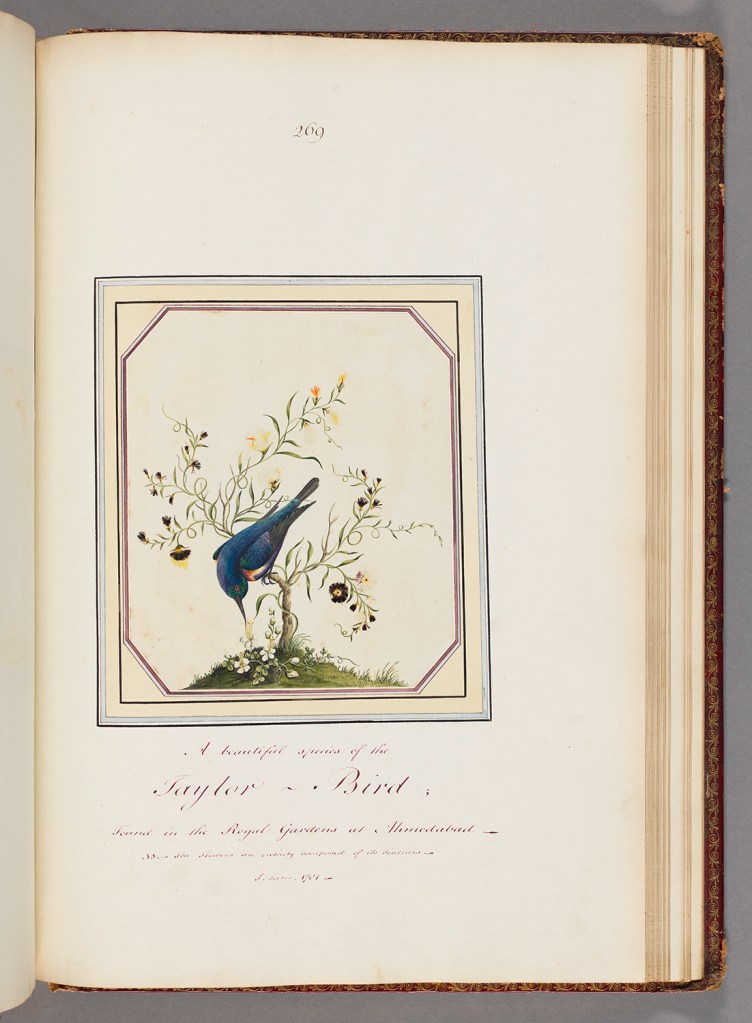

Amid Forbes’ portraits, expansive landscapes and depictions of birds, snakes, and insects are two collages that stand out. The Tufted Fly-catcher, & Golden Icterus, at Anjengo, with a Fruit called the Wild Olive, common in the woods, on the Malabar Coast, shows two birds of different species sitting on a branch of a Ceylon olive tree (Eloeocarpus serrata). The tail of the Golden Icterus on the lower branch is made entirely of yellow and black feathers. A beautiful species of the Taylor-Bird found in the Royal Gardens at Ahmedabad also includes bird feathers. In this image, the flowers are composed entirely of minutely cut blue, purple, and orange feathers affixed to the paper surface with glue. While Forbes’ feather works are curious and precise, they are not innovative.

For centuries, people have made featherworks—often instilled with spiritual power—to embellish themselves and their environment. In China, domestic featherwork production of household products and fashion accessories was practiced as early as the fifth century. Brilliant blue kingfisher, luminous white wild swan, five-colour parrot, long, flexible crane, and varied brown and red pheasant feathers were assembled to create bedcovers, wall hangings, fans, cloaks, jackets, and hats.3 By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, China and Japan exported bird feathers to European consumers who incorporated them into fashion accessories.

In India, domestic peacock feathers were of divine importance and aesthetic value. Though many feathered works do not survive due to their fragility, they were often used as fans and incorporated into headpieces and musical instruments like the taūs (mayuri; Sanskrit: peacock)—a bowed string lute from North India. This collaged court instrument, popular in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, has a lacquered peacock-shaped body with real peacock feathers added to the tail.

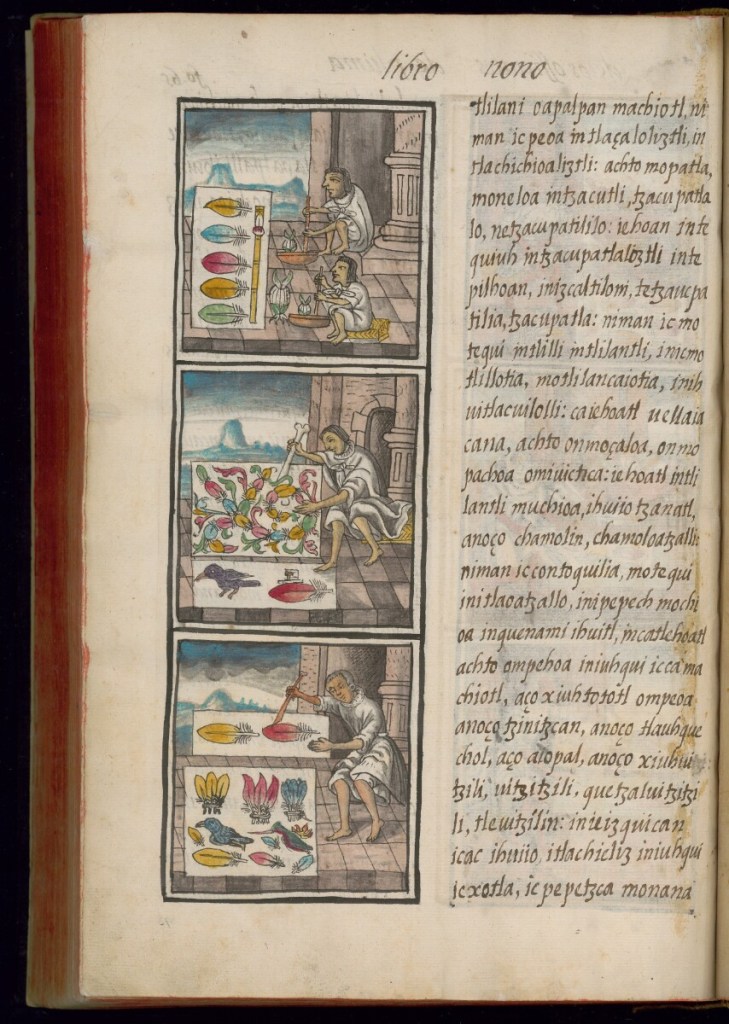

In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, feather workers (amantecas) made featherworks for ceremonial and ornamental purposes.4 A famous manuscript documenting amanteca practices is the Florentine Codex (1577)—so-called after it entered the Medici family’s library in Florence. Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún (1499/1500-1590), Nahua elders, authors, and artists created the encyclopedic Codex in Tlatelolco (today Mexico City). The Codex contains parallel columns of Nahuatl and Spanish texts and more than 2,500 hand-painted images, with illustrations and commentary on Nahua amantecas explaining the difference between ‘true’ and ‘fraudulent’ feather workers and how to ornament feather works to sell them quickly.5 By the sixteenth century, amantecas in New Spain (today Mexico) exported luxury featherworks like ‘feather mosaics,’ shields, mitres and infulae to Europe and Asia.

Mesoamerican feather work also influenced European interest in the natural world. The famous Feather Book, created by Dionisio Minaggio, the Chief Gardener of Milan, and numerous undocumented assistants in 1618, contains approximately 300 feather pictures of birds and figures like hunters, actors, musicians, and dentists. The feathers are primarily from local birds and a few foreign ones (e.g., the kingfisher and parrot) imported through a circulatory court economy. Though the exact reason Minaggio crafted this downy book is unknown, it was likely in response to the wave of imported luxury feather mosaics made by Indigenous amantecas in Central and South America.

Trading in ‘Fancy Feathers’

Europeans’ growing control over lands and seas and desire for feathered art and fashions resulted in their monopoly over the global feather trade in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A “sartorial French invasion” undermined the Canadian fur trade, supplanting beaver fur imports with fashionable foreign Manchurian crane, kingfisher, parrot plumes, and local chicken and cockerel feathers dyed brilliant hues.6 By this time, major European cities were trading domestic feathers from larks and swallows and foreign plumes from Egyptian herons, North African ostriches, and Indonesian birds of paradise.7

Throughout the early modern period, plumes were conveyed along the Asian trade route through the Mughal, Safavid, and Ottoman courts into Europe. Muslim agents carried African feathers (famously, ostrich skins) via camel caravans from interior regions of Africa across trans-Saharan routes to North and West Africa, where Jewish mercantile families oversaw feather exports to European ports in Livorno, Marseilles, Paris, and London.8 As maritime trade routes in the Atlantic expanded, birds and their feathers often travelled via the Triangular Trade Route, with feather stocks carried between Britain, the West Coast of Africa, the West Indies, and North and South America.9 Once unloaded from ships, feathers or skins with unplucked plumes were passed onto feather manufacturers’ specializing in feather products, from mattresses and hair pieces to artificial flowers and the sale of individual ‘fancy feathers.’

Nature Printing

Using animals for artistic impressions often requires the sacrificial death of the specimen, be it a bird, butterfly, or fish. This materialized in various types of nature printing in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Forbes’ birds are depicted approximately to size in a technique similar to that described by the naturalist and ornithologist George Edwards’ (British, 1694-1773) “Receipt for making Pictures of Birds, with their natural Feathers” in A Natural History of Birds (1747). To create a feather collage, the artist prepared the board by applying a layer of white paper to the surface and letting it dry; then, the artist drew the bird’s contour according to its natural size and added the background elements. Next, the bird’s bill and legs are added in watercolours. Empty space is left within the drawn outline of the bird in preparation for it to be feathered. Layers of gum Arabic are applied until the paper surface reaches the thickness of a shilling to feather the paper bird.

When your piece is thus prepared, take the feathers off from your bird, as you use them, beginning always at the tail, and points of the wing, and working upwards to the head; observing to cover that part of your draught with the feather, that you take from the fame part in your bird, letting them fall one over another in their natural order.10

Steel pliers and a pencil (brush) are helpful when applying individual feathers. With a feather held fast between a small set of pliers or tweezers in one hand, the artist dipped a large brush in water to moisten the gummed groundwork using the other hand. Next, the artist adhered the feather to the moistened gum surface, secured by leaden weights until dry. This process was continued until the entire paper bird was feathered. The final step was to smooth and trim any rebellious feathers into place and cut out a circular piece of paper for the eyes to be watercoloured.

European techniques differ from Indigenous Mesoamerican feather techniques. For example, Mexica amantecas affixed feathers to thin paper supports and then applied each feather applique to the primary paper backing until the composite ‘feather painting’ was completed. Another method required an agave cord to hold the feathers in place while assembling three-dimensional objects like fans and headdresses.11

If printing with butterfly wings, one practiced ‘lepidochromy,’ “a most interesting description of a very elegant form of decorative art, which may be termed the decalcomania of butterflies’ wing” on paper, porcelain, or glass.12 George Edwards also includes a “Receipt for taking the Figures of Butterflies on thin gummed paper” in a 1748 French edition of his Natural History of Diverse Birds—a recipe and practice he claims to have introduced to England for the first time.13 However, an anonymous second edition of The art of drawing, and painting in water-colours (London, 1732) offers similar instructions on making “Impressions of any Butterfly in a Minute in all their Colours” at an earlier date.

This ecological artistic technique was by no means local to Europe. The author of a lepidochromy manuscript containing 172 drawings of butterflies remains unknown. However, it is highly likely that Friar José Mariano da Conceição Veloso (Brazilian, 1742-1811), a Franciscan priest and botanic researcher particularly interested in butterflies, commissioned the book.14 The hidden hands who captured and killed the butterflies and prepared them for lepidochromy by pressing them between two sheets of paper and adding watercolour and traces of gold pigment remain unknown.

Nature printing with dried fish specimens was widespread in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Dutch naturalist Johan Frederik Gronovius (1690-1762) ‘invented’ this technique, which involved removing the skin from one side of the animal and affixing it to a paper or cardboard sheet. Gronovius’ “method for preparing specimens of fish, by drying their skins” was read during a meeting of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London on 4 March 1741 and published shortly after in 1742. Friar José Mariano da Conceição Veloso, who commissioned the lepidochromy manuscript mentioned above, also commissioned a “fish herbaria” consisting of 85 dried fish specimens. Other naturalists like Laurens Theodorus Gronovius (Dutch, 1730-1777), William Yarrel (British, 1784-1856), Philibert Commerson (French, 1727-1773), William Dandridge Peck (American, 1763-1822), Domenico Agostino Vandelli (Italian, 1735-1816), and José António de Sá (Portuguese, ?-1819) also made fish prints from nature, though within a much more scientific framework aimed for lasting study as museum specimens.15

Patrick Russell (Scottish, 1726-1805), the herpetologist who published An Account of Indian Serpents (1796)–the same publication Forbes cut plates from for many of his collages–also did something similar but with snakes. He removed the skulls and organs of dried snakes and glued the skins to herbarium sheets. The British Museum acquired Russell’s (this attribution is questionable) specimens in 1837 (71 specimens bound in a single volume) and 1904 (97 specimens on individual sheets). Russell’s dried snake skin collection appears independently of his designs published in An Account of Indian Serpents, which were based on drawings made by Indian artists.16

Ornamental Feather Art

On 26 April 1748, Samuel Dixon (Irish, d. 1769), an established painter and picture dealer in Dublin, advertised a “new invention”—a series of flower pictures “not only ornamental to Lady’s Chambers but useful to paint and draw after.”17 Forbes’s featherworks respond to an eighteenth-century European artistic practice that was both decorative and functional and widely embraced by women and men of the upper and middle class with an interest in ‘polite science.’18

Artists no longer needed to be artists-naturalists to make ornithologically accurate feather artworks. Two years after Dixon’s flower pictures, he created a set of bird feather paintings using prints from George Edwards’ Natural History of Uncommon Birds (4 vols., 1743-51). The 1750 series of “curious foreign bird pieces” made in basso-relievo (embossed paper-mâché) and feathers included twelve ‘paintings,’ among them The Brown Indian Dove and The Lesser Mock-Bird and the Black and Yellow Manakin.19

Other featherwork examples include the bird painter Peter Paillou’s (British, c. 1720-c.1790) feather picture of ‘A Horned Owl from Peru’ presented at the Free Society of Artists (1761–83) in 1778; a Military Macaw (Psittacus militaris) executed in the feathers and preserved on paper by one of the jurist and naturalist’s Taylor White’s daughters, Anne or Frances around 1787 after the manner recommended by Edwards in his History of Birds; and White’s second wife, Frances (Fanny) Armstrong’s (British, 1720-63) golden pheasant made with feathers and a painted bill and legs.20 C. Fasmann’s (German, late 18th-early 19th century) male Eurasian Bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) and Bohemian Waxwing (Bombycilla garrulus) made of bird feathers and watercolours on board fit squarely within the fashion for nature printing as a form of collage. It is this broad social interest in ornamental nature which Forbes experiments with decorative, vibrant feathers he viewed at Anjengo and Ahmedabad.

References

1 Patrick Elliott, ed., Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2019), 26; Peter Blake, Dawn Ades, and Natalie Rudd, Peter Blake: About Collage (London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 2000), 37.

2 Kristopher W. Kersey, “In Defiance of Collage: Assembling Modernity, ca. 1112 ce,” Archives of Asian Art 68, no. 1 (April 2018): 1-32.

3 For early and medieval Chinese featherwork, see Olivia Milburn, “Featherwork in Early and Medieval China,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 140, no. 3 (2020): 549-564.

4 For Pre-Columbian Peruvian featherwork, see Heidi King, ed., Peruvian Featherworks: Art of the Precolumbian Era (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012).

5 The Mexica Codex Mendoza (c. 1541) is a earlier Mesoamerican codice that comments on and depicts feather workers and their craft.

6 On the competition and eventual monopoly of feathers over furs, see Elisabeth Gernerd, “‘Feather Muffs of all Colours’: Fashion, Patriotism, and the Natural World in Eighteenth-century Britain,” Apparence(s) no. 11 (2022).

7 For more on European featherwork between 1500-1800, see Stefan Hanß, “Making Featherwork in Early Modern Europe,” Materialized Identities in Early Modern Culture, 1450–1750: Objects, Affects, Effects, eds. Susanna Burghartz, Lucas Burkart, Christine Göttler, Ulinka Rublack (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021), 137-185.

8 Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Plumes: Ostrich Feathers, Jews, and a Lost World of Global Commerce (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 85.

9 Elisabeth Gernerd, “Fancy Feathers: The Feather Trade in Britain and the Atlantic World,” In Material Literacy in Eighteenth-Century Britain: A Nation of Makers, ed. Serena Dyer and Chloe Wigston Smith (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020), 199-201.

10 George Edwards, “Receipt for making Pictures of Birds, with their natural Feathers,” in Essays Upon Natural History and Other Miscellaneous Subjects (1770), 117-9.

11 Alessandra Russo, Gerhard Wolf, and Diana Fane, eds. Images Take Flight: Feather Art in Mexico and Europe (1400-1700) (Munich: Hirmer, 2015), 23

12 Scientific American Vol. LX, May 11, 1889, 288.

13 This recipe appears again in his Essays Upon Natural History and Other Miscellaneous Subjects (London, 1770).

14 “Uma [colecção] de borboletas impressas pela fécula colorante de que se cobrem as membranas das suas asas, obra tão rara e estimável que tem o suplicante notícia não haver outra em algum dos Gabinetes reais da Europa”; “A [collection] of butterflies printed by the colouring starch with which the membranes of their wings are covered, a work so rare and estimable that the supplicant is informed that there is no other in any of the Royal Cabinets of Europe.” AHU, Reino, 2719, from David Felismino, Saberes, natureza e poder: coleções científicas da antiga Casa Real Portuguesa (Casal de Cambra: Caleidoscópio, 2014), 35. Author’s translation.

15 Luis M. P. Ceríaco et al., “The Fish Collection of José Mariano da Conceição Veloso (1742–1811) and the Beginning of Ichthyological Research in Brazil, with a Taxonomic Description of the Extant Specimens,” Zootaxa vol. 5391 no. 1 (2023): 6-7.

16 Patrick D. Campbell, “The Acquisition of Dr. Patrick Russell’s Snakeskin Collections,” Hamadryad 37, no. 1&2 (2015): 67-8. See also, Aaron M. Bauer, Gernot Vogel, and Patrick D. Campbell, “A Preliminary Consideration of the Dry Snake Skin Specimens of Patrick Russell,” Hamadryad 37, no. 1 & 2 (2015): 73-84.

17 Ada K. Longfield, “Samuel Dixon’s Embossed Pictures,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 96, no. 2 (1966): 133.

18 Beth Fowkes Tobin, “Bluestockings and the Cultures of Natural History,” In Bluestockings Now!: The Evolution of a Social Role, ed. Deborah Heller (London: Routledge, 2016), 57-59.

19 Faulkner’s Dublin Journal, 4 Apr. 1749.

20 “1037 Psittacus militaris,” in Catalogue of the Leverian Museum, Part I, NB 9th day’s sale, Wednesday 13 May 1806, p. 44, https://archive.org/details/catalogueoflever00leve/page/44/mode/2up?view=theater.

Hidden Hands in the James Forbes Archive

Written by Dr. Anna Winterbottom

View Essay

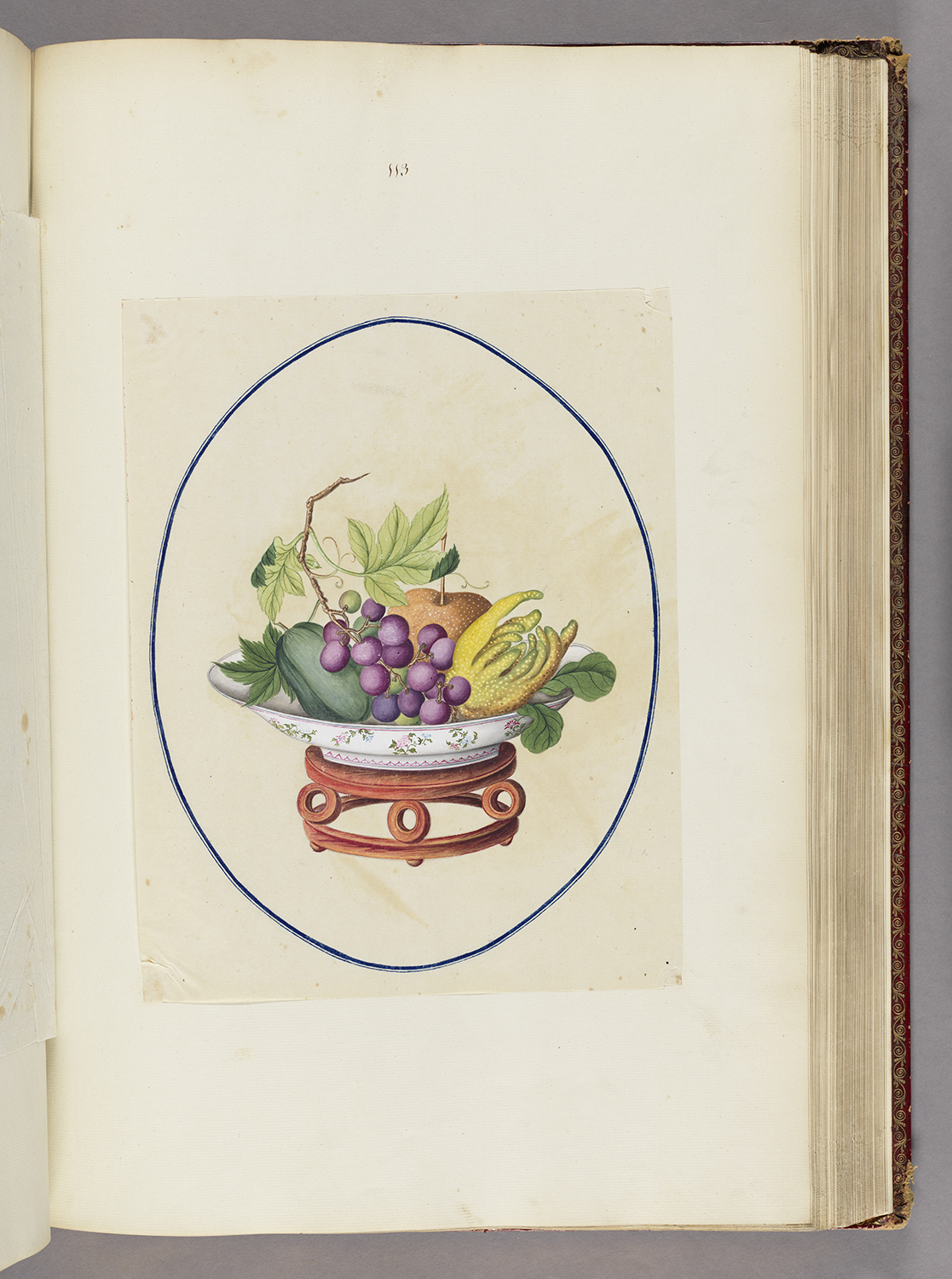

My friends in India were happy to enlarge my collection; the sportsman suspended his career after royal game to procure me a curiosity; the Hindu often brought a bird or an insect for delineation, knowing it would regain its liberty; and the brahmin supplied specimens of fruit and flowers from his sacred enclosures.1

In this preface to his Oriental Memoirs, first published in 1813, James Forbes (1749-1819) acknowledges the help he received in making his natural history collections while in India. Nonetheless, he does not name the co-creators of his archive: recognising only their group identities. In this case study, I will discuss some of the likely “hidden hands”, who were involved in hunting, collecting, depicting, and describing natural historical specimens.

1. Servants, enslaved people, attendants, and advisors

Forbes began his career in 1764 as a “writer”, the lowest rank of the East India Company’s (EIC) bureaucracy.2 By 1780, he had attained the rank of collector of revenues in Dabhoi (in modern Gujarat). The role gave him control over eighty-four villages and he referred to himself as the “first man in the city”.3 As Forbes moved up the ranks of the EIC, he would have acquired more domestic and official servants.4 By the time he reached the position of collector, Forbes was also in charge of a small bureaucratic establishment. Forbes usually mentions his servants, attendants, and advisors only in passing, but these references reveal that these men (and perhaps some women and children) would have been important to his ability to make his drawings and collections while in India.

In 1768, in a letter describing his encounter with a “Cobra de Capello” (Naga naga), Forbes refers to his “upper servant”, whom he calls Mahomet. Mahomet seems to have been involved in enabling Forbes to see the snake and (if Forbes’ account is to be believed), to draw it from life. He also reported later to Forbes that the snake handler, who had exhibited the snake for Forbes, had later shown it in the market, where it bit and killed a young woman. Forbes tells us that Mahomet was a devout Muslim and that he “set me down in his Kalendar as a lucky man”, implying that Mahomet was a literate man.5 Forbes’ reliance on the snake handler to enable him to view the dangerous cobra up close was typical for British naturalists of this period.6

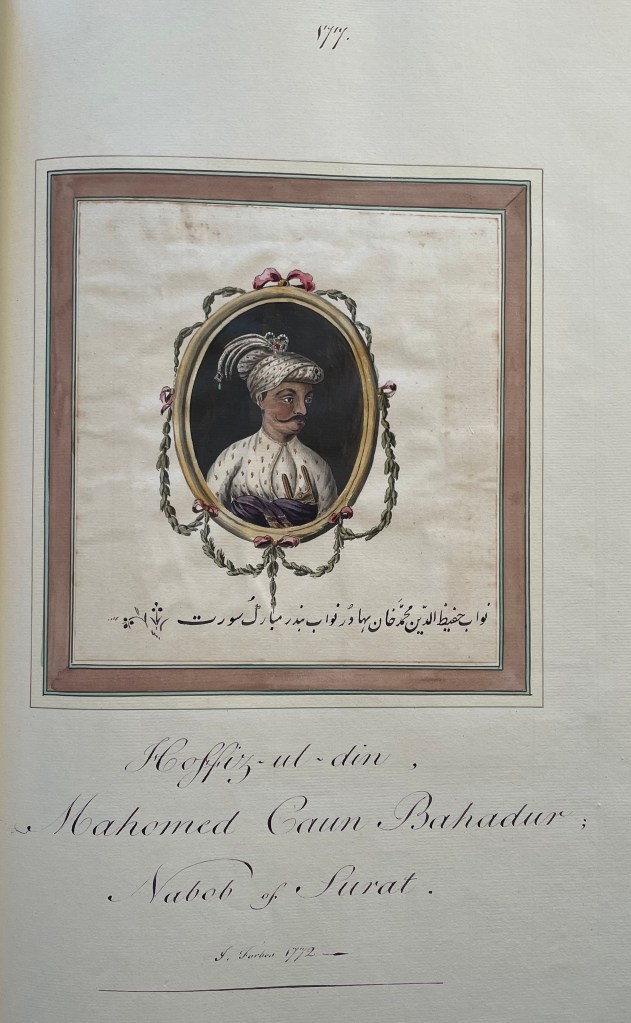

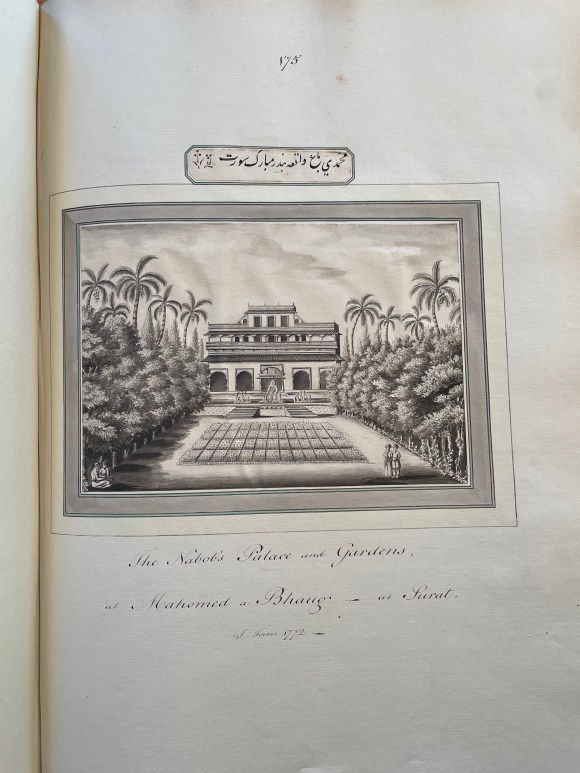

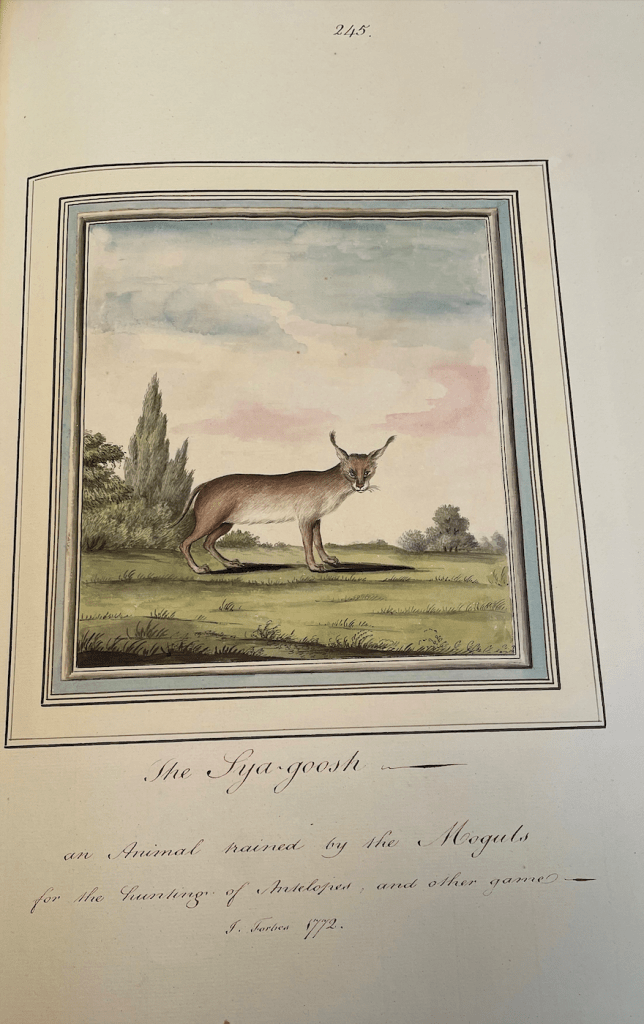

In 1771, Forbes embarked on a trip to “the hot springs at Dazagon” (likely Dasgaon in Raigad District).7 This trip, which Forbes describes as for his health, also seems to have had some diplomatic aims, as Forbes describes meeting with rulers including Raghoji Angria (1759-93), ruler of Alibag8 and Mir Hafizuddin (1763–90). Forbes’ drawings of Mir Hafizuddin and of his gardens also have accompanying text in Persian.9 As Forbes himself makes no reference to learning Persian, this suggests that by this time, Forbes had an interpreter (or dubash) to aid him in his work (unless Mahomet, mentioned above, also served in that capacity). His interpreter likely also helped Forbes name some of the animals he encountered while hunting in the retinue of Mir Hafizuddin. For example, when describing a caracal he saw used in the hunt, he gives the Persian name, “syah-gosh” (siya gosh) meaning “black ear”, and notes correctly that the Mughals had introduced it to several parts of India.10

Forbes expressed disapproval of slavery in the Atlantic context and in the Dutch East Indies, but like many of his British contemporaries, he regarded it as less harsh in India and at the Cape of Good Hope.11 He refers twice to purchasing or owning enslaved people. The first reference is from his time in Anjengo (Anchuthengu, Kerala), where he was appointed as a factor in 1772. Here, he describes how a failure of the rains could lead people to sell themselves or their families into servitude. He goes on to describe buying two children, aged eight and nine, whom he sent to an unnamed female friend in Bombay. He excuses himself by arguing that they were well treated and would otherwise have been sold into “miserable bondage with some native Portugueze Christian”.12 The second reference, which occurs only in passing, is to “a little slave boy” who was part of his household in Bharuch and whom he later brought with him to England.13 Exactly what role these enslaved children would have played in Forbes’ collecting activities is not described, but it is easy to imagine them performing activities like collecting seeds, which require small and nimble fingers. For example, Forbes referred to collecting 200 seeds from the gardens of the Nawab of Surat during a second visit in 1783 when he was about to embark on his return journey to England.14 The enslaved boy who accompanied Forbes to England would have accompanied him at this time and could have performed this task.

From the time Forbes was promoted to a seat on the Anjengo council, he established his own household. This meant that he had servants dedicated to maintaining the house and gardens, as well as his personal attendants and interpreter(s). One of the most important for Forbes’ natural-historical work was his gardener, whom he refers to as Harrabhy (Harabhai). Forbes describes Harabhai as presenting him daily with “nosegays of mogrees, roses, and myrtles” as well as vegetables.15 This practice, of presenting a daily offering from the garden, was widespread in India at the time. The basket or tray with the offerings was known in Hindi as ḍālī and became “dolly” among the “Anglo-Indian” jargon spoken by Europeans. Similarly, mālī, the Hindi word for both gardener and garland-maker, was corrupted to “molly”, so that references to “the molly with his dolly” were apparently common by the 1750s.16 The East India Vade-Mecum, a guidebook for Englishmen in the Company’s service, describes the status and role of a mālī in some detail. It begins by noting that his dress and wages are “scarcely better than that of a common laborer”, but continues to note the skills of these men:

It would surprize an European to see with what precision maullies sow and cover their seeds; the seasons for which they are perfectly acquainted with, even though the greater portion of the horticultural produce in that quarter consists of exotics: this is the more remarkable, because there is no book of gardening extant in the Hindui language; and if there were, the chances would be, at least a thousand to one, that the maully could not read it.17

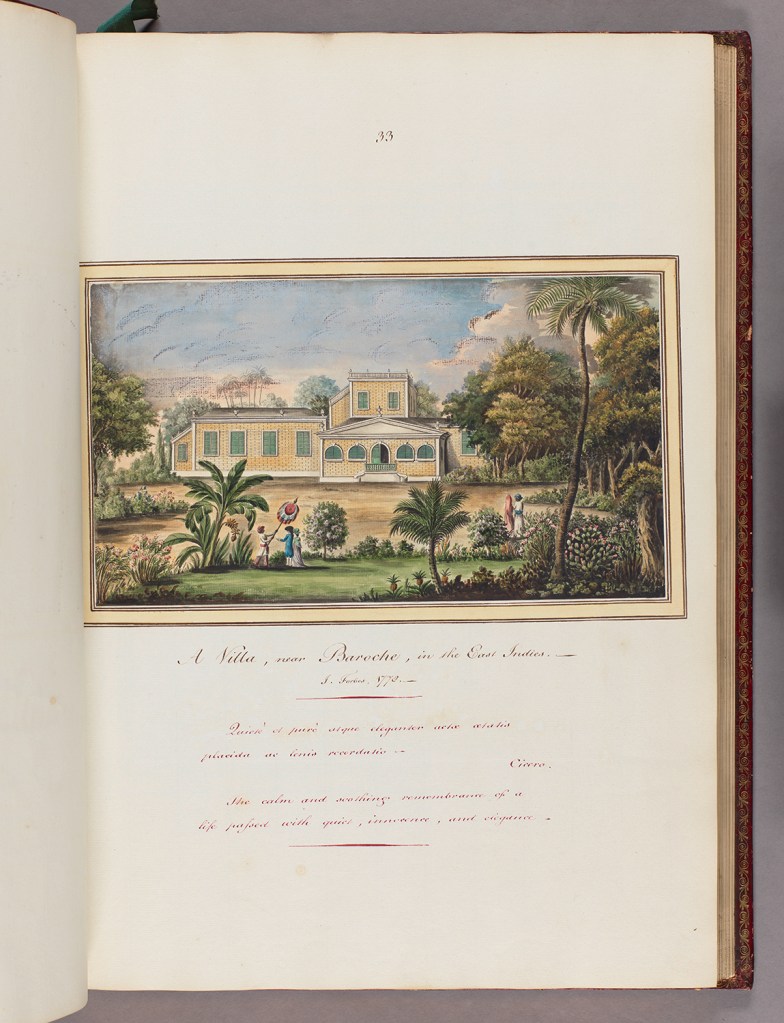

The handbook goes on to describe the irrigation systems used for gardens, fed by well water. In the Oriental Memoirs, Forbes describes his own six-acre garden in Bharuch (Figure 5) as being modelled on an English garden but sown with plants from different parts of India and China.18 He describes the system of irrigation used by the gardeners to maintain the flow of water to all parts of the garden, involving raising the water from a well by a yoke of oxen and directing it through artificial channels.19 This system was clearly implemented and managed by Harabhai. Harabhai also seems to have managed the animals kept in the gardens. James Forbes recieved a letter from his sister, Elizabeth Dalton,in 1780 when she was in Baruch and James in Dabhoi, noting that while he had sent his sister an antelope, Harabhai had “thought [the animal] no friend to some of your favourite plants” and that the antelope had therefore been given away.20

Forbes may have been indebted to Harabhai not only for many of the plants which he drew, but also for information about snakes. He wrote to his sister in 1778, “[Snakes] the head gardener will on no account destroy, calling them Genii of the garden: he often speaks to them, accosting them under the endearing appellation of father and mother.”21 Several of the more realistic drawings of snakes made by Forbes seem to originate in the gardens of Bharuch. Forbes also noted some Indian stories about snakes; relating for example that the mongoose eats snakeroot (Rauwolfia serpentia) to cure snakebite. This story is not based on the mongoose’s actual behaviour but does signal the role of the plant in treating snakebite. Forbes refers to having been informed of this while in Anjengo, “by many eye-witnesses of the fact”.22 Despite Forbes’ evident respect for Harabhai’s horticultural knowledge, he eventually dismissed him after the gardener was accused of theft. Forbes describes participating in an ordeal in which Harabhai’s guilt was revealed and the subsequent find by his “slave boy” (referred to above) of the stolen goods buried in the garden.23 Forbes apparently did not draw a portrait of Harabhai himself, but an image of a gardener made in 1769 does appear among his drawings now at Yale (Figure 6).24

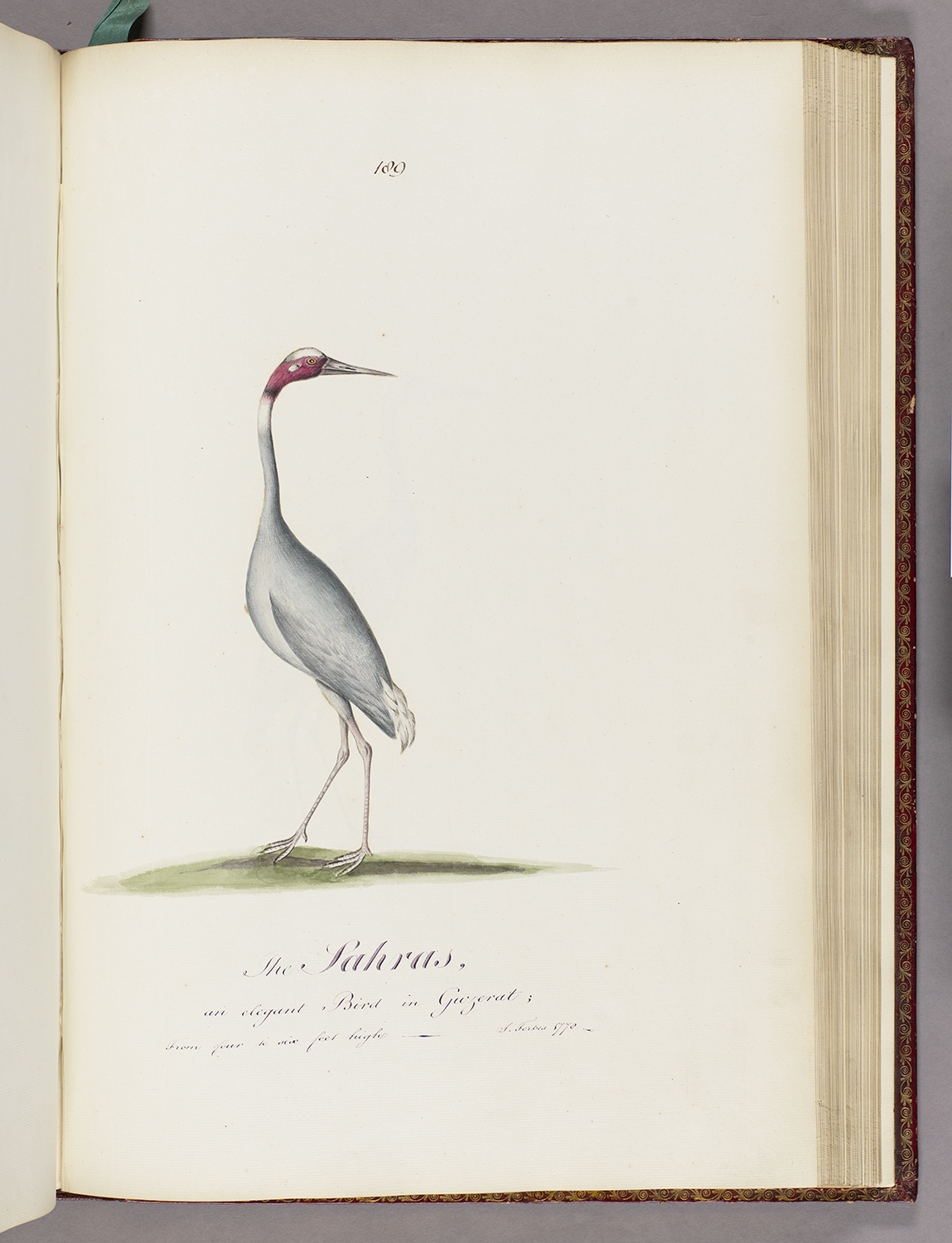

Forbes describes going out on painting excursions accompanied only by a peon, or footman.25 In his landscape views, he sometimes includes a miniature self-portrait in the corner of the image, showing himself sketching the landscape, shaded by an umbrella that the peon is holding.26 The men who served as Forbes’ peons aided with his collections as well. In one passage, Forbes refers to sending his peon to catch a young Sarus Crane, which subsequently became domesticated and moved with Forbes to Bharuch.27 Catching a large bird like the Sarus Crane, which in adulthood is as tall as a human being, is no easy task. Forbes’ servants would also have also been involved in maintaining the large bird in captivity, presumably in his gardens, until he passed the bird on to a friend who was returning to England.28

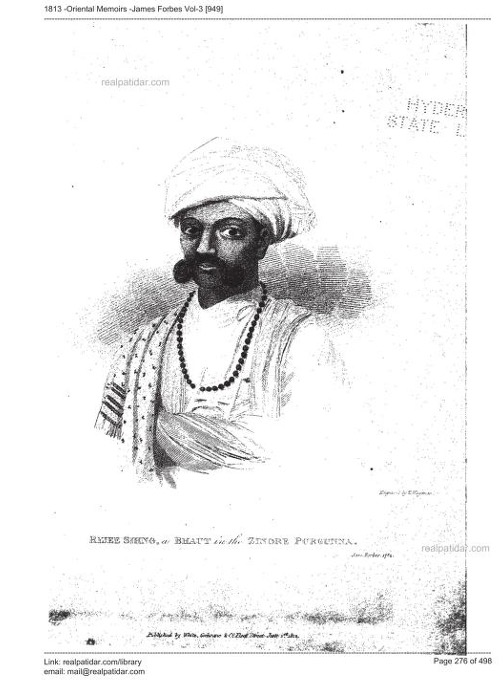

By the time Forbes had become the Collector of Dabhoi, he was involved in complex negotiation with several local and regional powers. To do so, he would have had several advisors in addition to translators. Forbes describes and includes a portrait of one of these men, “Ryjee Sihng” (Raji Singh), “principal bhaut” (bhāt). Forbes described him as coming from ”a respectable family in the Zinore purgunna, particularly celebrated as a historic bard, or ministrel.” Forbes relied on Raji Singh in his negotiations with the “Gracias” (Garasia a title used by the Koli chieftans of jagirdars or petty states) in Dabhoi. Forbes described Raji Singh as an oral historian, well acquainted with the “character of princes and historical traditions”.

Forbes’ account contains many passages discussing local history and politics. Since he does not appear to have been skilled in Indian languages, many of these details were likely related orally to him by men like Raji Singh. Alexander Kinloch Forbes,29 a later EIC employee, acknowledged the help of a bard in preparing his own account of local Gujarati history, published in 1856.30

2. Friends and patrons

Beyond his own household, Forbes formed friendships and alliances with Europeans and Indians, some of whom acted as patrons or passed on information and materials that he incorporated into his work.

While Forbes was serving as a chaplain and secretary to Thomas Keating from 1775, he was sent with British armed forces in support of Raghunath Rao’s attempts to regain his position as Maratha Peshwa.31 In the Maratha camp, Forbes came into contact with Charles Warre Malet (1752-1815), the English resident at Cambay (Khambhat in Gujarat). Material that Forbes received from Malet is inserted into the Oriental Memoirs, including an image of the Maratha Peshwa32 and a description of the organisation of a Maratha camp.33 In the final volume of Oriental Memoirs, Forbes also devotes a long section to materials sent to him by Malet describing his journey to Calcutta via Agra and Delhi, including an audience with the Emperor Shah Alam.34 Malet, who later became the EIC’s resident at the Maratha court in Pune, was also important in introducing Forbes to artistic circles, including James Wales and his daughter Susanna Wales, and Thomas and William Daniels whose images are also included in Forbes’ archives at Yale and form the basis for some of the images in the Oriental Memoirs.35

Another artist and scholar in Malet’s circles was Sadānand Vyās, whom Samira Sheikh identifies as the author of a series of drawings in Forbes’ archives at Yale showing religious mendicants, Hindus of different castes, and soldiers. As Holly Shaffer notes, “Sadānand’s drawings served as a visual dictionary for at least two Company officials to identify Indian groups or persons perceived as informants, threats or combatants.”36 Sheikh notes37 that Sadānand was also the author of a very detailed map of Gujarat, which was bound into the journal of Anton Pantaleon Hove.38 Susan Gole relates that this map was seen by James Rennell, who commented that “this genuine Hindoo map, contains much new matter… it is remarkable, that it gives the form of Guzerat with more accuracy than the European maps could boast of”. Rennell notes that he acquired his copy of the map from Charles Malet, at whose suggestion it was drawn.39 Forbes does not name Sadānand Vyās, but he describes becoming acquainted in Cambay with a brahmin who was close friends with Charles Malet, who understood English and had read many English books, particularly “a voluminous dictionary of arts and sciences, from whence he had acquired a fund of useful knowledge and a liberality of sentiment uncommon in his caste”.40 Forbes continues to note that “He was fond of drawing and had acquired a skill and judgment in that amusement beyond any other native I ever met; he presented me, upon further acquaintance, with fifty portraits of persons well known at Cambay and the adjacent country, high and low, of different tribes and religious, in their various costumes and distinct character of countenance, together with drawings taken from the life of the most celebrated yogees, sen”.41

3. Family members

Several of Forbes’ female relations seem to have played a part in his natural-historical activities. James Forbes’ original letters from India were addressed to his older sister Mary Ann Forbes (1747-77). He writes that her own interest in natural history, especially birds, had inspired him.42 Mary Ann Forbes later married John Fothergill, then an ironmonger and later a maker of ivory brushes and combs, who was the nephew of the better-known physician of the same name. James Forbes seems to have made use of this connection to establish himself among the community of natural historians in Britain, referring on one occasion to sending a collection of seeds from his garden in Bharuch to Dr. Fothergill.43 Another of James Forbes’ sisters, Elizabeth Dalton (née Forbes; 1753- 1812) accompanied him when he returned to India in 1778, marrying his close friend John Dalton. Elizabeth Dalton and her husband lived with James Forbes in Bharuch, where she evidently shared her brother’s interest in the garden and kept pet birds.44

Forbes’ collections at Yale were originally made for his daughter, Elizabeth Rosea Forbes (1788-1839) and presented to her on her twelfth birthday. Elizabeth Rosea Forbes travelled with her father in Holland and France between 1803 and 1804. She remained close to him after her marriage in 1809 to Marc René de Montalembert, a French emigre who served in the British army in India and contributed at least one image to Forbes’ work.45 It was Elizabeth Rosea de Montalembert who edited the second edition of her father’s memoires, published in 1834. While she offered only a short introduction to the work, the archival collections at McGill suggest that she or another family member may also have worked on some of the illustrations that were republished in a separate volume. Notably, the watermark on a drawing at McGill entitled “the nest of the bottle sparrow”, places it after 1825, six years after Forbes’ death.46 This image, which was based on Forbes’ own illustration in the first volume of his Oriental Memoirs, was not eventually published in the later edition. Nonetheless, the late date of this image suggests the involvement of either Elizabeth Rosea de Montalembert or her son Charles Forbes de Montalembert, who lived with his grandfather from the age of fifteen months and whom James Forbes referred to as “the child of my adoption”.47 Forbes made a final expanded version of his memoirs for his grandson, which remains in the family today.48

Forbes also had family members in India. Whether he himself had a “bibi”, or Indian partner, is unclear. However, in his will he mentions a “Charles Forbes in India, the natural son of my … brother”.49 Since James Forbes left this nephew a bequest, it seems that they maintained contact. What role this Charles Forbes may have played in James Forbes’ collections or other work is unclear, but his presence in the will serves as a reminder that colonial families often included people of mixed heritage.

References

1 Forbes, Oriental Memoirs, 1813, preface, pp. xi-xiii.

2 BL IOR/J/1/5, f. 365, Committee of Correspondence, 17 October 1764 notes Forbes’ appointment, along with seven other young men.

3 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. II, Ch. 23, p. 297.

4 There are few studies of domestic servants in the context of the East India Company. Exceptions include Nitin Sinha, Nitin Varma, and Pankaj Jha eds, Servants’ Pasts: Sixteenth to Eighteenth Century South Asia, 2 vols. (Telangana, India: Orient BlackSwan, 2019).

5 YCBA, James Forbes letter, Bombay, 1768 November 25, vol. 2, p. 145-161.

6 Rahul Bhaumik, “Picturing the Snakes Western Natural History, Visual Culture, and Local Agency in Late-Eighteenth-Century British India.” Nuncius 38, no. 2 (2023): 251–77. https://doi.org/10.1163/18253911-bja10060.

7 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. 1, Ch. 9. Forbes letter 14, Vol. IV, ff. 7-11 and letter 15, Vol. IV, ff. 35-45, YCBA.

8 Forbes, letter 16, Vol. IV, ff. 77-100 and f. 107, YCBA, for the portrait.

9 Forbes, Vol. IV, f. 175 and f. 177, YCBA

10 Forbes, Vol. IV, f. 227 for the caracal. For more information, see Dharmendra Khandal, Ishan Dhar & Goddilla Viswanatha Reddy, “Historical and current extent of occurrence of the Caracal Caracal caracal (Schreber, 1776) (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) in India.” Journal of Threatened Taxa 14 December 2020 | Vol. 12 | No. 16 | Pages:17173–17193 DOI: 10.11609/jott.6477.12.16.17173-17193.

11 YCBA, Letter 61, vol. 9, ff. 9-51. Cape of Good-Hope, 1776 February 7. Much of this letter is reproduced in Ch. 20 of Oriental Memoirs.

12 Oriental Memoirs, Ch. 13, pp. 392-393. Forbes letter 30, vol. 6, ff. 9-31, YCBA.

13 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. II, Ch. 21, pp. 246-248.

14 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. III, Ch. 35, p. 409.

15 James Forbes, Ricordanza: Memoir of Elizabeth Dalton. London: Printed by Edward Bridgewater, 1813, p. 33.

16 Hobson-Jobson, pp. 575, 322.

17 Thomas Williamson, The East India Vade-Mecum; or, Complete Guide to Gentlemen Intended for the Civil, Military, or Naval Service of the Hon. East India Company. London: Black, Parry, and Kingsbury, 1810.

18 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. II, Ch. 21, p. 241. For the image (Figure 5), Forbes archive, YCBA, Vol. 10, f. 33.

19 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. II, Ch. 21, pp. 246-248.

20 Elizabeth Dalton to James Forbes, 15 March 1780.

21 James Forbes, YCBA, Vol. 10, pp. 9-23, Baroche, 1778, June 1

22 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. II, p. 248.

23 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. II, Ch. 21, pp. 246-248.

24 YCBA, Vol. 3, p. 59, detail from an image titled “Hindoos of the Lower-Casts. J. Forbes 1769”

25 The root of the word “peon” is Portuguese, see Hobson-Jobson, p. 697. Forbes describes walking with his “favourite peon” in his letter to Elizabeth Dalton, dated Dhuboy [Dabhoi], 3 August 1780, printed Forbes, Ricordanza, pp. 49-50,

26 Bridge over the river Biswamintree, near Brodera, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill, CA RBD MSG 276-9.

27 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. II, Ch. 22, pp. 276-278. The “Sahras Crane” is Vol. 10, f. 189 in the YCBA, the engraving based on this image was published in Oriental Memoirs, Vol. 2, p. 288. The McGill copy of the image is cut and pasted from the published version.

28 Ibid.

29 Alexander Kinloch Forbes was descended from a branch of the Scottish Forbes clan of Craigievar..

30 Alexander Kinloch Forbes, Râs Mâlâ: Hindoo Annals of the Province of Goozerat, in Western India (London: Richardson Brothers, 1856, Vol. 1), p. ix. Forbes refers to the bard as Dulputrâm Dâyâ, who was given the title of Kuveshwur, or poet.

31 Forbes’ earliest account of his travels with the Maratha camp is in his British Library journal,

32 Forbes, Oriental Memoirs, Vol. 2, plate 3 “The Mahratta Peshwa and his Ministers at Poonah”, drawn from an original Sketch belonging to Sir Charles Malet, Bart.

33 Forbes, Oriental Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 143-157

34 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. III, Ch. 36, Vol. IV, Ch. 37-39.

35 These relationships are explored in more detail in Holly Shaffer, Grafted Arts: Art Making and Taking in the Struggle for Western India: 1760-1910. London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2022. Materials by the Daniels in the YCBA archive include Oriental Memoirs, Vol. IV, after p. 38, p. 62, and p. 64. An image based on an original by Susanna Malet (nee Wales), “The conclusion of a cheeta hunt at Cambay” is included in the Oriental Memoirs.

36 Shaffer, Grafted Arts, p. 91.

37 Samira Sheikh, “A Gujarati Map and Pilot Book of the Indian Ocean, c.1750.” Imago Mundi: The International Journal for the History of Cartography 61, no. 1 (2009): 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085690802456244, p. 75.

38 British Library Add MS 8956, f. 2.

39 Susan Gole, Indian Maps and Plans: From Earliest Times to the Advent of European Surveys (New Delhi, India: Manohar Publications, 1989).

40 Source

41 Oriental Memories, Vol. III, Ch. 31, p. 201.

42 British Library India Office Records (hereafter BL IOR) Mss Eur F380/2, containing copies of Forbes’ original letters, which are addressed to Mary Ann. Her name was removed in later copies of the letter, including those at Yale and the published version in Oriental Memoirs.

43 Oriental Memoirs, Vol. 4, p. 244.

44 Ricordanza, p. 23, 33.

45 Oriental Memoirs, Ch. 14, images inserted between pp. 428-429. The date 1774 given here must in error, since Marc was born in 1777.

46 CA RBD MSG BW003-5.

47 James Forbes, Last Will and Testament, TNA: PRO, PROB 11/1620, sig. 418. Proved 16 September 1819.

48 M. Oliphant, Memoir of Count de Montalembert: a chapter of recent French history, 2 vols. (1872), p. 4.

49 Forbes, Will.