These essays are meant to bring information about collectors, collections, and hidden hands to light.

Photo Essay

Documenting Dr. Danister Perera’s visit to the Redpath Museum, October 2023

Written by Dr. Anna Winterbottom

View Essay

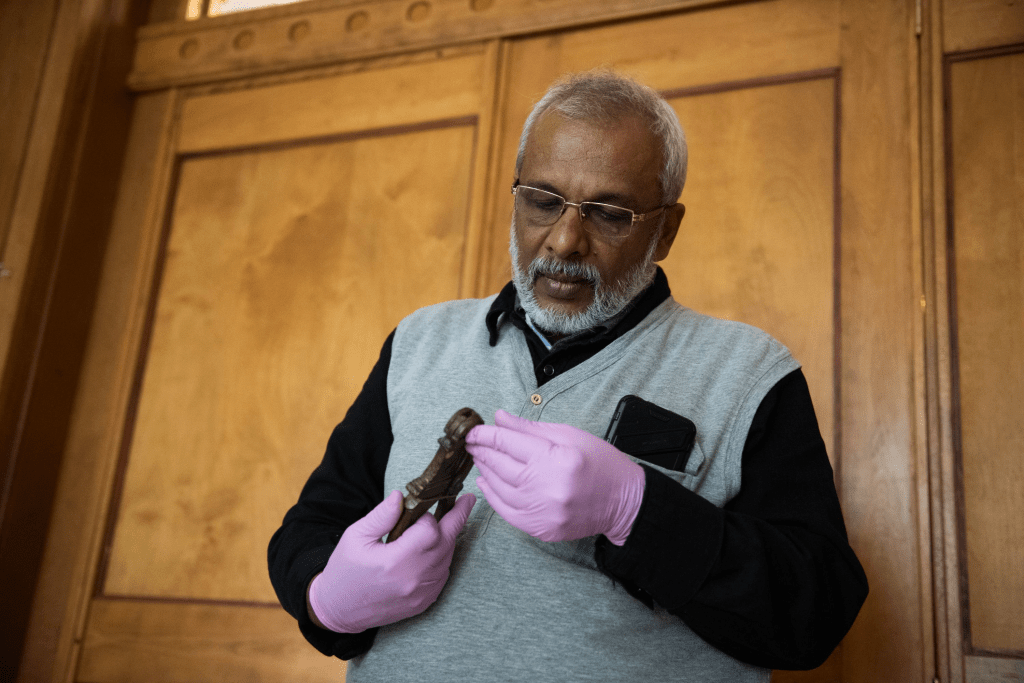

Dr. Danister Perera, visiting scholar associated with the National Library of Sri Lanka, visited McGill during September and October 2023, funded by the Osler library’s Mary Louise Nickerson Travel Grant. He was studying the collection of olas (palm leaf manuscripts) in the Osler library and advising on their digitization and conservation.

During his stay, Dr. Perera visited some cultural belongings from Sri Lanka which are kept in the Redpath Museum. In this picture, he is studying some of the items on display with Annie Lussier, Curator of World Cultures at the Redpath.

The Redpath has many other belongings from Sri Lanka that are not regularly displayed. Most of them were acquired in the 1920s and 1930s by Dr. Casey Wood, a medical doctor and keen collector of items related to the history of medicine and to ornithology. Most of the artefacts relate to traditional medicine in Sri Lanka, which is also called Sinhalese Vedakama (Sinhalese Medicine).

During the visit, we discussed how the cultural belongings should be cared for. Dr. Perera recommended that they should be reorganised according to type. We discussed how protocols for caring for and displaying objects vary according to individual practitioners of traditional medicine in Sri Lanka. Some people might display these belongings as a sign of prestige. Others might keep them with a portrait of their ancestors, but some people would worry that this could led the ancestor to return in search of his or her valuable belongings!

In Sri Lanka, these cultural belongings, like the texts, are believed to have a life of their own. However, even in most museums in Sri Lanka, they are also treated merely as objects. Dr. Perera and his colleagues with an interest in Intangible Cultural Heritage are working to change these ideas. Like manuscripts, the cultural belongings may benefit from human touch and from being used.

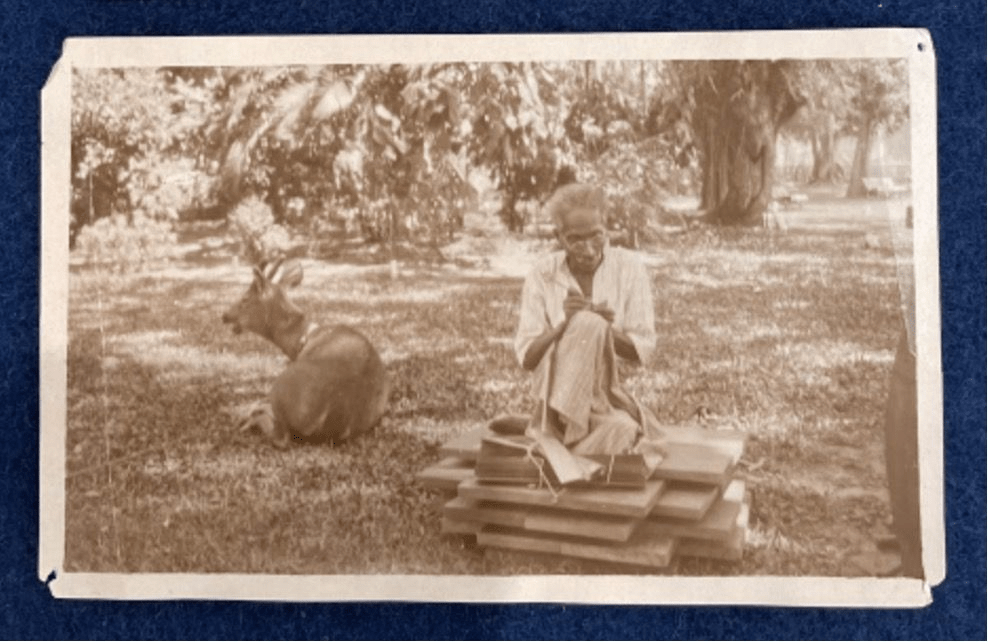

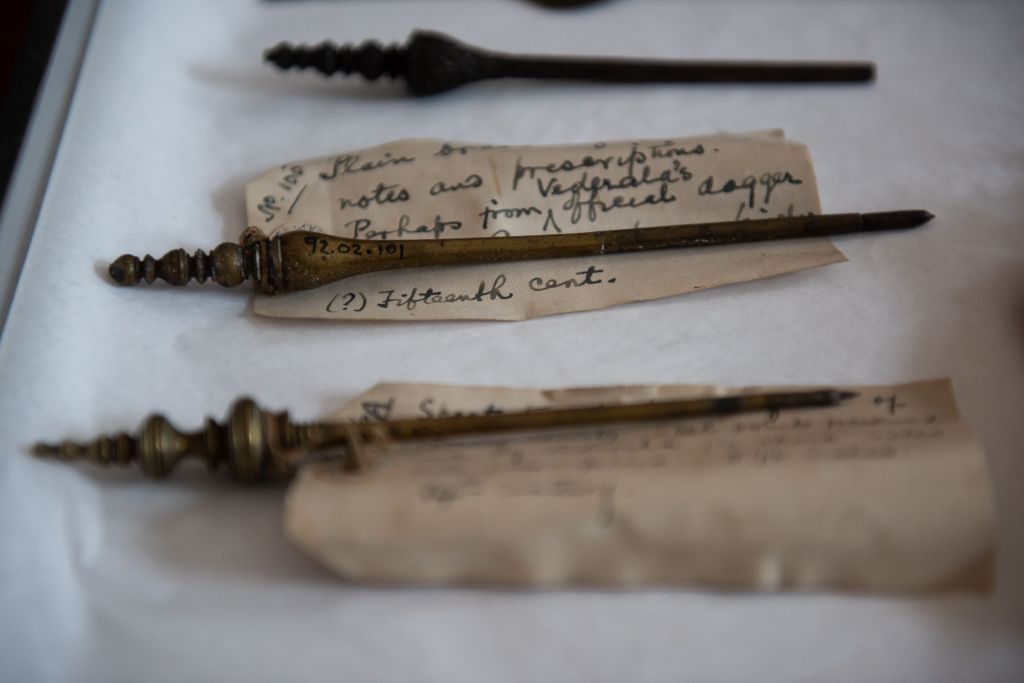

These are styluses. They are used to write on the prepared leaves of the Talipot palm or the Palmyra palm. The art of writing on palm leaves using these styluses had almost died out when Casey Wood visited Sri Lanka in the early twentieth century. Wood took this photograph of a scribe writing on palm leaves.

Dr. Perera demonstrated for us how this was done using one of the styluses from the Redpath Museum.

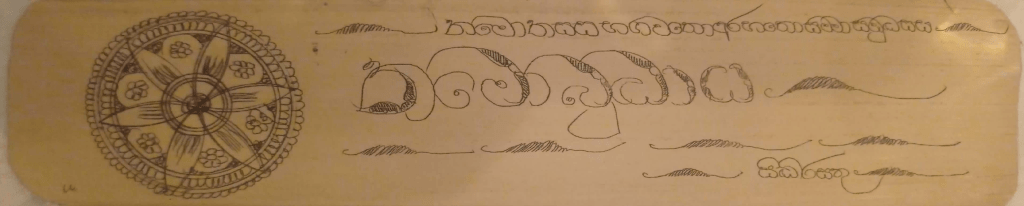

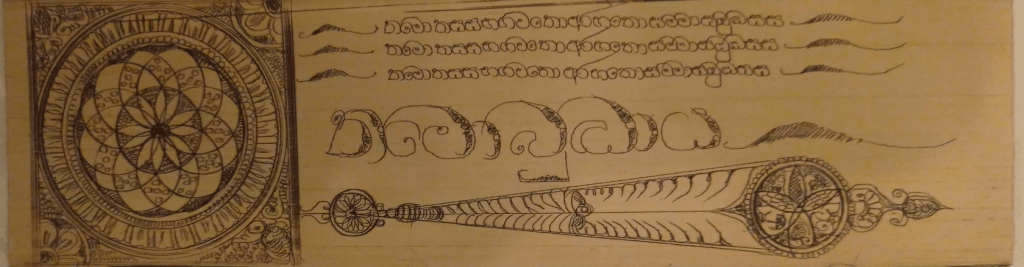

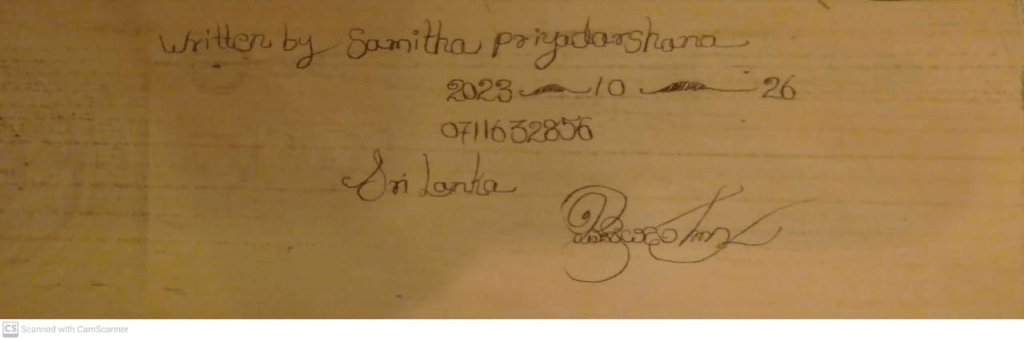

Recently, the art of writing on ola leaves has been revitalised and some young people are now becoming experts. Here is a link to a video showing how the palm leaves are harvested and prepared for writing. Here are some palm leaves inscribed by Mr Samitha Priyadarshana who was trained at Sri Siddhartha Palm Leaf Manuscript Study and Research Institute, Ridigama, Sri Lanka.

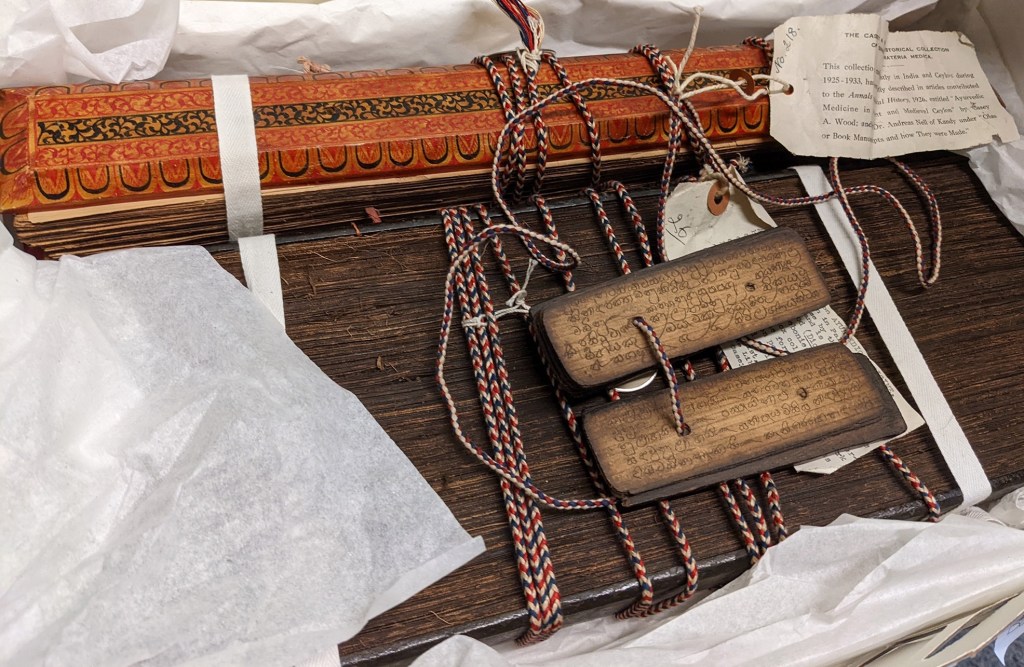

Texts are used to record information, like the many texts dealing with medicine and healing in the library collections. But they also have other roles. The collections include an amulet, meant to contain a text intended to be worn on the body to help in the healing process.

The texts that were worn in these amulets were written on thin sheets of copper and then rolled up to fit inside them. They often contained diagrams and symbols intended to ward off harmful influences from the planets or from demons. The best mantras for the patient might be selected after consulting their horoscope.

The collection also contains other items, like these spectacles, meant for a high-status physician. The frames are made from ivory, a very valuable material in Sri Lanka, where tusker elephants are rare. The lenses are made from rock crystal (quartz, called Diyatharippu in Sinhala).

Only one family in Sri Lanka still makes these spectacles. You can watch a video about their work here.

Another high-status item in the collections is the dagger. Casey Wood reported that these daggers were worn by doctors. Some had an additional opening in the sheath meant to contain a stylus. Other smaller holes in the sheath could contain deadly poisons!

Also in the collection are some small folding knives, meant for cutting and smoothing the ola leaves. There are also some larger knives, which Casey Wood reported were used for cutting down branches to be used as food for elephants. Even these practical knives are quite decorative, suggesting that they may have been used in connection with the Kandyan court.

Also in the collection are some examples of lime cutters. The lime is placed in the blade and held above the patients’ head. The lime is used to extract the disease. Once the disease has been extracted, the limes should be placed in a body of moving water, like a stream or river, to carry it far away.

Casey Wood photographed a lime-cutting ceremony that he witnessed in Anuradhapura, the ancient capital of Sri Lanka.

Held in the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill

For a recording of a modern contemporary lime cutting ceremony, you can watch this video.

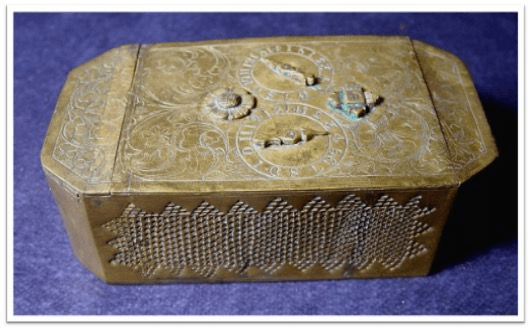

Many of the belongings in the collection are containers meant for carrying pills, pastes, and powders. These are made from materials including ivory, horn, wood, and coconut.

Some of the copper boxes in the collection are quite unusual. These may have been meant to contain small quantities of metallic medicines. In their forms, they are quite similar to Dutch tobacco boxes, but it is difficult to tell which came first. Two unusual boxes use clock-faces as combination locks. These could have been used not only for medicine but also for jewellery or other valuable items.

In this brief photo essay, we have discussed a few of the items in the Redpath Museum and associated collections at McGill. If you have questions, please contact us here. You can also watch Dr. Perera discuss the collections of palm leaf manuscripts at McGill here.

Sri Lankan Medical Manuscripts as Sources for Medical History and the Revitalization of Traditional Knowledge

Written by Dr. Danister Perera

View Essay

The Osler Library contains 21 olas (palm leaf manuscripts) from Sri Lanka on medical subjects written in Sinhala, Sanskrit and Pali. There are a further 100 manuscripts in the Rare Books and Special Collections of the McGill library, many of which deal with medical, astrological, or ritual practices and Buddhist religious texts. These manuscripts date from between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries and were collected in the 1920s and 1930s by Dr Casey Wood. These manuscripts are now in the process of being scanned and catalogued. I visited McGill in September and October 2023 to study these manuscripts, supported by the Mary Louise Nickerson travel grant. I also worked with the project “Hidden hands in Colonial Natural Histories,” funded by SSHRC, which is making possible the scanning and cataloguing of these manuscripts. Before moving on to discuss the manuscripts in the Casey Wood collection, I will introduce Sri Lankan palm leaf manuscripts in general, discussing their significance, how they are made, and other significant manuscript collections in Sri Lanka and beyond. I will also give some background about traditional medicine in Sri Lanka.

Palm leaf manuscripts have a long history in Sri Lanka, India, and several parts of Southeast Asia. They can be considered firstly as cultural property of a documentary heritage. They represent the visible tip of an iceberg, which is made up from skilled practices, oral traditions, and written manuscripts. These manuscripts can be used as historical sources, to inform us about indigenous science, art, and literature. They are a form of intellectual property, both in terms of the information they contain and in their own physical attributes. These attributes include the materials used in their making, their size, covers, the style of letters used in writing on them and the designs and illustrations they contain.

Casey Wood’s collaborator, Andreas Nell, was one of the first to describe in detail the process of making palm leaf manuscripts. Nell, a Dutch Burgher, was a well-known doctor and scholar in Sri Lanka and he was commemorated in 1991 with a stamp in the “national heroes” series. Nell, writing in in 1928, noted that the use of olas was likely to be superseded by printing. However, the art of making these manuscripts was never forgotten and has recently been actively revived by some monastic centres in Sri Lanka, who offer training to young people. Making the manuscripts is a long and laborious process which is imbued with cultural norms and practices. While inscribing the manuscripts is an art, making the manuscripts is a science. Notably, conservation techniques, intended to ward off insect pests, are present from the outset.

Palm leaf manuscripts are made from two species of palm trees, the Talipot (Coryphaumbraccilfera) and the Palmyra (Borassus flabellifer). The process begins with plucking the spathe of the palm leaf, which contains the immature leaves, just as it is about to open. The leaves are then removed as strips, separated, and made into rolls. The time that the leaves are plucked is important, because close to the time of the new moon is the time when the water content of the tree itself is reduced. This is the time chosen to harvest the leaves and it is thought that the lower water content of the leaves at this time will help to guard the final manuscript against attacks by pests. Offerings are made to the tree the day before the leaves are plucked, to ask permission from the tree, which is considered a living being. The plucking itself is accompanied with the recitation of mantras, the blessing of the knife used in cutting the spathes, and traditional drumming. The tree and later the plucked spathes are wrapped in white cloth and taken to the temple in a ritualistic procession as a sign of respect.

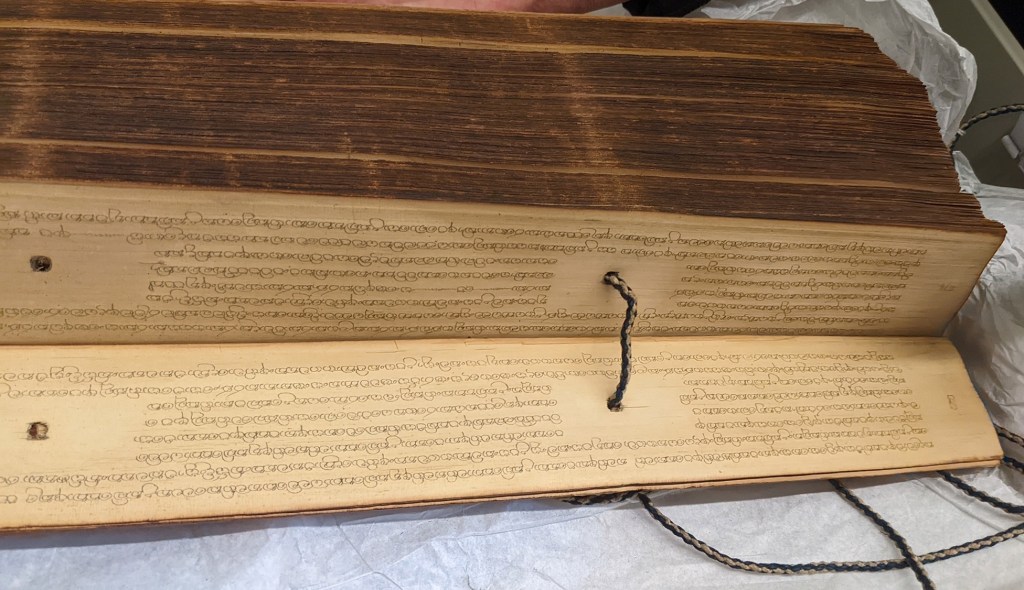

The leaves are boiled with various herbs, which vary according to place but can include the leaves of fruit trees, many of which have anti-microbial and anti-fungal activity. The leaves are hung up to dry in the sunlight for three days and then under moonlight. They are also exposed to the dew, which is thought to give the palm leaf a whiter colour, like the moon itself. After seasoning and polishing, the leaves are cut to different sizes. The width of the leaves used in manuscripts is quite regular, for examples the width of the olas at McGill range from 2-7cm, with most measuring between 3cm and 5cm. The length of the manuscripts shows much more variation, with the length of the McGill manuscripts ranging between 10cm and 60cm. Traditionally, the longest and widest part of the leaves – the central part – is used to make Buddhist manuscripts. The second longest part is for medical manuscripts, the next part is for other arts and literature, the next part is for astrology and the smallest parts are used for mantras (or sometimes for black magic). This reflects the prestige of the different manuscripts and their use: for example, medical handbooks tend to be written on the shorter parts of the leaves so that they can easily be transported, and mantras can be worn on the body in amulets. Holes are punched in the ola leaves mid-way between the longitudinal sides, Nell notes that the position of the holes was determined by folding the ola in three and then in four and making the holes between the two folds.

Inscribing the palm leaf is done by using a metal stylus, which has a sharp end. The letters of the Sinhala alphabet are adapted to the technology of palm leaf manuscripts in their rounded appearance. They are easier to write without splitting the palm leaf than scripts that use straight lines. There is usually no space between words in text in manuscripts, and no punctuation, and task of separating words and phrases should be done by the reader according to his or her knowledge. Sinhala script has four styles of letter (called “elephant”, “swan”, “crow” and “lion”) and the type used is selected according to the subject of the manuscript. Once the manuscript has been inscribed, the next stage is inking the manuscript to make the letters stand out. This is done with an oil, derived from the resin a tree endemic to Sri Lanka (Shorea oblongifolia, also calledDoona zeylanica), mixed with the charcoal of another tree species, Trema Orientalia, also known as the gunpowder tree. The blackening paste in fine form applied on the surface fill the grooves of letter made by inscribing and the letters become visible. The sharp fragrance is a good insect repellent and keeps the folios protected from pest attacks and the chemical composition has effective anti fungal and antimicrobial properties.

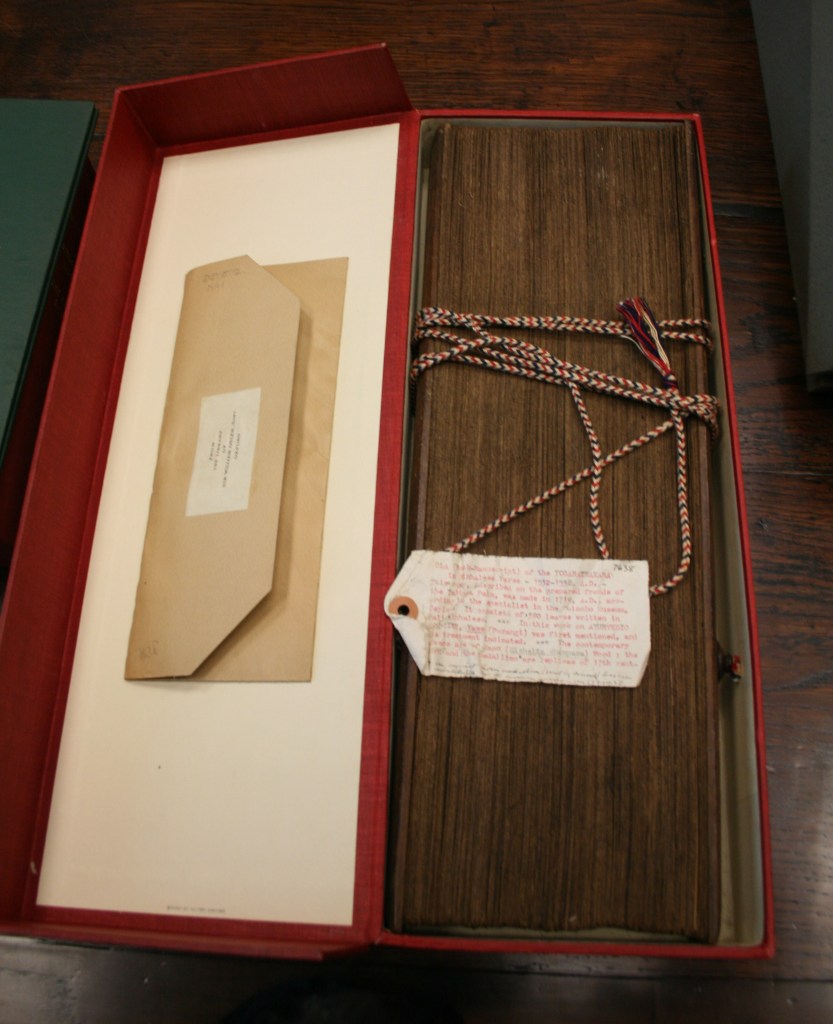

Finally, the manuscript is rubbed with the flour of finger millet, Eleucine coracana, to remove excess oil. Once the written manuscript is complete, a cord made from bowstring hemp, Sansaviera zeylanica, is threaded through the holes in the manuscript. The leaves are then slotted between the boards (kambā), which are usually made from hardwoods and often decorated with lacquer. The type of wood sometimes indicates the status or value of the manuscript. But there are uncommon covers made of metal, silver or rarely gold plated, and carved with traditional arts. The cords are held in place by a decorative medallion (sakiyā), which can be made from wood, horn, ivory, metal, crystal, or old coins. The edges of the prepared manuscripts are singed with a hot iron, acting to remove stray fibres, prevent decay, and ward off insects.

All the botanical ingredients used in the making of the manuscript contribute to their preservation, including by deterring insect pests. Re-inking the manuscript from time to time can also contribute to its preservation, as can regular touch and use of the manuscript. Almost all the manuscripts found in Osler Library still have the sharp fragrance of blackening oil around a century after their collection. Regular reading makes the folios turn easily and exposes the manuscript to good ventilation in addition to human touch. Some of the manuscripts found in Osler Library contain many “bookmarks”; strings tied through the holes to mark a specific page of interest. Making several copies from a same manuscript or creating a recovery copy from a decaying manuscript can also be considered a form of conservation, since it preserves the content of the manuscript. Because of this tradition of copying, in Sri Lanka, the decaying of a particular manuscript was not considered a major problem in the pre-modern period. In Sri Lankan culture, texts are considered to be living beings and they are offered respect and worship. Some of the rituals performed as part of this worship, such as fumigation, also aid in the conservation process. Therefore, the science of conservation is integral to the making of the manuscript and toits everyday care.

Traditionally, in Sri Lanka, most palm-leaf manuscripts were kept in temple libraries. Now, many are stored in museums and university libraries. Notably, the University of Peradeniya has a collection of over 4,000 olas. Many medical manuscripts are also kept within families. There are also private collections of olas which have been acquired or bought. There are also several foreign libraries which have collections of olas, including libraries in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. Casey Wood himself dispersed many of the olas he collected, to around 50 libraries in Canada and the United States. Casey Wood’s collection contains several important manuscripts. However, there are copies of all these manuscripts also remaining in Sri Lanka. There are no rare manuscripts found in the collection. This can be explained by the fact that indigenous medical knowledge is closely guarded by the families that possess it. In fact, many medical manuscripts are encoded, so that their contents cannot be understood without “the decoding key” mentioned in another manuscript or access to the verbal tradition intended to accompany it.

How should we approach these manuscripts as sources for the history of medicine? In considering this question, we can take into account both their contents and their physical features. The language of the text can give clues about the date of the text, for example by the loan words it contains. Technologies described in the texts (apparatus and implements) and the methods of diagnosis can also help to date the manuscripts and to understand how medical practice developed over time. The ingredients used in prescription also varied over time and different exotic remedies were introduced into the pharmacopeia at different stages. For example, opium is first mentioned in the Yogaratnākaraya, a large and well-known text composed in the 1530s, of which Casey Wood collected several copies. Similarly, some diseases and disease names can be used to date texts. For example, “parangi” (meaning “Portuguese” or “European”), referring to the disease yaws, which was associated with Portuguese presence in Sri Lanka, also dates a text to after the sixteenth century. This term occurs for the first time in Sri Lankan indigenous medical texts in the Yogaratnākara. The physical features of the manuscripts can also help to understand when the text was composed. For example, some manuscripts use Chinese or Sri Lankan coins as medallions to hold the cords in place. The date of these coins could be used to establish the earliest possible date of composition for the text.

As for the date of composition of medical manuscripts, the earliest, the Sārātha Sangrahaya, in Sanskrit verse, is believed to date from the fourth century CE. After this, there is a long gap, which may have partially explained by invasions from South India which reached their height under the Cholas in the tenth century. As the Sri Lankan chronicles record, these invasionsresulted in the destruction of many manuscripts. The first medical manuscript written in Sinhala is the Yōgārnavaya, which dates from the thirteenth century CE. Also dating from the thirteenth century is the Bhēsajjamanjusā, a unique medical manuscript composed in Pali using a stanza form. This text was written for a monastic audience and this explains the absence of paediatrics and gynaecology in the text. Two Sinhala manuscripts, the Prayōgaratnāvaliya and the Varayōgasāraya can also be dated to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries respectively. The sixteenth-century Yōgaratnākaraya is the first to be written in poetic form in Sinhala. The Sārasankṣēpaya is a Sanskrit work in verse from the same century. The Sinhala works Vaidyacintāmani Bhaisajjya Sangarahaya and Varasārasangrahaya date from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries respectively. Medical works continued to be composed on palm leaf manuscripts after the introduction of paper in the seventeenth century and throughout the colonial period.

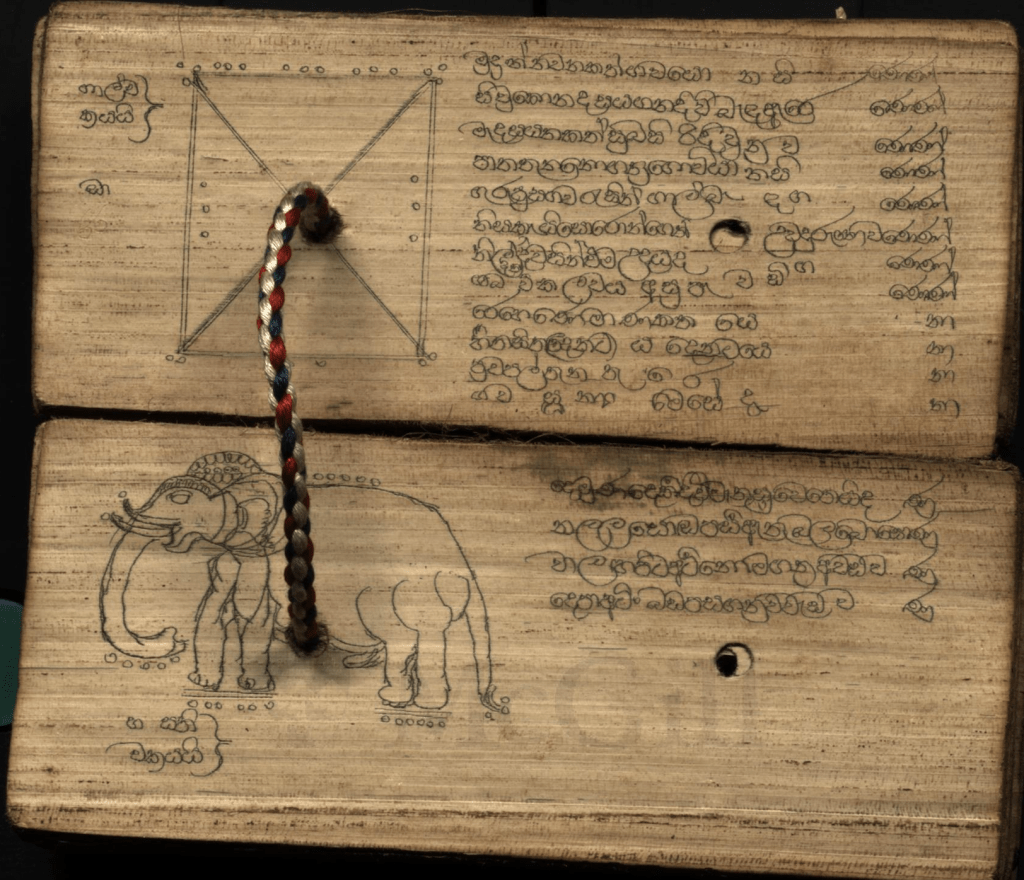

Indigenous medical manuscripts cover a range of topics, including general medicine, fractures and dislocations, snakebites, abscesses and ulcers, eye diseases, catarrh, diarrhoea, children’s diseases, post-partum disorders, fevers, burns, and insanity. Sanni is a special category of disease referring to acute and critical conditions. Other distinct specialism that are related to medicine include: veterinary medicine, focusing specifically on cattle and elephants, crop treatments, therapeutic burning and venesection, astrological prescriptions, ritual healing, formulations (pharmacy) and studies of materia medica, and lexicons including descriptions of the plants, animals, and minerals used in indigenous medicine.

Many of the manuscripts that are held within family lineages do not have names. Often theauthor’s name is not mentioned either since authorship was traditionally considered less important than the contribution to knowledge. Sometimes a date is present in the text. Most medical manuscripts are written in Sinhala, or in Sanskrit using Sinhala characters. Although Casey Wood labelled many of the manuscripts that he collected as being written in Pali-Sinhalese, this is an error, since the Bhēsajjamanjusā is unique in being the only medical work composed in the Pali language. Otherwise, only Buddhist manuscripts are found in the Pali language. Many of the texts contain features that cannot be interpreted without cultural literacy. For example, Casey Wood also mistook some of the images of animals found within the text for zoological images, whereas in fact they are astrological diagrams. The information contained in some manuscripts is encoded: with the key either contained in another manuscript or verbally transmitted as a tool of intellectual property protection. To ensure the survival of the contents of the manuscripts, they were frequently copied, with the copies being stored separately. Because of the respect for the contents and for the manuscripts themselves, they are considered sacred items and treated as living beings. Many of the manuscripts kept within family lineages are treated asfamily treasures, which should not be seen, touched, or read by outsiders. Families with such ancestral heritage will never sell their manuscripts and that may be the reason why there are no rare manuscripts or family treasures are found in Casey Wood collection.

The manuscripts in the McGill library collected by Casey Wood cover a range of topics, including several on Buddhism as well as relating to medicine and healing. During my visit, I was able to identify several manuscripts, as well as to correct some misidentifications. Some manuscripts are in fact made up from of a mixture of folios from several different sources. The reason for this is not clear, perhaps these mixed manuscripts were made up specifically to sell to Casey Wood, who was keen to purchase any medical manuscripts. Many of Wood’s collections were originally without boards or string and he had modern versions made by Kandyan craftsmen. As mentioned already, Casey Wood sent olas to at least 52 other institutions in Canada and the United States as well as to individuals, such as the chairman of the Charaka Club in New York. A few of these olas can now be traced from manuscript catalogues or descriptions and it would be a worthwhile project to track down and identify the others, based on Casey Wood’s records.

As for the content of the manuscripts Casey Wood collected, some are classic texts. A complete copy of the Yōgaratnākaraya is present in the Osler collection and there are fragments of the text in Rare Books. This text was also one that Wood sent to other institutions. The collection also includes compendia written in the recent past, including the Ariṣțaaśataka (which was misidentified as the Yōgamālāva) and the Vaidyālankārasangrahaya. The collection also includes manuscripts focused on the preparation of oils, pills, and other forms of medicine, medical handbooks, astrological texts including rituals. As well as the Buddhist manuscripts already mentioned, there is an important Sanskrit text on the art of statue crafting, the Bimbamānavidhi. As already noted, there are also some mixed manuscripts and fragments within the collection. Although there are no rare manuscripts, the collection does contain several important manuscripts, of which there are also some copies in Sri Lanka. Several have also been printed.

Most of the manuscripts are well-preserved and still readable one hundred years after their collection, while only a few are faded or difficult to read. Many of the strings and covers were replaced or provided by Casey Wood. These replacement cords are larger than the original cords and could damage the parts of the manuscript around the hole. Wood attached labels to many of the manuscripts and the majority were correctly described with the help of Dr Nell. Wood attached precise dates to several manuscripts, but these are based on assumptions and cannot be rationally verified. Several of the manuscripts contain diagrams or pictures. The images that Casey Wood assumed to be zoological are in fact astrological images. The animals are used as shapes and it is the dots that surround them, representing the twenty-seven constellations, that are used for making astrological calculations. Other images also used as constellations include depictions of trees and instruments. The geometric shapes found in many of the manuscripts are used as talismans, which can be used for protection. In some manuscripts, specific talismans are prescribed for particular diseases, and in this way, they are related to medicine. In Sri Lankan medicine, rituals and talismans like these are often used for chronic or incurable diseases, which fall within the category of Sanni. A few of the diagrams used in the text are purely decorative, having nothing to do with the content. These diagrams often appear around the hole through which the string is threaded as well as in empty spaces of the manuscript. These diagrams demonstrate the skill of the scribes in the difficult task of writing with the stylus on the Talipot leaves.

Finally, my suggestion is to trace the locations of the other manuscripts originally in the Casey Wood collection, that were sent to various libraries in Canada and the United States. This can be considered an extended objective of this project. An updated catalogue of Casey Wood’s manuscripts could then be produced including information about all the manuscripts available in libraries other than McGill’s. Also, we must make sure that all the manuscripts are scanned,including those other manuscripts available outside of the McGill collection. Even though the manuscripts are the cultural property of Sri Lanka, I am happy to see them well-preserved, to observe the current interventions to protect them, and to become the first reader after decades. My personal opinion is that there is no need to repatriate them, since the collection contains no rare manuscripts, and the contents are being made available to the public in scanned form as a documentary heritage of Sri Lanka. As a researcher working with medical palm-leaf manuscripts for several decades, I have always believed that not the material, but the content is important for the intellectuals as a research source. Nonetheless, I appreciate the effort made by the McGill University and the Canadian Conservation Institute to protect this documentary heritage and their accepting traditional conservation techniques in a comprehensive and receptive manner.

To learn more about Indigenous medicine in Sri Lanka, please visit the Google Arts and Culture site, Hela Weda Mahima: the glory of indigenous medicine. Lastly, my thanks goes to Casey Albert Wood, a great scholar, researcher, traveller and adventurer as well as naturalist, who preserved these manuscripts for us to study.

Further Reading

Alahakoon, Champa N. K. The Division of Labour in the Production of Sri Lankan Palm Leaf Manuscripts.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka, 2012, Vol. 57 (2): 215–28.

Nell, Andreas, “Ceylon (Sinhalese) olas or book manuscripts on early medicine and how they were made,” Annals of Medical History, 1928, Vol. 10 (3):293-296.